接前一篇文章:BCC源码内容概览(4)

本文参考官网中的Contents部分的介绍。

BCC源码根目录的文件,其中一些是同时包含C和Python的单个文件,另一些是.c和.py的成对文件,还有一些是目录。

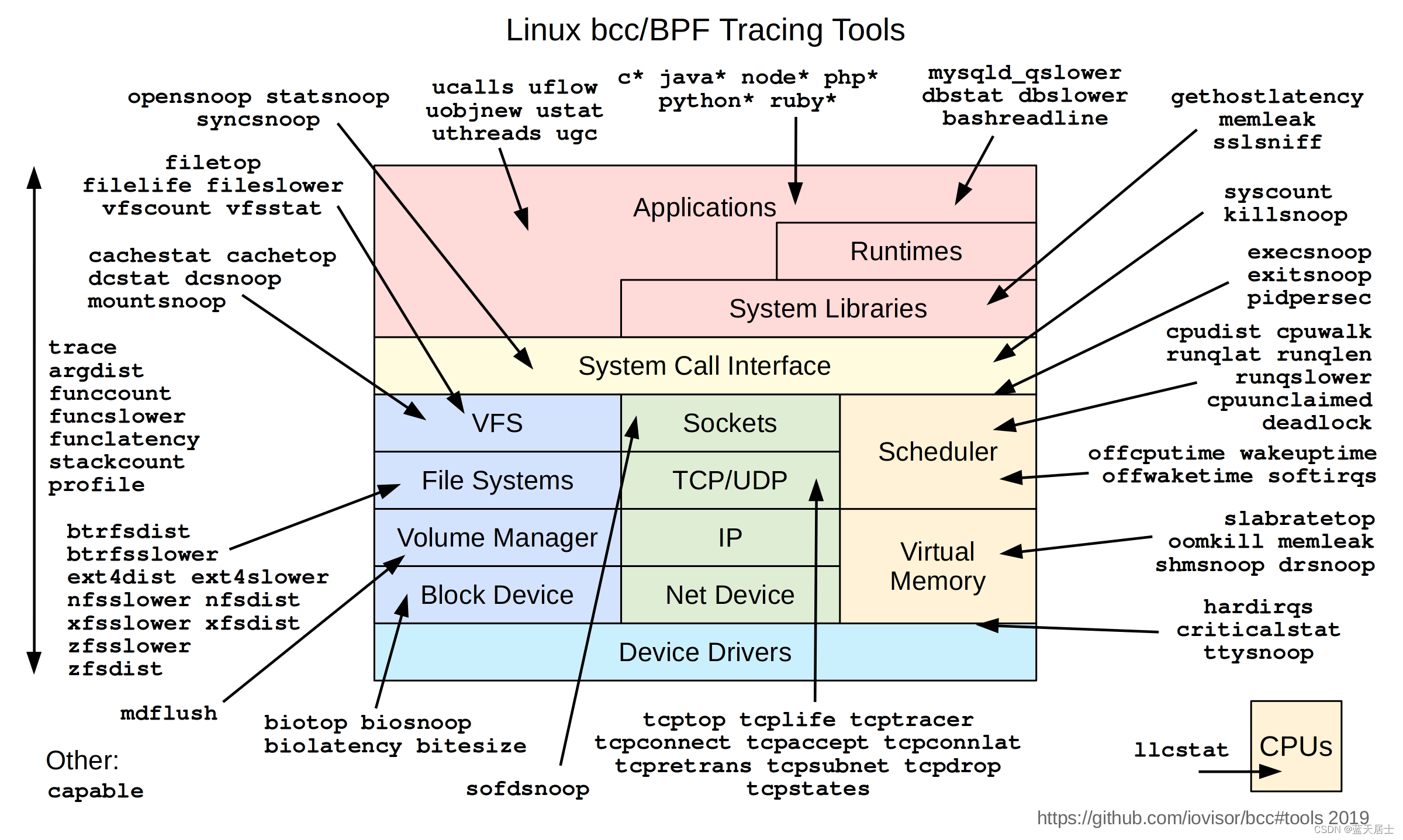

工具(Tools)

eBPF工具概览图如下:

tools目录下的文件:

- tools/argdist

将函数参数值显示为直方图或频率计数。

bcc/tools/argdist_example.txt文件内容如下:

Demonstrations of argdist.

argdist probes functions you specify and collects parameter values into a

histogram or a frequency count. This can be used to understand the distribution

of values a certain parameter takes, filter and print interesting parameters

without attaching a debugger, and obtain general execution statistics on

various functions.

For example, suppose you want to find what allocation sizes are common in

your application:

# ./argdist -p 2420 -c -C 'p:c:malloc(size_t size):size_t:size'

[01:42:29]

p:c:malloc(size_t size):size_t:size

COUNT EVENT

[01:42:30]

p:c:malloc(size_t size):size_t:size

COUNT EVENT

[01:42:31]

p:c:malloc(size_t size):size_t:size

COUNT EVENT

1 size = 16

[01:42:32]

p:c:malloc(size_t size):size_t:size

COUNT EVENT

2 size = 16

[01:42:33]

p:c:malloc(size_t size):size_t:size

COUNT EVENT

3 size = 16

[01:42:34]

p:c:malloc(size_t size):size_t:size

COUNT EVENT

4 size = 16

^C

It seems that the application is allocating blocks of size 16. The COUNT

column contains the number of occurrences of a particular event, and the

EVENT column describes the event. In this case, the "size" parameter was

probed and its value was 16, repeatedly.

Now, suppose you wanted a histogram of buffer sizes passed to the write()

function across the system:

# ./argdist -c -H 'p:c:write(int fd, void *buf, size_t len):size_t:len'

[01:45:22]

p:c:write(int fd, void *buf, size_t len):size_t:len

len : count distribution

0 -> 1 : 0 | |

2 -> 3 : 2 |************* |

4 -> 7 : 0 | |

8 -> 15 : 2 |************* |

16 -> 31 : 0 | |

32 -> 63 : 6 |****************************************|

[01:45:23]

p:c:write(int fd, void *buf, size_t len):size_t:len

len : count distribution

0 -> 1 : 0 | |

2 -> 3 : 11 |*************** |

4 -> 7 : 0 | |

8 -> 15 : 4 |***** |

16 -> 31 : 0 | |

32 -> 63 : 28 |****************************************|

64 -> 127 : 12 |***************** |

[01:45:24]

p:c:write(int fd, void *buf, size_t len):size_t:len

len : count distribution

0 -> 1 : 0 | |

2 -> 3 : 21 |**************** |

4 -> 7 : 0 | |

8 -> 15 : 6 |**** |

16 -> 31 : 0 | |

32 -> 63 : 52 |****************************************|

64 -> 127 : 26 |******************** |

^C

It seems that most writes fall into three buckets: very small writes of 2-3

bytes, medium writes of 32-63 bytes, and larger writes of 64-127 bytes.

But these are writes across the board -- what if you wanted to focus on writes

to STDOUT?

# ./argdist -c -H 'p:c:write(int fd, void *buf, size_t len):size_t:len:fd==1'

[01:47:17]

p:c:write(int fd, void *buf, size_t len):size_t:len:fd==1

len : count distribution

0 -> 1 : 0 | |

2 -> 3 : 0 | |

4 -> 7 : 0 | |

8 -> 15 : 1 |****************************************|

16 -> 31 : 0 | |

32 -> 63 : 1 |****************************************|

[01:47:18]

p:c:write(int fd, void *buf, size_t len):size_t:len:fd==1

len : count distribution

0 -> 1 : 0 | |

2 -> 3 : 0 | |

4 -> 7 : 0 | |

8 -> 15 : 2 |************* |

16 -> 31 : 0 | |

32 -> 63 : 3 |******************** |

64 -> 127 : 6 |****************************************|

[01:47:19]

p:c:write(int fd, void *buf, size_t len):size_t:len:fd==1

len : count distribution

0 -> 1 : 0 | |

2 -> 3 : 0 | |

4 -> 7 : 0 | |

8 -> 15 : 3 |********* |

16 -> 31 : 0 | |

32 -> 63 : 5 |*************** |

64 -> 127 : 13 |****************************************|

^C

The "fd==1" part is a filter that is applied to every invocation of write().

Only if the filter condition is true, the value is recorded.

You can also use argdist to trace kernel functions. For example, suppose you

wanted a histogram of kernel allocation (kmalloc) sizes across the system,

printed twice with 3 second intervals:

# ./argdist -i 3 -n 2 -H 'p::__kmalloc(size_t size):size_t:size'

[01:50:00]

p::__kmalloc(size_t size):size_t:size

size : count distribution

0 -> 1 : 0 | |

2 -> 3 : 0 | |

4 -> 7 : 0 | |

8 -> 15 : 6 |****************************************|

[01:50:03]

p::__kmalloc(size_t size):size_t:size

size : count distribution

0 -> 1 : 0 | |

2 -> 3 : 0 | |

4 -> 7 : 0 | |

8 -> 15 : 22 |****************************************|

16 -> 31 : 0 | |

32 -> 63 : 0 | |

64 -> 127 : 5 |********* |

128 -> 255 : 2 |*** |

Occasionally, numeric information isn't enough and you want to capture strings.

What are the strings printed by puts() across the system?

# ./argdist -i 10 -n 1 -C 'p:c:puts(char *str):char*:str'

[01:53:54]

p:c:puts(char *str):char*:str

COUNT EVENT

2 str = Press ENTER to start.

It looks like the message "Press ENTER to start." was printed twice during the

10 seconds we were tracing.

What about reads? You could trace gets() across the system and print the

strings input by the user (note how "r" is used instead of "p" to attach a

probe to the function's return):

# ./argdist -i 10 -n 1 -C 'r:c:gets():char*:(char*)$retval:$retval!=0'

[02:12:23]

r:c:gets():char*:$retval:$retval!=0

COUNT EVENT

1 (char*)$retval = hi there

3 (char*)$retval = sasha

8 (char*)$retval = hello

Similarly, we could get a histogram of the error codes returned by read():

# ./argdist -i 10 -c 1 -H 'r:c:read()'

[02:15:36]

r:c:read()

retval : count distribution

0 -> 1 : 29 |****************************************|

2 -> 3 : 11 |*************** |

4 -> 7 : 0 | |

8 -> 15 : 3 |**** |

16 -> 31 : 2 |** |

32 -> 63 : 22 |****************************** |

64 -> 127 : 5 |****** |

128 -> 255 : 0 | |

256 -> 511 : 1 |* |

512 -> 1023 : 1 |* |

1024 -> 2047 : 0 | |

2048 -> 4095 : 2 |** |

In return probes, you can also trace the latency of the function (unless it is

recursive) and the parameters it had on entry. For example, we can identify

which processes are performing slow synchronous filesystem reads -- say,

longer than 0.1ms (100,000ns):

# ./argdist -C 'r::__vfs_read():u32:$PID:$latency > 100000'

[01:08:48]

r::__vfs_read():u32:$PID:$latency > 100000

COUNT EVENT

1 $PID = 10457

21 $PID = 2780

[01:08:49]

r::__vfs_read():u32:$PID:$latency > 100000

COUNT EVENT

1 $PID = 10457

21 $PID = 2780

^C

It looks like process 2780 performed 21 slow reads.

You can print the name of the process. This is helpful for short lived processes

and for easier identification of processes response. For example, we can identify

the process using the epoll I/O multiplexing system call

# ./argdist -C 't:syscalls:sys_exit_epoll_wait():char*:$COMM'

[19:57:56]

t:syscalls:sys_exit_epoll_wait():char*:$COMM

COUNT EVENT

4 $COMM = b'node'

[19:57:57]

t:syscalls:sys_exit_epoll_wait():char*:$COMM

COUNT EVENT

2 $COMM = b'open5gs-sgwud'

3 $COMM = b'open5gs-sgwcd'

3 $COMM = b'open5gs-nrfd'

3 $COMM = b'open5gs-udmd'

4 $COMM = b'open5gs-scpd'

Occasionally, entry parameter values are also interesting. For example, you

might be curious how long it takes malloc() to allocate memory -- nanoseconds

per byte allocated. Let's go:

# ./argdist -H 'r:c:malloc(size_t size):u64:$latency/$entry(size);ns per byte' -n 1 -i 10

[01:11:13]

ns per byte : count distribution

0 -> 1 : 0 | |

2 -> 3 : 4 |***************** |

4 -> 7 : 3 |************* |

8 -> 15 : 2 |******** |

16 -> 31 : 1 |**** |

32 -> 63 : 0 | |

64 -> 127 : 7 |******************************* |

128 -> 255 : 1 |**** |

256 -> 511 : 0 | |

512 -> 1023 : 1 |**** |

1024 -> 2047 : 1 |**** |

2048 -> 4095 : 9 |****************************************|

4096 -> 8191 : 1 |**** |

It looks like a tri-modal distribution. Some allocations are extremely cheap,

and take 2-15 nanoseconds per byte. Other allocations are slower, and take

64-127 nanoseconds per byte. And some allocations are slower still, and take

multiple microseconds per byte.

You could also group results by more than one field. For example, __kmalloc

takes an additional flags parameter that describes how to allocate memory:

# ./argdist -c -C 'p::__kmalloc(size_t size, gfp_t flags):gfp_t,size_t:flags,size'

[03:42:29]

p::__kmalloc(size_t size, gfp_t flags):gfp_t,size_t:flags,size

COUNT EVENT

1 flags = 16, size = 152

2 flags = 131280, size = 8

7 flags = 131280, size = 16

[03:42:30]

p::__kmalloc(size_t size, gfp_t flags):gfp_t,size_t:flags,size

COUNT EVENT

1 flags = 16, size = 152

6 flags = 131280, size = 8

19 flags = 131280, size = 16

[03:42:31]

p::__kmalloc(size_t size, gfp_t flags):gfp_t,size_t:flags,size

COUNT EVENT

2 flags = 16, size = 152

10 flags = 131280, size = 8

31 flags = 131280, size = 16

[03:42:32]

p::__kmalloc(size_t size, gfp_t flags):gfp_t,size_t:flags,size

COUNT EVENT

2 flags = 16, size = 152

14 flags = 131280, size = 8

43 flags = 131280, size = 16

^C

The flags value must be expanded by hand, but it's still helpful to eliminate

certain kinds of allocations or visually group them together.

argdist also has basic support for kernel tracepoints. It is sometimes more

convenient to use tracepoints because they are documented and don't vary a lot

between kernel versions. For example, let's trace the net:net_dev_start_xmit

tracepoint and print out the protocol field from the tracepoint structure:

# argdist -C 't:net:net_dev_start_xmit():u16:args->protocol'

[13:01:49]

t:net:net_dev_start_xmit():u16:args->protocol

COUNT EVENT

8 args->protocol = 2048

^C

Note that to discover the format of the net:net_dev_start_xmit tracepoint, you

use the tplist tool (tplist -v net:net_dev_start_xmit).

Occasionally, it is useful to filter certain expressions by string. This is not

trivially supported by BPF, but argdist provides a STRCMP helper you can use in

filter expressions. For example, to get a histogram of latencies opening a

specific file, run this:

# argdist -c -H 'r:c:open(char *file):u64:$latency/1000:STRCMP("test.txt",$entry(file))'

[02:16:38]

[02:16:39]

[02:16:40]

$latency/1000 : count distribution

0 -> 1 : 0 | |

2 -> 3 : 0 | |

4 -> 7 : 0 | |

8 -> 15 : 0 | |

16 -> 31 : 2 |****************************************|

[02:16:41]

$latency/1000 : count distribution

0 -> 1 : 0 | |

2 -> 3 : 0 | |

4 -> 7 : 0 | |

8 -> 15 : 1 |********** |

16 -> 31 : 4 |****************************************|

[02:16:42]

$latency/1000 : count distribution

0 -> 1 : 0 | |

2 -> 3 : 0 | |

4 -> 7 : 0 | |

8 -> 15 : 1 |******** |

16 -> 31 : 5 |****************************************|

[02:16:43]

$latency/1000 : count distribution

0 -> 1 : 0 | |

2 -> 3 : 0 | |

4 -> 7 : 0 | |

8 -> 15 : 1 |******** |

16 -> 31 : 5 |****************************************|

Here's a final example that finds how many write() system calls are performed

by each process on the system:

# argdist -c -C 'p:c:write():int:$PID;write per process' -n 2

[06:47:18]

write by process

COUNT EVENT

3 $PID = 8889

7 $PID = 7615

7 $PID = 2480

[06:47:19]

write by process

COUNT EVENT

9 $PID = 8889

23 $PID = 7615

23 $PID = 2480

USAGE message:

# argdist -h

usage: argdist [-h] [-p PID] [-z STRING_SIZE] [-i INTERVAL] [-n COUNT] [-v]

[-c] [-T TOP] [-H specifier] [-C[specifier] [-I header]

Trace a function and display a summary of its parameter values.

optional arguments:

-h, --help show this help message and exit

-p PID, --pid PID id of the process to trace (optional)

-t TID, --tid TID id of the thread to trace (optional)

-z STRING_SIZE, --string-size STRING_SIZE

maximum string size to read from char* arguments

-i INTERVAL, --interval INTERVAL

output interval, in seconds (default 1 second)

-d DURATION, --duration DURATION

total duration of trace, in seconds

-n COUNT, --number COUNT

number of outputs

-v, --verbose print resulting BPF program code before executing

-c, --cumulative do not clear histograms and freq counts at each interval

-T TOP, --top TOP number of top results to show (not applicable to

histograms)

-H specifier, --histogram specifier

probe specifier to capture histogram of (see examples

below)

-C specifier, --count specifier

probe specifier to capture count of (see examples

below)

-I header, --include header

additional header files to include in the BPF program

as either full path, or relative to current working directory,

or relative to default kernel header search path

Probe specifier syntax:

{p,r,t,u}:{[library],category}:function(signature)[:type[,type...]:expr[,expr...][:filter]][#label]

Where:

p,r,t,u -- probe at function entry, function exit, kernel tracepoint,

or USDT probe

in exit probes: can use $retval, $entry(param), $latency

library -- the library that contains the function

(leave empty for kernel functions)

category -- the category of the kernel tracepoint (e.g. net, sched)

signature -- the function's parameters, as in the C header

type -- the type of the expression to collect (supports multiple)

expr -- the expression to collect (supports multiple)

filter -- the filter that is applied to collected values

label -- the label for this probe in the resulting output

EXAMPLES:

argdist -H 'p::__kmalloc(u64 size):u64:size'

Print a histogram of allocation sizes passed to kmalloc

argdist -p 1005 -C 'p:c:malloc(size_t size):size_t:size:size==16'

Print a frequency count of how many times process 1005 called malloc

with an allocation size of 16 bytes

argdist -C 'r:c:gets():char*:$retval#snooped strings'

Snoop on all strings returned by gets()

argdist -H 'r::__kmalloc(size_t size):u64:$latency/$entry(size)#ns per byte'

Print a histogram of nanoseconds per byte from kmalloc allocations

argdist -C 'p::__kmalloc(size_t size, gfp_t flags):size_t:size:flags&GFP_ATOMIC'

Print frequency count of kmalloc allocation sizes that have GFP_ATOMIC

argdist -p 1005 -C 'p:c:write(int fd):int:fd' -T 5

Print frequency counts of how many times writes were issued to a

particular file descriptor number, in process 1005, but only show

the top 5 busiest fds

argdist -p 1005 -H 'r:c:read()'

Print a histogram of error codes returned by read() in process 1005

argdist -C 'r::__vfs_read():u32:$PID:$latency > 100000'

Print frequency of reads by process where the latency was >0.1ms

argdist -C 'r::__vfs_read():u32:$COMM:$latency > 100000'

Print frequency of reads by process name where the latency was >0.1ms

argdist -H 'r::__vfs_read(void *file, void *buf, size_t count):size_t:$entry(count):$latency > 1000000'

Print a histogram of read sizes that were longer than 1ms

argdist -H \

'p:c:write(int fd, const void *buf, size_t count):size_t:count:fd==1'

Print a histogram of buffer sizes passed to write() across all

processes, where the file descriptor was 1 (STDOUT)

argdist -C 'p:c:fork()#fork calls'

Count fork() calls in libc across all processes

Can also use funccount.py, which is easier and more flexible

argdist -H 't:block:block_rq_complete():u32:args->nr_sector'

Print histogram of number of sectors in completing block I/O requests

argdist -C 't:irq:irq_handler_entry():int:args->irq'

Aggregate interrupts by interrupt request (IRQ)

argdist -C 'u:pthread:pthread_start():u64:arg2' -p 1337

Print frequency of function addresses used as a pthread start function,

relying on the USDT pthread_start probe in process 1337

argdist -H 'p:c:sleep(u32 seconds):u32:seconds' \

-H 'p:c:nanosleep(struct timespec *req):long:req->tv_nsec'

Print histograms of sleep() and nanosleep() parameter values

argdist -p 2780 -z 120 \

-C 'p:c:write(int fd, char* buf, size_t len):char*:buf:fd==1'

Spy on writes to STDOUT performed by process 2780, up to a string size

of 120 characters

argdist -I 'kernel/sched/sched.h' \

-C 'p::__account_cfs_rq_runtime(struct cfs_rq *cfs_rq):s64:cfs_rq->runtime_remaining'

Trace on the cfs scheduling runqueue remaining runtime. The struct cfs_rq is defined

in kernel/sched/sched.h which is in kernel source tree and not in kernel-devel

package. So this command needs to run at the kernel source tree root directory

so that the added header file can be found by the compiler.

argdist -C 'p::do_sys_open(int dfd, const char __user *filename, int flags,

umode_t mode):char*:filename:STRCMP("sample.txt", filename)'

Trace open of the file "sample.txt". It should be noted that 'filename'

passed to the do_sys_open is a char * user pointer. Hence parameter

'filename' should be tagged with __user for kprobes (const char __user

*filename). This information distinguishes if the 'filename' should be

copied from userspace to the bpf stack or from kernel space to the bpf

stack.在笔者电脑上实际运行结果如下:

~/eBPF/BCC/bcc/tools$ sudo ./argdist.py -c -H 'p:c:write(int fd, void *buf, size_t len):size_t:len:fd==1'

[10:23:54]

len : count distribution

0 -> 1 : 0 | |

2 -> 3 : 0 | |

4 -> 7 : 0 | |

8 -> 15 : 1 |****************************************|

[10:23:55]

len : count distribution

0 -> 1 : 0 | |

2 -> 3 : 0 | |

4 -> 7 : 0 | |

8 -> 15 : 2 |******************** |

16 -> 31 : 0 | |

32 -> 63 : 1 |********** |

64 -> 127 : 4 |****************************************|

[10:23:56]

len : count distribution

0 -> 1 : 0 | |

2 -> 3 : 0 | |

4 -> 7 : 0 | |

8 -> 15 : 3 |********** |

16 -> 31 : 0 | |

32 -> 63 : 2 |******* |

64 -> 127 : 11 |****************************************|

[10:23:57]

len : count distribution

0 -> 1 : 0 | |

2 -> 3 : 0 | |

4 -> 7 : 0 | |

8 -> 15 : 4 |******** |

16 -> 31 : 0 | |

32 -> 63 : 3 |****** |

64 -> 127 : 19 |****************************************|

128 -> 255 : 0 | |

256 -> 511 : 1 |** |

512 -> 1023 : 0 | |

1024 -> 2047 : 0 | |

2048 -> 4095 : 0 | |

4096 -> 8191 : 8 |**************** |

- tools/bashreadline

打印系统范围内输入的bash命令。

bcc/tools/bashreadline.txt文件内容如下:

Demonstrations of bashreadline, the Linux eBPF/bcc version.

This prints bash commands from all running bash shells on the system. For

example:

# ./bashreadline

TIME PID COMMAND

05:28:25 21176 ls -l

05:28:28 21176 date

05:28:35 21176 echo hello world

05:28:43 21176 foo this command failed

05:28:45 21176 df -h

05:29:04 3059 echo another shell

05:29:13 21176 echo first shell again

When running the script on Arch Linux, you may need to specify the location

of libreadline.so library:

# ./bashreadline -s /lib/libreadline.so

TIME PID COMMAND

11:17:34 28796 whoami

11:17:41 28796 ps -ef

11:17:51 28796 echo "Hello eBPF!"

The entered command may fail. This is just showing what command lines were

entered interactively for bash to process.

It works by tracing the return of the readline() function using uprobes

(specifically a uretprobe).但是在笔者电脑上实际运行,结果如下:

~/eBPF/BCC/bcc/tools$ sudo ./bashreadline.py

[sudo] penghao 的密码:Traceback (most recent call last):

File "/home/penghao/eBPF/BCC/bcc/tools/./bashreadline.py", line 66, in <module>

b.attach_uretprobe(name=name, sym="readline", fn_name="printret")

File "/usr/lib/python3.11/site-packages/bcc/__init__.py", line 1412, in attach_uretprobe

(path, addr) = BPF._check_path_symbol(name, sym, addr, pid)

^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^

File "/usr/lib/python3.11/site-packages/bcc/__init__.py", line 978, in _check_path_symbol

raise Exception("could not determine address of symbol %s in %s"

Exception: could not determine address of symbol readline in /bin/bash