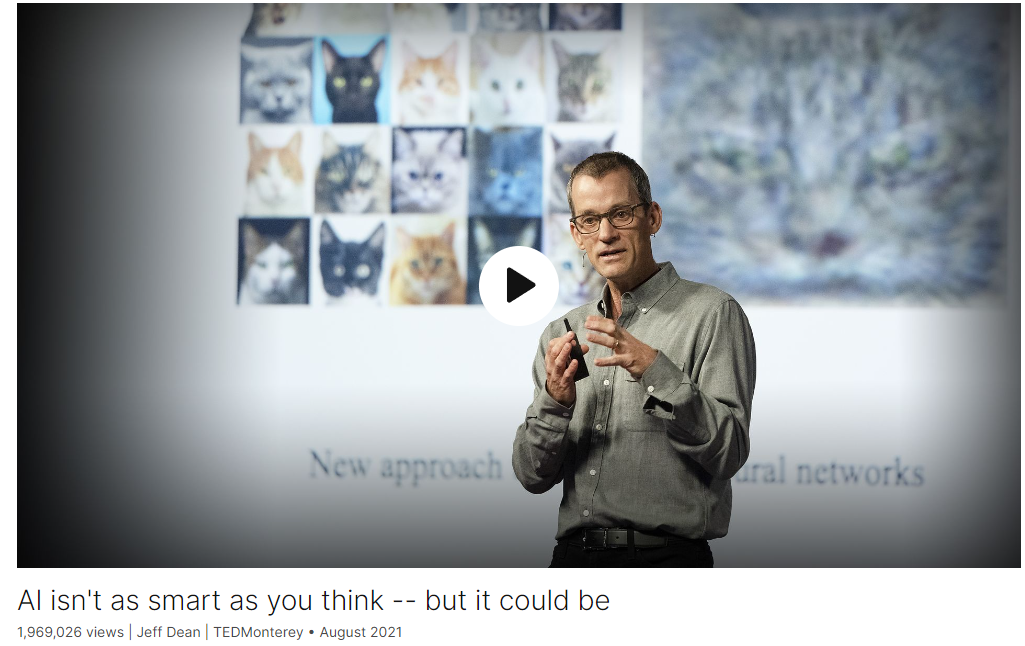

AI isn’t as smart as you think – but it could be

Link: https://www.ted.com/talks/jeff_dean_ai_isn_t_as_smart_as_you_think_but_it_could_be

Speaker: Jeff Dean

Jeffrey Adgate “Jeff” Dean (born July 23, 1968) is an American computer scientist and software engineer. Since 2018, he has been the lead of Google AI.[1] He was appointed Alphabet’s chief scientist in 2023 after a reorganization of Alphabet’s AI focused groups.[2]

Date: August 2021

文章目录

- AI isn't as smart as you think -- but it could be

- Introduction

- Vocabulary

- Transcript

- Q&A with Chris Anderson

- Summary

- 后记

Introduction

What is AI, really? Jeff Dean, the head of Google’s AI efforts, explains the underlying technology that enables artificial intelligence to do all sorts of things, from understanding language to diagnosing disease – and presents a roadmap for building better, more responsible systems that have a deeper understanding of the world. (Followed by a Q&A with head of TED Chris Anderson)

Vocabulary

wedge into:挤进

when we were all wedged into a tiny office space 当我们都挤在一个狭小的办公室里

emulate:美 [ˈemjuleɪt] 模仿,仿效

a series of interconnected artificial neurons that loosely emulate the properties of your real neurons. 一系列相互连接的人造神经元,松散地模拟了真实神经元的特性。

tailored to:合身的,适合的,裁剪的

we also got excited about how we could build hardware that was better tailored to the kinds of computations neural networks wanted to do. 我们还对如何构建更适合神经网络想要进行的计算类型的硬件感到兴奋。

hone:磨砺,磨练

hydroponic:美 [ˌhaɪdrə’pɒnɪk] 水耕法的, 水栽法的

I’ve been honing my gardening skills, experimenting with vertical hydroponic gardening. 我一直在磨练我的园艺技能,尝试垂直水培园艺。

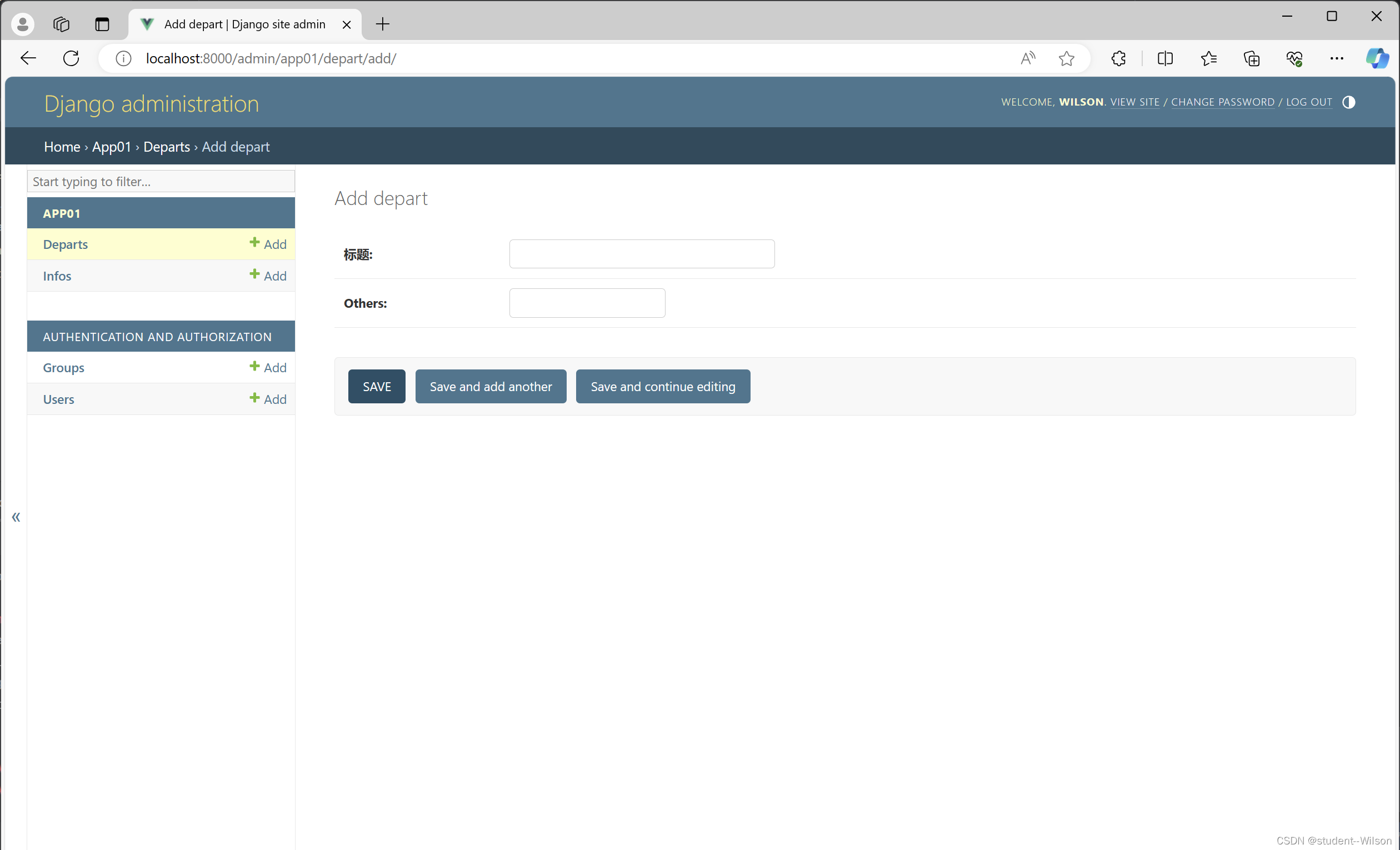

Transcript

Hi, I’m Jeff.

I lead AI Research and Health at Google.

I joined Google more than 20 years ago,

when we were all wedged

into a tiny office space,

above what’s now a T-Mobile store

in downtown Palo Alto.

I’ve seen a lot of computing

transformations in that time,

and in the last decade, we’ve seen AI

be able to do tremendous things.

But we’re still doing it

all wrong in many ways.

That’s what I want

to talk to you about today.

But first, let’s talk

about what AI can do.

So in the last decade,

we’ve seen tremendous progress

in how AI can help computers see,

understand language,

understand speech better than ever before.

Things that we couldn’t do

before, now we can do.

If you think about computer vision alone,

just in the last 10 years,

computers have effectively

developed the ability to see;

10 years ago, they couldn’t see,

now they can see.

You can imagine this has had

a transformative effect

on what we can do with computers.

So let’s look at a couple

of the great applications

enabled by these capabilities.

We can better predict flooding,

keep everyone safe,

using machine learning.

We can translate over 100 languages

so we all can communicate better,

and better predict and diagnose disease,

where everyone gets

the treatment that they need.

So let’s look at two key components

that underlie the progress

in AI systems today.

The first is neural networks,

a breakthrough approach to solving

some of these difficult problems

that has really shone

in the last 15 years.

But they’re not a new idea.

And the second is computational power.

It actually takes a lot

of computational power

to make neural networks

able to really sing,

and in the last 15 years,

we’ve been able to have that,

and that’s partly what’s enabled

all this progress.

But at the same time,

I think we’re doing several things wrong,

and that’s what I want

to talk to you about

at the end of the talk.

First, a bit of a history lesson.

So for decades,

almost since the very

beginning of computing,

people have wanted

to be able to build computers

that could see, understand language,

understand speech.

The earliest approaches

to this, generally,

people were trying to hand-code

all the algorithms

that you need to accomplish

those difficult tasks,

and it just turned out

to not work very well.

But in the last 15 years,

a single approach

unexpectedly advanced all these different

problem spaces all at once:

neural networks.

So neural networks are not a new idea.

They’re kind of loosely based

on some of the properties

that are in real neural systems.

And many of the ideas

behind neural networks

have been around since the 1960s and 70s.

A neural network is what it sounds like,

a series of interconnected

artificial neurons

that loosely emulate the properties

of your real neurons.

An individual neuron

in one of these systems

has a set of inputs,

each with an associated weight,

and the output of a neuron

is a function of those inputs

multiplied by those weights.

So pretty simple,

and lots and lots of these work together

to learn complicated things.

So how do we actually learn

in a neural network?

It turns out the learning process

consists of repeatedly making

tiny little adjustments

to the weight values,

strengthening the influence

of some things,

weakening the influence of others.

By driving the overall system

towards desired behaviors,

these systems can be trained

to do really complicated things,

like translate

from one language to another,

detect what kind

of objects are in a photo,

all kinds of complicated things.

I first got interested in neural networks

when I took a class on them

as an undergraduate in 1990.

At that time,

neural networks showed

impressive results on tiny problems,

but they really couldn’t scale to do

real-world important tasks.

But I was super excited.

(Laughter)

I felt maybe we just needed

more compute power.

And the University of Minnesota

had a 32-processor machine.

I thought, "With more compute power,

boy, we could really make

neural networks really sing."

So I decided to do a senior thesis

on parallel training of neural networks,

the idea of using processors in a computer

or in a computer system

to all work toward the same task,

that of training neural networks.

32 processors, wow,

we’ve got to be able

to do great things with this.

But I was wrong.

Turns out we needed about a million times

as much computational power

as we had in 1990

before we could actually get

neural networks to do impressive things.

But starting around 2005,

thanks to the computing progress

of Moore’s law,

we actually started to have

that much computing power,

and researchers in a few universities

around the world started to see success

in using neural networks for a wide

variety of different kinds of tasks.

I and a few others at Google

heard about some of these successes,

and we decided to start a project

to train very large neural networks.

One system that we trained,

we trained with 10 million

randomly selected frames

from YouTube videos.

The system developed the capability

to recognize all kinds

of different objects.

And it being YouTube, of course,

it developed the ability

to recognize cats.

YouTube is full of cats.

(Laughter)

But what made that so remarkable

is that the system was never told

what a cat was.

So using just patterns in data,

the system honed in on the concept

of a cat all on its own.

All of this occurred at the beginning

of a decade-long string of successes,

of using neural networks

for a huge variety of tasks,

at Google and elsewhere.

Many of the things you use every day,

things like better speech

recognition for your phone,

improved understanding

of queries and documents

for better search quality,

better understanding of geographic

information to improve maps,

and so on.

Around that time,

we also got excited about how we could

build hardware that was better tailored

to the kinds of computations

neural networks wanted to do.

Neural network computations

have two special properties.

The first is they’re very tolerant

of reduced precision.

Couple of significant digits,

you don’t need six or seven.

And the second is that all the

algorithms are generally composed

of different sequences

of matrix and vector operations.

So if you can build a computer

that is really good at low-precision

matrix and vector operations

but can’t do much else,

that’s going to be great

for neural-network computation,

even though you can’t use it

for a lot of other things.

And if you build such things,

people will find amazing uses for them.

This is the first one we built, TPU v1.

“TPU” stands for Tensor Processing Unit.

These have been used for many years

behind every Google search,

for translation,

in the DeepMind AlphaGo matches,

so Lee Sedol and Ke Jie

maybe didn’t realize,

but they were competing

against racks of TPU cards.

And we’ve built a bunch

of subsequent versions of TPUs

that are even better and more exciting.

But despite all these successes,

I think we’re still doing

many things wrong,

and I’ll tell you about three

key things we’re doing wrong,

and how we’ll fix them.

The first is that most

neural networks today

are trained to do one thing,

and one thing only.

You train it for a particular task

that you might care deeply about,

but it’s a pretty heavyweight activity.

You need to curate a data set,

you need to decide

what network architecture you’ll use

for this problem,

you need to initialize the weights

with random values,

apply lots of computation

to make adjustments to the weights.

And at the end, if you’re lucky,

you end up with a model

that is really good

at that task you care about.

But if you do this over and over,

you end up with thousands

of separate models,

each perhaps very capable,

but separate for all the different

tasks you care about.

But think about how people learn.

In the last year, many of us

have picked up a bunch of new skills.

I’ve been honing my gardening skills,

experimenting with vertical

hydroponic gardening.

To do that, I didn’t need to relearn

everything I already knew about plants.

I was able to know

how to put a plant in a hole,

how to pour water, that plants need sun,

and leverage that

in learning this new skill.

Computers can work

the same way, but they don’t today.

If you train a neural

network from scratch,

it’s effectively like forgetting

your entire education

every time you try to do something new.

That’s crazy, right?

So instead, I think we can

and should be training

multitask models that can do

thousands or millions of different tasks.

Each part of that model would specialize

in different kinds of things.

And then, if we have a model

that can do a thousand things,

and the thousand and first

thing comes along,

we can leverage

the expertise we already have

in the related kinds of things

so that we can more quickly be able

to do this new task,

just like you, if you’re confronted

with some new problem,

you quickly identify

the 17 things you already know

that are going to be helpful

in solving that problem.

Second problem is that most

of our models today

deal with only a single

modality of data –

with images, or text or speech,

but not all of these all at once.

But think about how you

go about the world.

You’re continuously using all your senses

to learn from, react to,

figure out what actions

you want to take in the world.

Makes a lot more sense to do that,

and we can build models in the same way.

We can build models that take in

these different modalities of input data,

text, images, speech,

but then fuse them together,

so that regardless of whether the model

sees the word “leopard,”

sees a video of a leopard

or hears someone say the word “leopard,”

the same response

is triggered inside the model:

the concept of a leopard

can deal with different

kinds of input data,

even nonhuman inputs,

like genetic sequences,

3D clouds of points,

as well as images, text and video.

The third problem

is that today’s models are dense.

There’s a single model,

the model is fully activated

for every task,

for every example

that we want to accomplish,

whether that’s a really simple

or a really complicated thing.

This, too, is unlike

how our own brains work.

Different parts of our brains

are good at different things,

and we’re continuously calling

upon the pieces of them

that are relevant for the task at hand.

For example, nervously watching

a garbage truck

back up towards your car,

the part of your brain that thinks

about Shakespearean sonnets

is probably inactive.

(Laughter)

AI models can work the same way.

Instead of a dense model,

we can have one

that is sparsely activated.

So for particular different tasks,

we call upon different parts of the model.

During training, the model can also learn

which parts are good at which things,

to continuously identify what parts

it wants to call upon

in order to accomplish a new task.

The advantage of this is we can have

a very high-capacity model,

but it’s very efficient,

because we’re only calling

upon the parts that we need

for any given task.

So fixing these three things, I think,

will lead to a more powerful AI system:

instead of thousands of separate models,

train a handful of general-purpose models

that can do thousands

or millions of things.

Instead of dealing with single modalities,

deal with all modalities,

and be able to fuse them together.

And instead of dense models,

use sparse, high-capacity models,

where we call upon the relevant

bits as we need them.

We’ve been building a system

that enables these kinds of approaches,

and we’ve been calling

the system “Pathways.”

So the idea is this model

will be able to do

thousands or millions of different tasks,

and then, we can incrementally

add new tasks,

and it can deal

with all modalities at once,

and then incrementally learn

new tasks as needed

and call upon the relevant

bits of the model

for different examples or tasks.

And we’re pretty excited about this,

we think this is going

to be a step forward

in how we build AI systems.

But I also wanted

to touch on responsible AI.

We clearly need to make sure

that this vision of powerful AI systems

benefits everyone.

These kinds of models raise

important new questions

about how do we build them with fairness,

interpretability, privacy and security,

for all users in mind.

For example, if we’re going

to train these models

on thousands or millions of tasks,

we’ll need to be able to train them

on large amounts of data.

And we need to make sure that data

is thoughtfully collected

and is representative of different

communities and situations

all around the world.

And data concerns are only

one aspect of responsible AI.

We have a lot of work to do here.

So in 2018, Google published

this set of AI principles

by which we think about developing

these kinds of technology.

And these have helped guide us

in how we do research in this space,

how we use AI in our products.

And I think it’s a really helpful

and important framing

for how to think about these deep

and complex questions

about how we should

be using AI in society.

We continue to update these

as we learn more.

Many of these kinds of principles

are active areas of research –

super important area.

Moving from single-purpose systems

that kind of recognize patterns in data

to these kinds of general-purpose

intelligent systems

that have a deeper

understanding of the world

will really enable us to tackle

some of the greatest problems

humanity faces.

For example,

we’ll be able to diagnose more disease;

we’ll be able to engineer better medicines

by infusing these models

with knowledge of chemistry and physics;

we’ll be able to advance

educational systems

by providing more individualized tutoring

to help people learn

in new and better ways;

we’ll be able to tackle

really complicated issues,

like climate change,

and perhaps engineering

of clean energy solutions.

So really, all of these kinds of systems

are going to be requiring

the multidisciplinary expertise

of people all over the world.

So connecting AI

with whatever field you are in,

in order to make progress.

So I’ve seen a lot

of advances in computing,

and how computing, over the past decades,

has really helped millions of people

better understand the world around them.

And AI today has the potential

to help billions of people.

We truly live in exciting times.

Thank you.

(Applause)

Q&A with Chris Anderson

Chris Anderson: Thank you so much.

I want to follow up on a couple things.

This is what I heard.

Most people’s traditional picture of AI

is that computers recognize

a pattern of information,

and with a bit of machine learning,

they can get really good at that,

better than humans.

What you’re saying is those patterns

are no longer the atoms

that AI is working with,

that it’s much richer-layered concepts

that can include all manners

of types of things

that go to make up a leopard, for example.

So what could that lead to?

Give me an example

of when that AI is working,

what do you picture happening in the world

in the next five or 10 years

that excites you?

Jeff Dean: I think

the grand challenge in AI

is how do you generalize

from a set of tasks

you already know how to do

to new tasks,

as easily and effortlessly as possible.

And the current approach of training

separate models for everything

means you need lots of data

about that particular problem,

because you’re effectively trying

to learn everything

about the world

and that problem, from nothing.

But if you can build these systems

that already are infused with how to do

thousands and millions of tasks,

then you can effectively

teach them to do a new thing

with relatively few examples.

So I think that’s the real hope,

that you could then have a system

where you just give it five examples

of something you care about,

and it learns to do that new task.

CA: You can do a form

of self-supervised learning

that is based on remarkably

little seeding.

JD: Yeah, as opposed to needing

10,000 or 100,000 examples

to figure everything in the world out.

CA: Aren’t there kind of terrifying

unintended consequences

possible, from that?

JD: I think it depends

on how you apply these systems.

It’s very clear that AI

can be a powerful system for good,

or if you apply it in ways

that are not so great,

it can be a negative consequence.

So I think that’s why it’s important

to have a set of principles

by which you look at potential uses of AI

and really are careful and thoughtful

about how you consider applications.

CA: One of the things

people worry most about

is that, if AI is so good at learning

from the world as it is,

it’s going to carry forward

into the future

aspects of the world as it is

that actually aren’t right, right now.

And there’s obviously been

a huge controversy about that

recently at Google.

Some of those principles

of AI development,

you’ve been challenged that you’re not

actually holding to them.

Not really interested to hear

about comments on a specific case,

but … are you really committed?

How do we know that you are

committed to these principles?

Is that just PR, or is that real,

at the heart of your day-to-day?

JD: No, that is absolutely real.

Like, we have literally hundreds of people

working on many of these

related research issues,

because many of those

things are research topics

in their own right.

How do you take data from the real world,

that is the world as it is,

not as we would like it to be,

and how do you then use that

to train a machine-learning model

and adapt the data bit of the scene

or augment the data with additional data

so that it can better reflect

the values we want the system to have,

not the values that it sees in the world?

CA: But you work for Google,

Google is funding the research.

How do we know that the main values

that this AI will build

are for the world,

and not, for example, to maximize

the profitability of an ad model?

When you know everything

there is to know about human attention,

you’re going to know so much

about the little wriggly,

weird, dark parts of us.

In your group, are there rules

about how you hold off,

church-state wall

between a sort of commercial push,

“You must do it for this purpose,”

so that you can inspire

your engineers and so forth,

to do this for the world, for all of us.

JD: Yeah, our research group

does collaborate

with a number of groups across Google,

including the Ads group,

the Search group, the Maps group,

so we do have some collaboration,

but also a lot of basic research

that we publish openly.

We’ve published more

than 1,000 papers last year

in different topics,

including the ones you discussed,

about fairness, interpretability

of the machine-learning models,

things that are super important,

and we need to advance

the state of the art in this

in order to continue to make progress

to make sure these models

are developed safely and responsibly.

CA: It feels like we’re at a time

when people are concerned

about the power of the big tech companies,

and it’s almost, if there was ever

a moment to really show the world

that this is being done

to make a better future,

that is actually key to Google’s future,

as well as all of ours.

JD: Indeed.

CA: It’s very good to hear you

come and say that, Jeff.

Thank you so much for coming here to TED.

JD: Thank you.

(Applause)

Summary

Jeff Dean’s speech focuses on the transformative potential of AI, highlighting the significant progress made in the last decade. He discusses the capabilities of AI in various domains, such as computer vision, language understanding, and medical diagnosis. Dean attributes this progress to advancements in neural networks and computational power. However, he acknowledges several shortcomings in current AI systems, including their single-task nature, limited modalities, and dense architecture.

Dean proposes solutions to address these shortcomings, advocating for the development of multitask models capable of handling diverse tasks and modalities. He emphasizes the importance of sparse, high-capacity models that can efficiently activate relevant components for specific tasks. Dean introduces the concept of “Pathways,” a system designed to enable these approaches, which he believes will represent a significant step forward in AI research and development.

In addition to discussing technical advancements, Dean emphasizes the importance of responsible AI, highlighting the need for fairness, interpretability, privacy, and security in AI systems. He outlines Google’s AI principles as a guiding framework for responsible AI development and acknowledges the ongoing research and challenges in this area. Dean concludes his speech by expressing optimism about the potential of AI to address complex societal challenges and the importance of multidisciplinary collaboration in realizing this potential.

后记

2024年4月29日18点23分完成这篇演讲的学习。