4月1日《经济学人》周报封面即社论区(Leaders)精选文章:《如何应对全球稻米危机》(How to fix the global rice crisis)。

“民以食为天”语出《孟子·公孙丑上》,强调:人民的生命福祉和国家的繁荣昌盛都离不开充足的食物供应。

How to fix the global rice crisis

如何应对全球稻米危机

The world’s most important crop is fuelling climate change and diabetes

这一世界上最重要的作物正在加重气候变化和糖尿病问题

The green revolution was one of the greatest feats of human ingenuity. By promoting higher-yielding varieties of wheat and, especially, rice, plant-breeders in India, Mexico and the Philippines helped China emerge from a famine and India avoid one. From 1965 to 1995 Asia’s rice yields doubled and its poverty almost halved, even as its population soared.

绿色革命是人类创造力的最伟大壮举之一。通过推广高产品种,如小麦,特别是水稻,印度、墨西哥和菲律宾的植物育种者帮助中国摆脱了饥荒(译者的疑惑:中国何时摆脱饥荒,是得益于印度、墨西哥和菲律宾的植物育种者?坦白说,译者孤陋寡闻,此闻所未闻。袁隆平爷爷,您在哪里?),帮助印度避免了饥荒。从1965年到1995年,亚洲的水稻产量翻了一番,贫困人口几乎减少了一半——尽管亚洲人口激增。

《经济学人》2023年3月28日文章配图:亚洲农业与全球稻米危机:稻米养活了超过一半的世界人口,但是,它也加重了糖尿病和气候变化问题。

Asia’s vast rice market is a legacy of that triumph. The starchy grain is the main source of sustenance for over half the world’s population. Asians produce over 90% of rice and get more than a quarter of their calories from it. And demand for the crop is projected to soar, on the back of population growth in Asia and Africa, another big rice consumer. By one estimate, the world will need to produce almost a third more rice by 2050. Yet that looks increasingly hard—and in some ways undesirable.

亚洲巨大的大米市场是这场胜利的遗产。淀粉质谷物是世界上一半以上人口的主要生计来源。亚洲人生产超过90%的大米,并从中获得超过四分之一的卡路里。由于亚洲和非洲(另一个大米消费大户)的人口增长,对大米的需求预计将飙升。据估计,到2050年,世界将需要多生产近三分之一的大米。但这看起来越来越难,且在某些方面是不可取的。

Rice production is spluttering. Yields have increased by less than 1% a year over the past decade, much less than in the previous one. The greatest slowdowns were in South-East Asia, where Indonesia and the Philippines—together, home to 400m people—are already big importers. This has many explanations. Urbanisation and industrialisation have made labour and farmland scarcer. Excessive use of pesticides, fertiliser and irrigation have poisoned and depleted soils and groundwater. But the biggest reason may be global warming.

水稻产量正在锐减。在过去十年中,产量每年增长不到1%,远低于前十年。最严重的放缓出现在东南亚,印尼和菲律宾——总共有4亿人口——已经是进口大国。这有很多解释。城市化和工业化使劳动力和农田变得更加稀缺。过度使用杀虫剂、化肥和灌溉已经毒害和耗尽了土壤和地下水。但最大的原因可能是全球变暖。

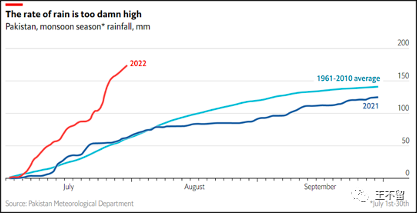

Rice is particularly susceptible to extreme conditions and is often grown in places where they are increasingly evident. Patchy monsoon rains and drought last year in India, the world’s biggest rice exporter, led to a reduced harvest and an export ban. Devastating floods in Pakistan, the fourth-biggest exporter, wiped out 15% of its rice harvest. Rising sea-levels are causing salt to seep into the Mekong Delta, Vietnam’s “rice bowl”.

水稻特别容易受到极端条件的影响,通常种植在极端条件越来越明显的地方。印度是世界上最大的大米出口国,去年的季风降雨分布不均和干旱导致了收成减少和出口禁令。巴基斯坦是世界第四大大米出口国,该国遭受的洪灾摧毁了15%的大米收成。海平面上升导致盐渗入越南的“饭碗”——湄公河三角洲。

《经济学人》2022年8月31日文章配图:为什么今年巴基斯坦的洪水泛滥如此严重?气候变迁,使南亚季风越来越难以捉摸。

It gets worse. Rice is not merely a casualty of climate change, but also a contributor to it. By starving soils of oxygen, paddy cultivation encourages methane-emitting bacteria. It is a bigger source of greenhouse gas than any foodstuff except beef. Its emissions footprint is similar to that of aviation. If you count the conversion of forestland for rice paddy—the fate of much of Madagascar’s rainforest—that footprint is even bigger.

情况变得更糟。稻米不仅是气候变化的牺牲品,也是气候变化的促成者。通过使土壤缺氧,水稻种植会助长甲烷排放菌。除牛肉以外,它是比任何食品都更大的温室气体来源。其排放足迹与航空相似。如果算上将林地转变为稻田——马达加斯加大部分雨林的命运——这个足迹甚至更大。

配图说明:这是中国“绿发会”国际部在2021年8月21日收到的一篇报道中的插图。

Mongabay(蒙加贝)是一家专门提供自然环境新闻资讯的门户网站。这篇特别报道的核心内容:马达加斯加是世界上生物多样性最为丰富的国家之一,目前正面临气候变化带来的饥荒问题——马达加斯加大危机。而马达加斯加大危机,反过来更加重了该国的环境问题。

This amounts to an insidious feedback loop and, in all, a far more complicated set of problems than the food insecurity that spurred the green revolution. Indeed, eating too much rice turns out to be bad for people as well as the climate. White rice is more fattening than bread or maize, and is not especially nutritious. In South Asia, rice-heavy diets have been linked to high rates of diabetes and persistent malnutrition.

这相当于一个隐蔽的反馈循环,总而言之,这一系列问题,远比粮食不足促进绿色革命所产生的问题复杂得多的。事实上,吃太多米饭不仅对气候不利,对人也不利。白米饭比面包或玉米更容易使人发胖,而且营养也不是特别丰富。在南亚,以大米为主的饮食习惯与糖尿病和长期营养不良的高发病率有关。

Policymakers need to increase rice yields, then, but more selectively than in the 1960s. In the places most suitable for rice cultivation, such as hot and sticky South-East Asia, faster adoption of new technologies, such as flood-resistant and more nutritious seeds, could provide a big productivity boost. In tandem with improved practices, such as direct seeding of paddy, they could also shorten the growing cycle and reduce the amount of water required, mitigating environmental harm. Farmers have been slow to adopt such improvements, partly because of overgenerous subsidies that shield them from the rice crisis. A better approach would make state support contingent on best practice. By encouraging crop insurance—a good idea in itself—governments could also help reassure farmers as they switch from old ways to new.

因此,政策制定者需要提高水稻产量,但要比20世纪60年代更有选择性。在最适合水稻种植的地方,如炎热潮湿的东南亚,更快地采用新技术,如抗洪水和更有营养的种子,可以大大提高生产能力。与改进的做法(如水稻直播)相结合,还可以缩短生长周期,减少所需水量,减轻对环境的损害。农民在采用这些改良措施方面进展缓慢,部分原因是过于慷慨的补贴使他们免受大米危机的影响。如果采用更好的办法,国家的支持就可以视最佳的做法而定。通过鼓励农作物保险——这本身就是一个好主意——政府还可以帮助农民在新旧方式转换过程中消除疑虑。

《经济学人》2022年11月1日文章配图:烈日炎炎,收成堪忧——使农业适应近期的气候变化,任重道远。

Governments need to nudge producers and consumers away from rice. India and Indonesia are promoting millet, which is more nutritious and uses a lot less water. Scrapping subsidies that favour rice over other crops would make such efforts more effective. India, for example, procures rice from farmers, often at above-market rates, then distributes it as food aid. It should make its interventions more crop-agnostic, by replacing subsidies and free rice with income support for farmers and cash transfers for the poor. That would encourage farmers to choose the best crop for their local conditions—much of India’s agricultural north-west would switch from rice to wheat overnight. Poor Indians would be free to choose a more balanced diet. Thereby, it would correct a market skewed towards environmental damage and poor health.

政府需要鼓励生产者和消费者远离大米。印度和印尼正在推广小米,小米更有营养,用水也少得多。取消对水稻的补贴将使这些努力更加有效。例如,印度经常以高于市场的价格从农民那里采购大米,然后作为粮食援助分发。这应该使其干预措施更加不受作物的影响,用对农民的收入支持和对穷人的现金转移取代补贴和免费大米。这将鼓励农民根据当地条件选择最好的作物——印度西北部的大部分农业地区将在一夜之间从大米转向小麦。贫穷的印度人可以自由选择更平衡膳食。因此,它将纠正一个向环境破坏和健康不佳倾斜的市场。

《经济学人》2023年3月29日文章配图:亚洲最大的竞赛——印度和印尼——哪一个能够在这个乱世发展更快?

Bringing about such change in Asia and beyond will be far harder than promoting new wonder seeds was. Farmers are almost everywhere a powerful constituency. Yet policymakers should get used to blending complicated economic and technological fixes in this way. Increasingly, it is what fighting climate change will entail. Sorting out the mounting crisis in the world’s most important foodstuff would be a good place to begin.

在亚洲和其它地区带来这样的变化将远比推广新的奇迹种子困难得多。农民几乎在任何地方都是一个强有力的选民群体。然而,政策制定者应该习惯于以这种方式将复杂的经济和技术措施结合起来。这日益成为对抗气候变化的必要条件。解决世界上最重要粮食的日益严重的危机,这将是一个很好的起点。

![数据结构05:树与二叉树[C++][线索二叉树:先序、中序、后序]](https://img-blog.csdnimg.cn/ca1b85fb674a488db9b3a545355a9977.png)