In complex analysis, an essential singularity of a function is a “severe” singularity near which the function exhibits odd behavior.

The category essential singularity is a “left-over” or default group of isolated singularities that are especially unmanageable: by definition they fit into neither of the other two categories of singularity that may be dealt with in some manner – removable singularities and poles. In practice some[who?] include non-isolated singularities too; those do not have a residue.

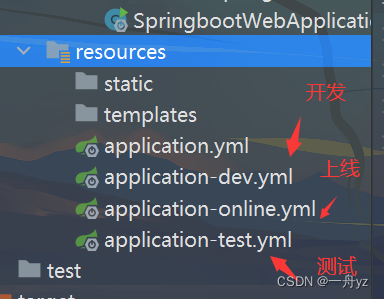

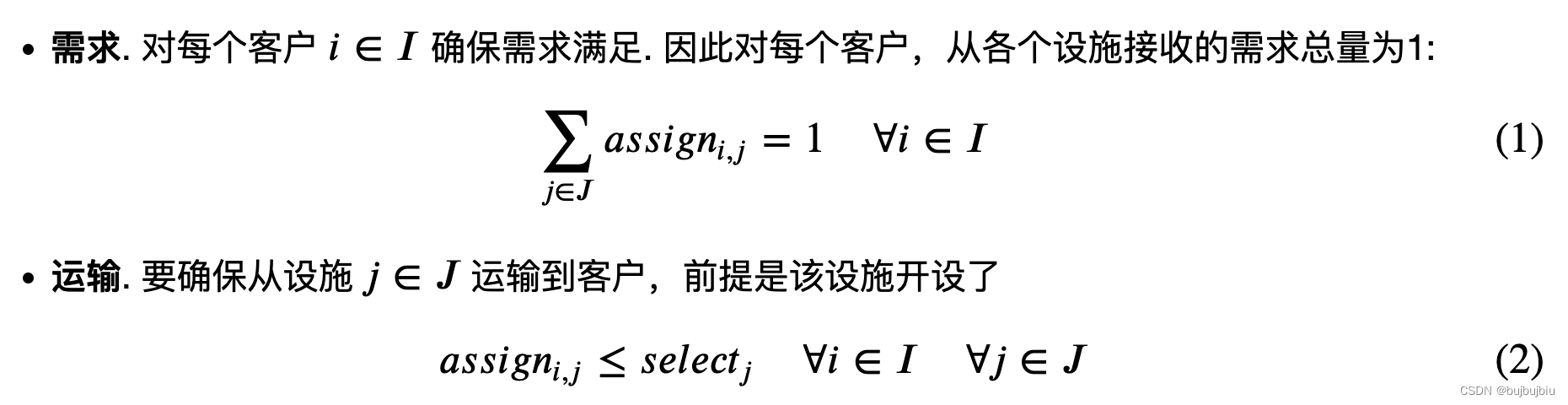

Plot of the function exp(1/z), centered on the essential singularity at z = 0. The hue represents the complex argument, the luminance represents the absolute value. This plot shows how approaching the essential singularity from different directions yields different behaviors (as opposed to a pole, which, approached from any direction, would be uniformly white).

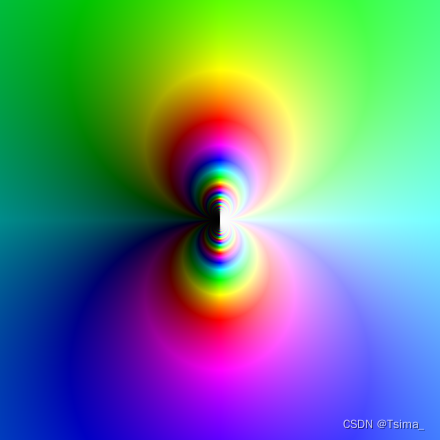

Model illustrating essential singularity of a complex function 6w = exp(1/(6z))

Contents

- 1 Formal description

- 2 Alternative descriptions

1 Formal description

Consider an open subset {\displaystyle U}U of the complex plane {\displaystyle \mathbb {C} }\mathbb {C} . Let {\displaystyle a}a be an element of {\displaystyle U}U, and {\displaystyle f\colon U\setminus {a}\to \mathbb {C} }{\displaystyle f\colon U\setminus {a}\to \mathbb {C} } a holomorphic function. The point {\displaystyle a}a is called an essential singularity of the function {\displaystyle f}f if the singularity is neither a pole nor a removable singularity.

For example, the function {\displaystyle f(z)=e^{1/z}}{\displaystyle f(z)=e^{1/z}} has an essential singularity at {\displaystyle z=0}z=0.

2 Alternative descriptions

Let {\displaystyle ;a;}{\displaystyle ;a;} be a complex number, assume that {\displaystyle f(z)}f(z) is not defined at {\displaystyle ;a;}{\displaystyle ;a;} but is analytic in some region {\displaystyle U}U of the complex plane, and that every open neighbourhood of {\displaystyle a}a has non-empty intersection with {\displaystyle U}U.

If both {\displaystyle \lim {z\to a}f(z)}\lim{z \to a}f(z) and {\displaystyle \lim {z\to a}{\frac {1}{f(z)}}}\lim{z \to a}\frac{1}{f(z)} exist, then {\displaystyle a}a is a removable singularity of both {\displaystyle f}f and {\displaystyle {\frac {1}{f}}}{\displaystyle {\frac {1}{f}}}.

If {\displaystyle \lim {z\to a}f(z)}\lim{z \to a}f(z) exists but {\displaystyle \lim {z\to a}{\frac {1}{f(z)}}}\lim{z \to a}\frac{1}{f(z)} does not exist (in fact {\displaystyle \lim _{z\to a}|1/f(z)|=\infty }{\displaystyle \lim _{z\to a}|1/f(z)|=\infty }), then {\displaystyle a}a is a zero of {\displaystyle f}f and a pole of {\displaystyle {\frac {1}{f}}}{\displaystyle {\frac {1}{f}}}.

Similarly, if {\displaystyle \lim {z\to a}f(z)}\lim{z \to a}f(z) does not exist (in fact {\displaystyle \lim _{z\to a}|f(z)|=\infty }{\displaystyle \lim _{z\to a}|f(z)|=\infty }) but {\displaystyle \lim {z\to a}{\frac {1}{f(z)}}}\lim{z \to a}\frac{1}{f(z)} exists, then {\displaystyle a}a is a pole of {\displaystyle f}f and a zero of {\displaystyle {\frac {1}{f}}}{\displaystyle {\frac {1}{f}}}.

If neither {\displaystyle \lim {z\to a}f(z)}\lim{z \to a}f(z) nor {\displaystyle \lim {z\to a}{\frac {1}{f(z)}}}\lim{z \to a}\frac{1}{f(z)} exists, then {\displaystyle a}a is an essential singularity of both {\displaystyle f}f and {\displaystyle {\frac {1}{f}}}{\displaystyle {\frac {1}{f}}}.

Another way to characterize an essential singularity is that the Laurent series of {\displaystyle f}f at the point {\displaystyle a}a has infinitely many negative degree terms (i.e., the principal part of the Laurent series is an infinite sum). A related definition is that if there is a point {\displaystyle a}a for which no derivative of {\displaystyle f(z)(z-a){n}}f(z)(z-a)n converges to a limit as {\displaystyle z}z tends to {\displaystyle a}a, then {\displaystyle a}a is an essential singularity of {\displaystyle f}f.[1]

On a Riemann sphere with a point at infinity, {\displaystyle \infty _{\mathbb {C} }}{\displaystyle \infty _{\mathbb {C} }}, the function {\displaystyle {f(z)}}{\displaystyle {f(z)}} has an essential singularity at that point if and only if the {\displaystyle {f(1/z)}}{\displaystyle {f(1/z)}} has an essential singularity at 0: i.e. neither {\displaystyle \lim _{z\to 0}{f(1/z)}}{\displaystyle \lim _{z\to 0}{f(1/z)}} nor {\displaystyle \lim _{z\to 0}{\frac {1}{f(1/z)}}}{\displaystyle \lim _{z\to 0}{\frac {1}{f(1/z)}}} exists.[2] The Riemann zeta function on the Riemann sphere has only one essential singularity, at {\displaystyle \infty _{\mathbb {C} }}{\displaystyle \infty _{\mathbb {C} }}.[3]

The behavior of holomorphic functions near their essential singularities is described by the Casorati–Weierstrass theorem and by the considerably stronger Picard’s great theorem. The latter says that in every neighborhood of an essential singularity {\displaystyle a}a, the function {\displaystyle f}f takes on every complex value, except possibly one, infinitely many times. (The exception is necessary; for example, the function {\displaystyle \exp(1/z)}{\displaystyle \exp(1/z)} never takes on the value 0.)