文章目录

- 一、可变参数模板

- 1.1 概念引入

- 1.2 递归函数方式展开参数包

- 1.3 逗号表达式展开参数包

- 1.4 可变参数模板在STL中的应用

- 二、包装器

- 1.1 function

- 1.2 bind

一、可变参数模板

1.1 概念引入

C++11的新特性可变参数模板能够让您创建可以接受可变参数的函数模板和类模板,相比C++98/03,类模版和函数模版中只能含固定数量的模版参数,可变模版参数无疑是一个巨大的改进。

一个基本可变参数的函数模板:

// Args是一个模板参数包,args是一个函数形参参数包

// 声明一个参数包Args...args,这个参数包中可以包含0到任意个模板参数。

template <class ...Args>

void ShowList(Args... args)

{}

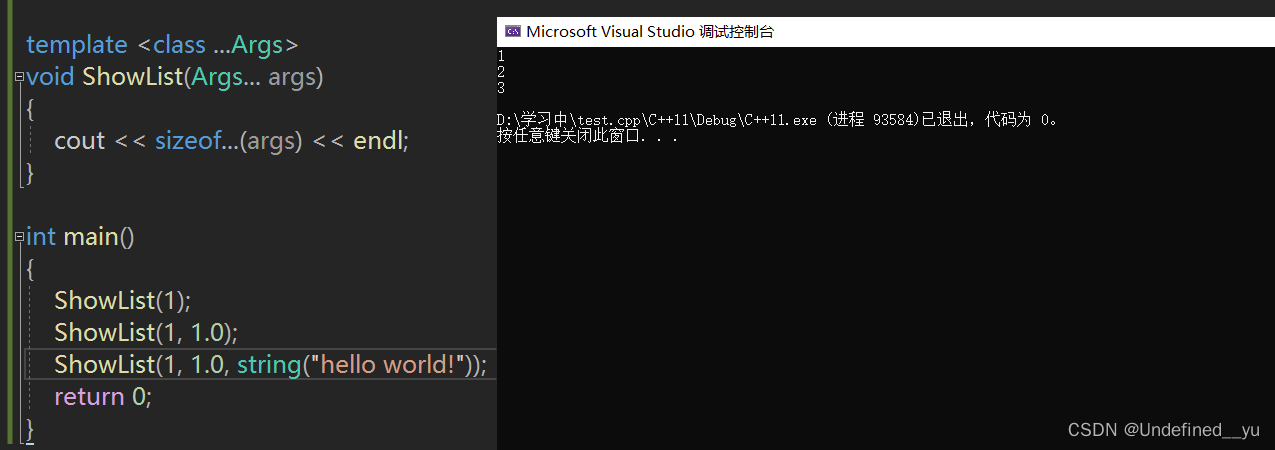

其中sizeof的用法比较特殊,如下:

上面的参数args前面有省略号,所以它就是一个可变模版参数,我们把带省略号的参数称为“参数包”,它里面包含了0到N(N>=0)个模版参数。我们无法直接获取参数包args中的每个参数的,只能通过展开参数包的方式来获取参数包中的每个参数,这是使用可变模版参数的一个主要特点,也是最大的难点,即如何展开可变模版参数。由于语法不支持使用args[i]这样方式获取可变参数,所以我们要用一些奇招来一一获取参数包的值。

1.2 递归函数方式展开参数包

①一般需要提供前向声明、一个参数包的展开函数和一个递归终止函数。

②前向声明有时可省略,递归终止函数可以是0个或n个参数

// 递归终止函数

template <class T>

void ShowList(const T& t)

{

cout << t << endl;

}

// 展开函数

template <class T, class ...Args>

void ShowList(T value, Args... args)

{

cout << value <<" ";

ShowList(args...);

}

int main()

{

ShowList(1);

ShowList(1, 1.0);

ShowList(1, 1.0, string("hello world!"));

return 0;

}

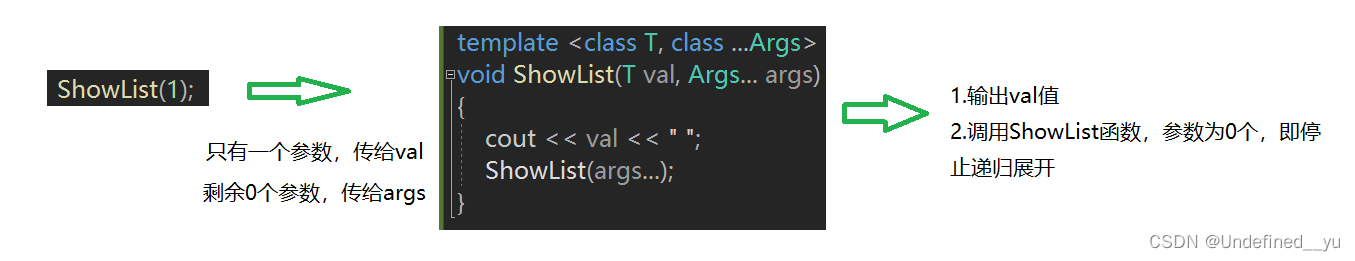

这个不太好理解,大致画了两张图描述递归展开过程:

一个参数:

三个参数:

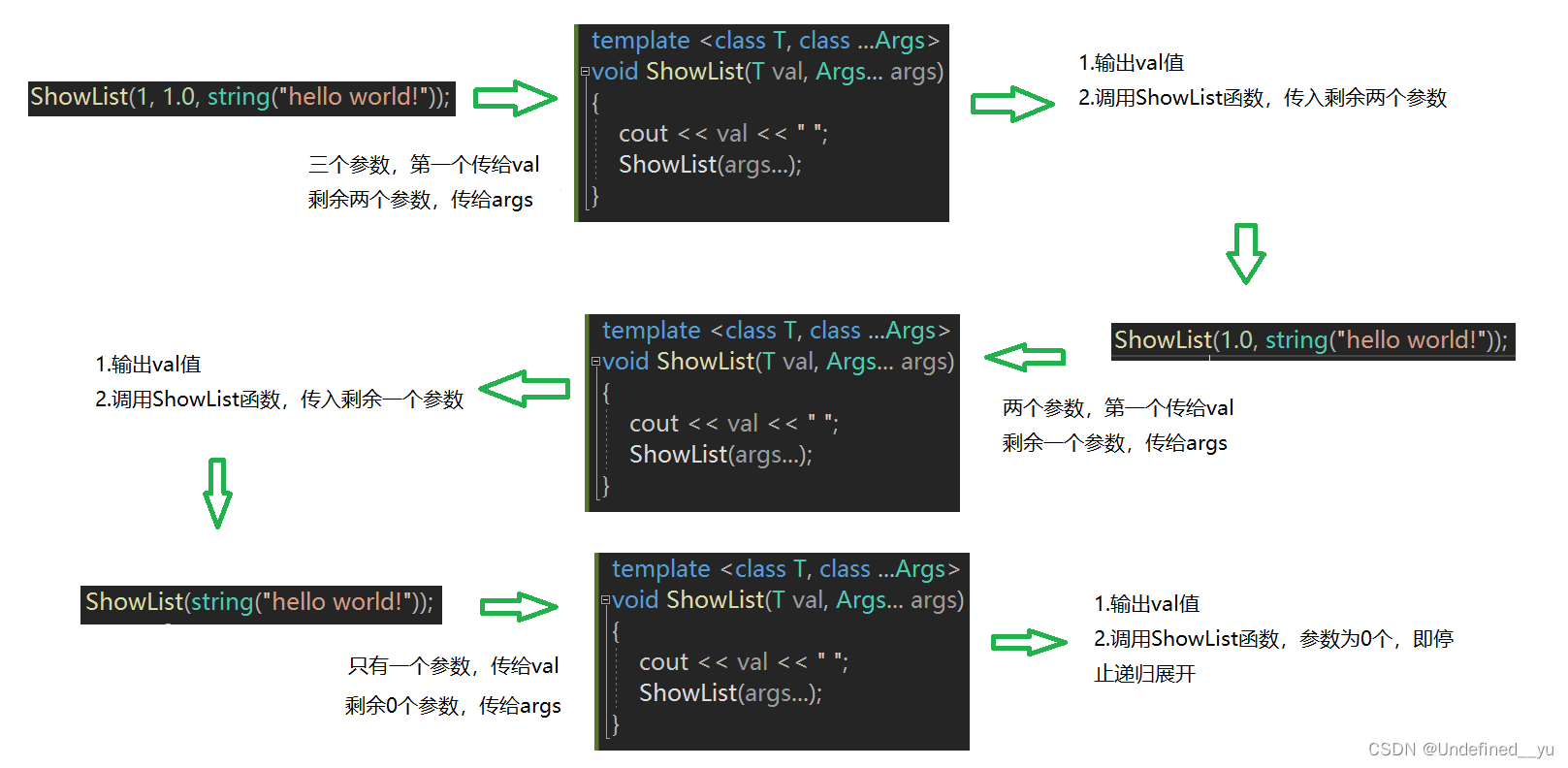

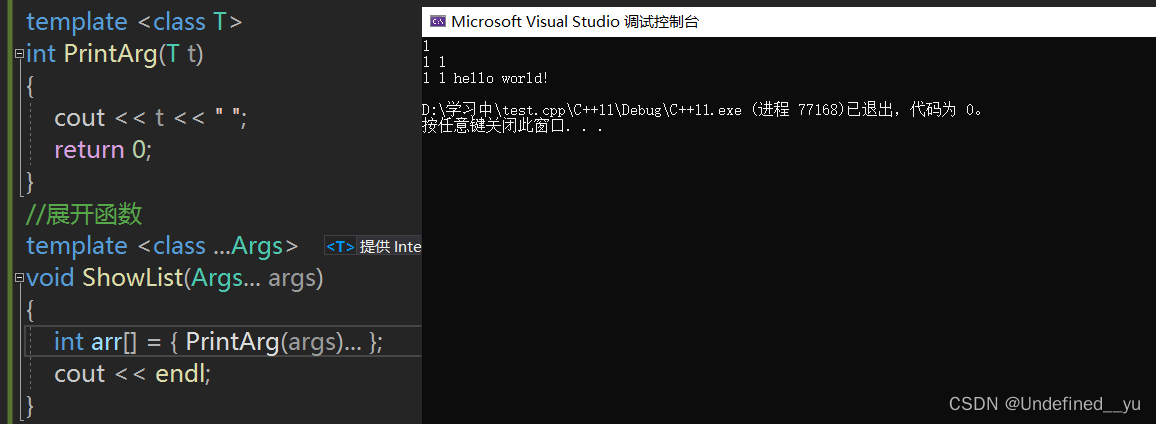

1.3 逗号表达式展开参数包

如下:

template <class T>

void PrintArg(T t)

{

cout << t << " ";

}

//展开函数

template <class ...Args>

void ShowList(Args... args)

{

int arr[] = { (PrintArg(args), 0)... };

cout << endl;

}

int main()

{

ShowList(1);

ShowList(1, 1.0);

ShowList(1,1.0, string("hello world!"));

return 0;

}

这种展开参数包的方式,不需要通过递归终止函数,是直接在expand函数体中展开的, printarg不是一个递归终止函数,只是一个处理参数包中每一个参数的函数。这种就地展开参数包的方式实现的关键是逗号表达式。我们知道逗号表达式会按顺序执行逗号前面的表达式。

expand函数中的逗号表达式:(printarg(args), 0),也是按照这个执行顺序,先执行printarg(args),再得到逗号表达式的结果0。同时还用到了C++11的另外一个特性——初始化列表,通过初始化列表来初始化一个变长数组, {(printarg(args), 0)…}将会展开成((printarg(arg1),0), (printarg(arg2),0), (printarg(arg3),0), etc… ),最终会创建一个元素值都为0的数组int arr[sizeof…(Args)]。由于是逗号表达式,在创建数组的过程中会先执行逗号表达式前面的部分printarg(args)打印出参数,也就是说在构造int数组的过程中就将参数包展开了,这个数组的目的纯粹是为了在数组构造的过程展开参数包

也可以把逗号去掉,改成下面的样子:

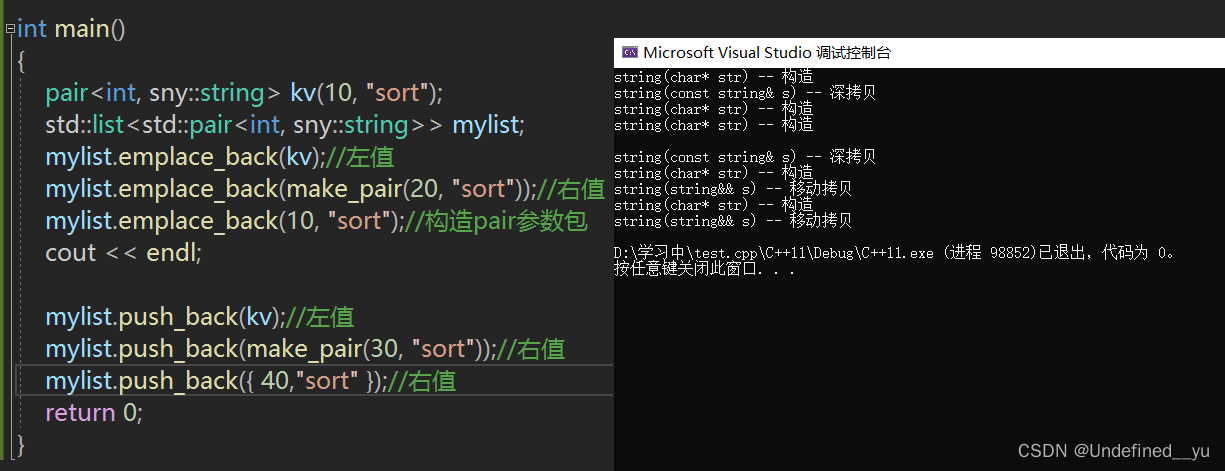

1.4 可变参数模板在STL中的应用

可变参数模板也被应用到了STL的容器中,如下:

meplace_back相较于push_back来说,效率要高那么一点点。

看个例子:

首先要自己实现一个string的类,以便观察过程,如下:

namespace sny

{

class string

{

public:

typedef char* iterator;

iterator begin()

{

return _str;

}

iterator end()

{

return _str + _size;

}

string(const char* str = "")

:_size(strlen(str))

, _capacity(_size)

{

cout << "string(char* str) -- 构造" << endl;

_str = new char[_capacity + 1];

strcpy(_str, str);

}

// s1.swap(s2)

void swap(string& s)

{

::swap(_str, s._str);

::swap(_size, s._size);

::swap(_capacity, s._capacity);

}

// 拷贝构造

string(const string& s)

:_str(nullptr)

{

cout << "string(const string& s) -- 深拷贝" << endl;

/*string tmp(s._str);

swap(tmp);*/

reserve(s._capacity);

strcpy(_str, s._str);

_size = s._size;

_capacity = s._capacity;

}

//移动构造

string(string&& s)

{

cout << "string(string&& s) -- 移动拷贝" << endl;

swap(s);

}

// 移动赋值

string& operator=(string&& s)

{

cout << "string& operator=(string&& s) -- 移动语义" << endl;

swap(s);

return *this;

}

// 赋值重载

string& operator=(const string& s)

{

cout << "string& operator=(string s) -- 深拷贝" << endl;

string tmp(s);

swap(tmp);

return *this;

}

~string()

{

delete[] _str;

_str = nullptr;

}

char& operator[](size_t pos)

{

assert(pos < _size);

return _str[pos];

}

void reserve(size_t n)

{

if (n > _capacity)

{

char* tmp = new char[n + 1];

if (_str)

{

strcpy(tmp, _str);

delete[] _str;

}

_str = tmp;

_capacity = n;

}

}

void push_back(char ch)

{

if (_size >= _capacity)

{

size_t newcapacity = _capacity == 0 ? 4 : _capacity * 2;

reserve(newcapacity);

}

_str[_size] = ch;

++_size;

_str[_size] = '\0';

}

//string operator+=(char ch)

string& operator+=(char ch)

{

push_back(ch);

return *this;

}

const char* c_str() const

{

return _str;

}

private:

char* _str = nullptr;

size_t _size = 0;

size_t _capacity=0; // 不包含最后做标识的\0

};

string to_string(int value)

{

bool flag = true;

if (value < 0)

{

flag = false;

value = 0 - value;

}

sny::string str;

while (value > 0)

{

int x = value % 10;

value /= 10;

str += ('0' + x);

}

if (flag == false)

{

str += '-';

}

std::reverse(str.begin(), str.end());

return str;

}

}

然后进行以下操作:

可以看到,使用emplace_back可以少一次移动构造,原因是在一层层传递的过程中,并没有把参数当做一个对象,而是把它当成一个参数包传至最后一层,然后直接根据其中的值构造对象。

由于移动构造的消耗本来就很小,所以emplace_back并没有比push_back的效率高太多。但是,如果一个容器中没有实现移动构造,那么emplace_back可就高太多了。

二、包装器

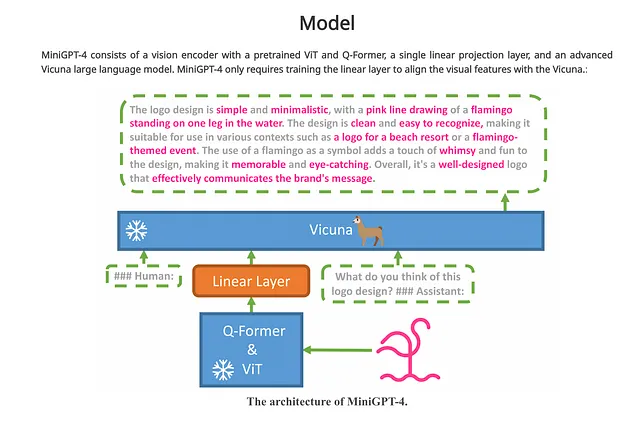

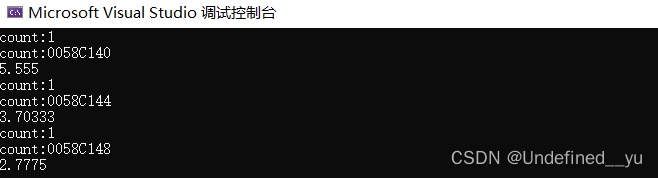

1.1 function

function包装器 也叫作适配器。C++中的function本质是一个类模板,也是一个包装器。

那么我们为什么需要function呢?

先来看这样一个程序:

template<class F, class T>

T useF(F f, T x)

{

static int count = 0;

cout << "count:" << ++count << endl;

cout << "count:" << &count << endl;

return f(x);

}

double f(double i)

{

return i / 2;

}

struct Functor

{

double operator()(double d)

{

return d / 3;

}

};

int main()

{

// 函数名

cout << useF(f, 11.11) << endl;

// 函数对象

cout << useF(Functor(), 11.11) << endl;

// lamber表达式

cout << useF([](double d)->double { return d / 4; }, 11.11) << endl;

return 0;

}

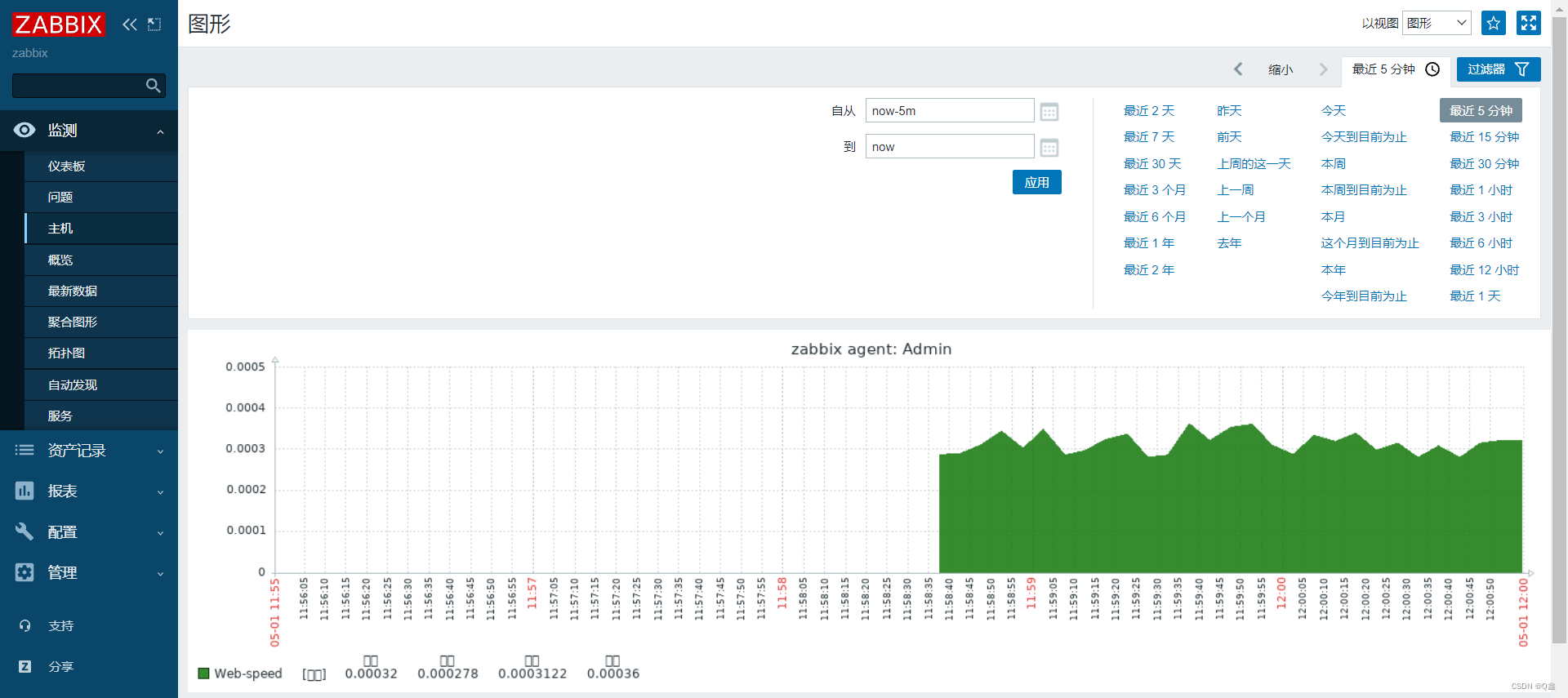

运行结果如下:

上述代码中的func可能是函数名、函数指针、函数对象(仿函数对象),也有可能是lamber表达式对象。所以这些都是可调用的类型!如此丰富的类型,可能会导致模板的效率低下!因为func在实例化的时候,很可能会实例化出很多份。

而包装器就可以很好地解决这个问题。

function包装器格式如下:

std::function在头文件<functional>

// 类模板原型如下

template <class T> function; // undefined

template <class Ret, class... Args>

class function<Ret(Args...)>;

模板参数说明:

Ret: 被调用函数的返回类型

Args…:被调用函数的形参

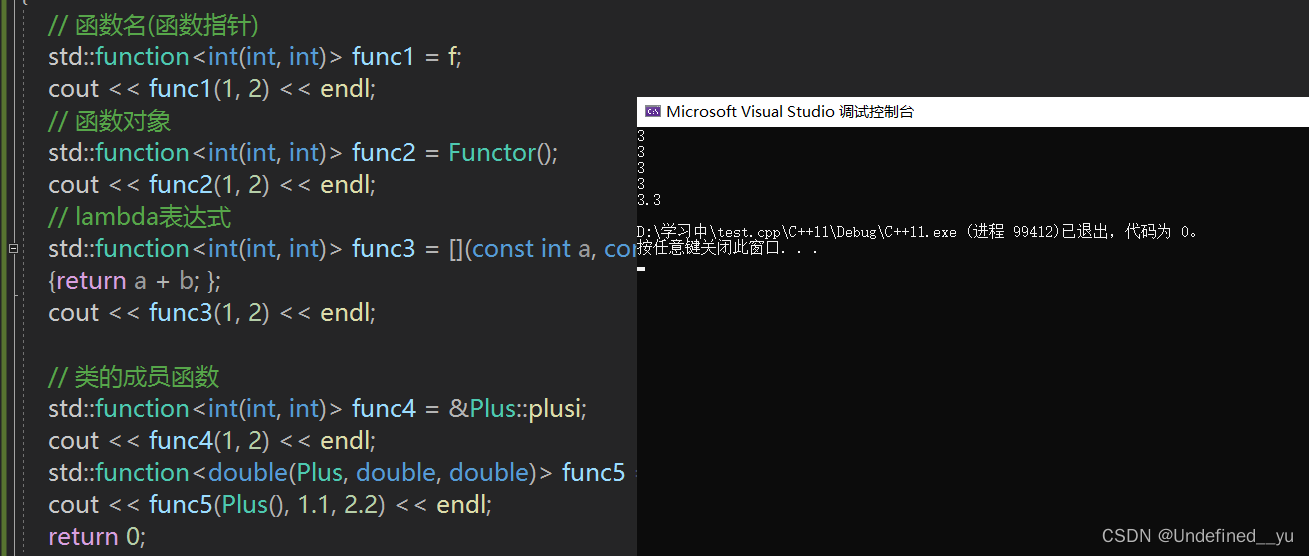

使用举例:

int f(int a, int b)

{

return a + b;

}

struct Functor

{

public:

int operator() (int a, int b)

{

return a + b;

}

};

class Plus

{

public:

static int plusi(int a, int b)

{

return a + b;

}

double plusd(double a, double b)

{

return a + b;

}

};

int main()

{

// 函数名(函数指针)

std::function<int(int, int)> func1 = f;

cout << func1(1, 2) << endl;

// 函数对象

std::function<int(int, int)> func2 = Functor();

cout << func2(1, 2) << endl;

// lambda表达式

std::function<int(int, int)> func3 = [](const int a, const int b)

{return a + b; };

cout << func3(1, 2) << endl;

// 类的成员函数

std::function<int(int, int)> func4 = &Plus::plusi;

cout << func4(1, 2) << endl;

std::function<double(Plus, double, double)> func5 = &Plus::plusd;

cout << func5(Plus(), 1.1, 2.2) << endl;

return 0;

}

注意,包装类的成员函数时,所传的参数应该多一个类型,因为成员函数里还有一个this指针。使用时要传一个匿名对象,而不是取地址!

1.2 bind

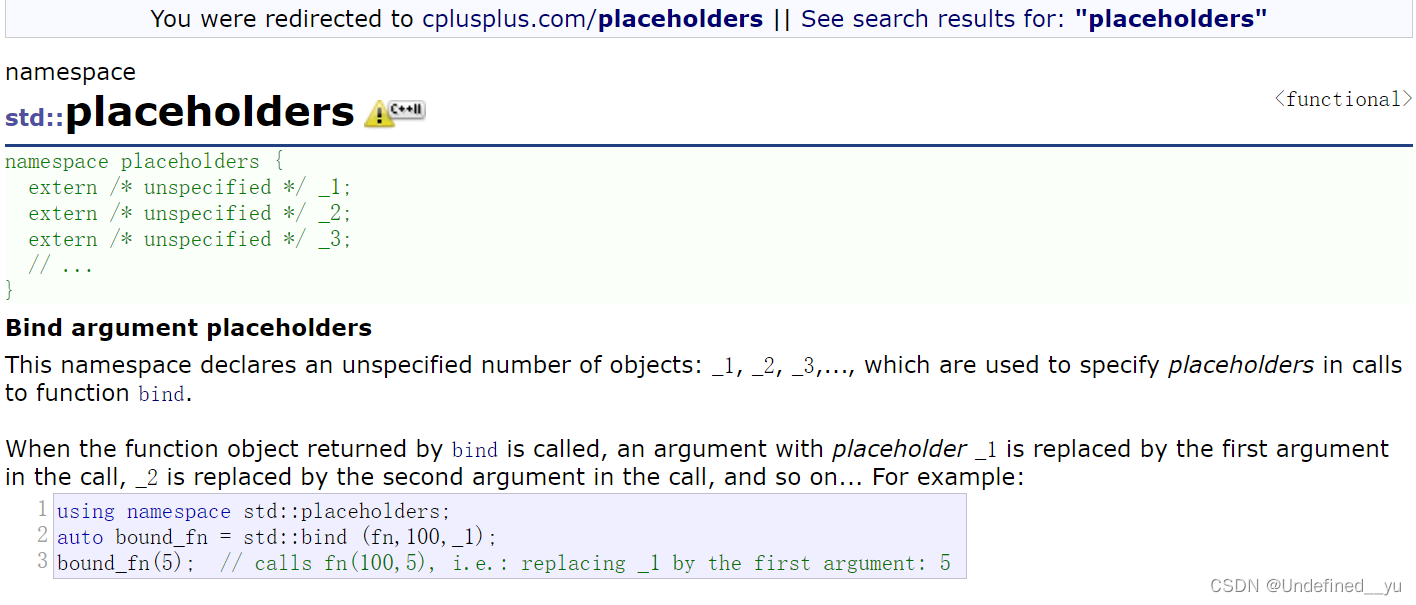

std::bind函数定义在头文件中,是一个函数模板,它就像一个函数包装器(适配器),接受一个可调用对象(callable object),生成一个新的可调用对象来“适应”原对象的参数列表。一般而言,我们用它可以把一个原本接收N个参数的函数fn,通过绑定一些参数,返回一个接收M个(M可以大于N,但这么做没什么意义)参数的新函数。同时,使用std::bind函数还可以实现参数顺序调整等操作。

// 原型如下:

template <class Fn, class... Args>

/* unspecified */ bind (Fn&& fn, Args&&... args);

// with return type (2)

template <class Ret, class Fn, class... Args>

/* unspecified */ bind (Fn&& fn, Args&&... args);

可以将bind函数看作是一个通用的函数适配器,它接受一个可调用对象,生成一个新的可调用对象来“适应”原对象的参数列表。

调用bind的一般形式:auto newCallable = bind(callable,arg_list);

其中,newCallable本身是一个可调用对象,arg_list是一个逗号分隔的参数列表,对应给定的callable的参数。当我们调用newCallable时,newCallable会调用callable,并传给它arg_list中的参数。

arg_list中的参数可能包含形如_n的名字,其中n是一个整数,这些参数是“占位符”,表示newCallable的参数,它们占据了传递给newCallable的参数的“位置”。数值n表示生成的可调用对象中参数的位置:_1为newCallable的第一个参数,_2为第二个参数,以此类推。

如下:

int Plus(int a, int b)

{

return a + b;

}

class Sub

{

public:

int sub(int a, int b)

{

return a - b;

}

};

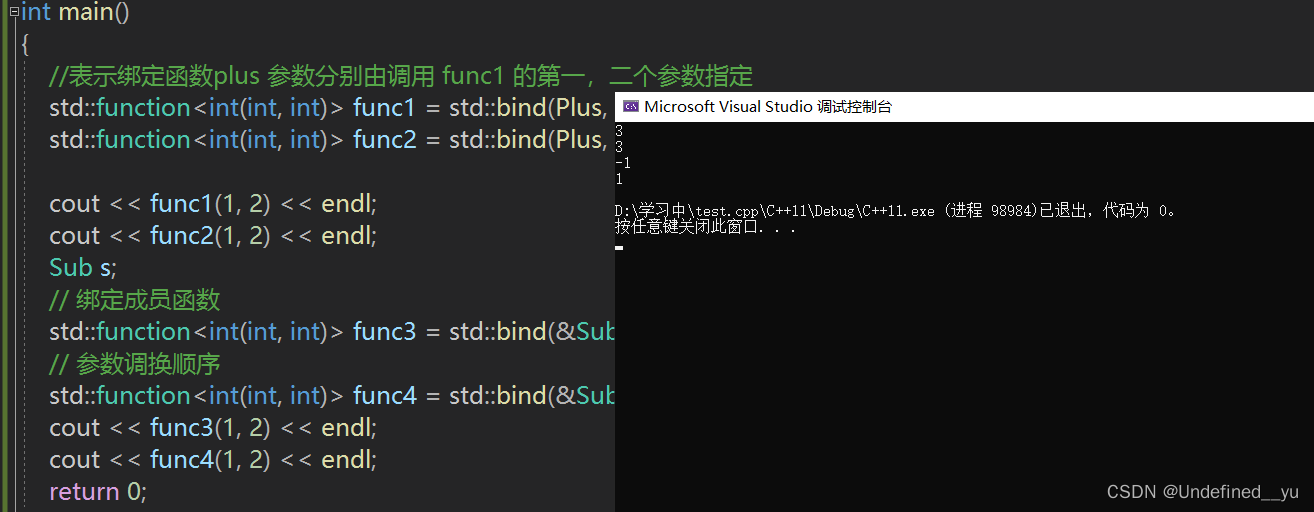

int main()

{

//表示绑定函数plus 参数分别由调用 func1 的第一,二个参数指定

std::function<int(int, int)> func1 = std::bind(Plus, placeholders::_1, placeholders::_2);

std::function<int(int, int)> func2 = std::bind(Plus, placeholders::_1, placeholders::_2);

cout << func1(1, 2) << endl;

cout << func2(1, 2) << endl;

Sub s;

// 绑定成员函数

std::function<int(int, int)> func3 = std::bind(&Sub::sub, s, placeholders::_1, placeholders::_2);

// 参数调换顺序

std::function<int(int, int)> func4 = std::bind(&Sub::sub, s, placeholders::_2, placeholders::_1);

cout << func3(1, 2) << endl;

cout << func4(1, 2) << endl;

return 0;

}

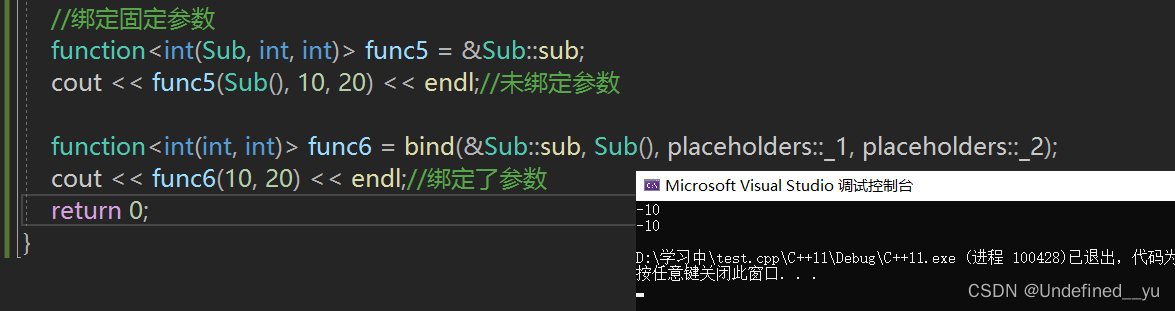

bind也可以用来绑定固定参数,如下:

//绑定固定参数

function<int(Sub, int, int)> func5 = &Sub::sub;

cout << func5(Sub(), 10, 20) << endl;//未绑定参数

function<int(int, int)> func6 = bind(&Sub::sub, Sub(), placeholders::_1, placeholders::_2);

cout << func6(10, 20) << endl;//绑定了参数

可见,它可以用来省略每次使用类的成员函数时,传递的匿名对象。

本篇完,青山不改,绿水长流!