An Introduction to American Law

本文是 https://www.coursera.org/programs/career-training-for-nevadans-k7yhc/learn/american-law 这门课的学习笔记。

文章目录

- An Introduction to American Law

- Instructors

- Week 05: Criminal Law

- Key Criminal Law Terms

- Supplemental Reading

- Criminal Law: Part 1

- Criminal Law: Part 2

- Criminal Law: Part 3

- Criminal Law: Part 4

- Criminal Law Quiz

- 法律英语

- 后记

Instructors

Anita Allen, Henry R. Silverman Professor of Law and Professor of Philosophy, Penn Law, University of Pennsylvania

Shyam Balganesh, Professor of Law, Penn Law, University of Pennsylvania

Stephen Morse, Ferdinand Wakeman Hubbell Professor of Law; Professor of Psychology and Law in Psychiatry; Associate Director, Center for Neuroscience & Society, Penn Law, University of Pennsylvania

Theodore Ruger, Dean and Bernard G. Segal Professor of Law, Penn Law, University of Pennsylvania

Tess Wilkinson-Ryan, Assistant Professor of Law and Psychology, Penn Law, University of Pennsylvania

Tobias Barrington Wolff, Professor of Law, Penn Law, University of Pennsylvania

Week 05: Criminal Law

In this module, Professor Morse will focus on the basics of criminal law, an area of law so exciting that countless TV shows and movies have been based on it. The major aspects of criminal law will be discussed - why we impose punishment, when we impose the most punishment, and how the state proves a criminal case. Defenses to criminal charges, which are divided into justifications and excuses will also be addressed.

Key Criminal Law Terms

Crime

Behavior that the law makes punishable as a public offense. For more, click here: http://www.law.cornell.edu/wex/crime

Criminal Law

Body of law that defines criminal offenses, regulates the apprehension, charging, and trial of suspected offenders, and fixes punishment for convicted persons. Substantive criminal law defines particular crimes, and procedural law establishes rules for the prosecution of crime. (http://www.merriam-webster.com/) For more, click here: http://www.law.cornell.edu/wex/criminal_law

Criminal Procedure

The set of rules governing the series of proceedings through which the government enforces substantive criminal law. Municipalities, states, and the federal government each have their own criminal codes, defining types of conduct that constitute crimes. For more, click here: http://www.law.cornell.edu/wex/criminal_procedure

Key Terms:

actus reus

The act or omissions that comprise the physical elements of a crime as required by statute. The statutory definition of a crime pairs actus reus with mens rea, the psychological state defining a criminal perpetrator as culpable for having committed a crime. (http://www.law.cornell.edu/wex/actus_reus)

affirmative defense

A defense in which the defendant introduces evidence, which, if found to be credible, will negate criminal or civil liability, even if it is proven that the defendant committed the alleged acts. Self-defense, entrapment, insanity, and necessity are some examples of affirmative defenses. (http://www.law.cornell.edu/wex/affirmative_defense)

American Law Institute Model Penal Code (MPC)

The purpose of the Model Penal Code was to stimulate and assist legislatures in making a major effort to appraise the content of the penal law by a contemporary reasoned judgment—the prohibitions it lays down, the excuses it admits, the sanctions it employs, and the range of the authority that it distributes and confers. Since its promulgation, the Code has played an important part in the widespread revision and codification of the substantive criminal law of the United States. (http://www.ali.org/)

burden of proof

The threshold that a party seeking to prove a fact in court must reach in order to have that fact legally established. For example, in criminal cases, the burden of proving defendant’s guilt is on the prosecution, and they must establish that fact beyond a reasonable doubt. In civil cases, the plaintiff has the burden of proving his case by a preponderance of the evidence. (http://www.law.cornell.edu/wex/burden_of_proof)

excuse

A type of defense that exempts the defendant from liability because of some circumstance, but does not actually condone the result that flowed (at least in part) from the defendant’s actions. In other words, a defendant with a valid excuse will not suffer the usual penalty for his actions, but the law “wishes” that the defendant had acted differently (as compared to a justification). (http://www.law.cornell.edu/wex/excuse)

insanity

A person accused of a crime can acknowledge that they committed the crime, but argue they are not responsible for it because of their mental illness, by pleading “not guilty by reason of insanity.” For more, click here: http://www.law.cornell.edu/wex/insanity_defense

justification

A type of defense that exempts the defendant from liability because the defendant’s actions were justified. In other words, a defendant with a valid justification will not suffer the usual penalty for his actions because in the eyes of the court, the defendant could not have been asked to act any differently in this situation (as compared to excuses). (http://www.law.cornell.edu/wex/justification)

mens rea

Criminal intent. The state of mind indicating culpability which is required by statute as an element of a crime. (http://www.law.cornell.edu/wex/mens_rea) The four mental states, in increasing order of severity, are negligence, recklessness, knowledge, and purpose/intent.

prima facie

Latin for “at first sight.” A prima facie case is the establishment of a legally required rebuttable presumption. It is generally understood as a flexible evidentiary standard that measures the effect of evidence as meeting, or tending to meet, the proponent’s burden of proof on a given issue. In that sense, a prima facie case is a cause of action or defense that is sufficiently established by a party’s evidence to justify a verdict in his or her favor, provided such evidence is not rebutted by the other party. (http://www.law.cornell.edu/wex/prima_facie)

self-defense

The use of force to protect oneself from an attempted injury by another. If justified, self-defense is a defense to a number of crimes and torts involving force, including murder, assault, and battery. (http://www.law.cornell.edu/wex/self-defense)

sentencing

A criminal sentence refers to the formal legal consequences associated with a conviction. Types of sentences include probation, fines, short-term incarceration, suspended sentences, which only take effect if the convict fails to meet certain conditions, payment of restitution to the victim, community service, or drug and alcohol rehabilitation for minor crimes. More serious sentences include long-term incarceration, life-in-prison, or the death penalty in capital murder cases. For more on this, click here: http://www.law.cornell.edu/wex/sentencing

Supplemental Reading

- “Criminal Charges: How Cases Get Started”

- “Steps in a Criminal Case: From Arrest to Appeal”

- Excerpt from Westlaw’s Black Letter Law Outline: Criminal Law

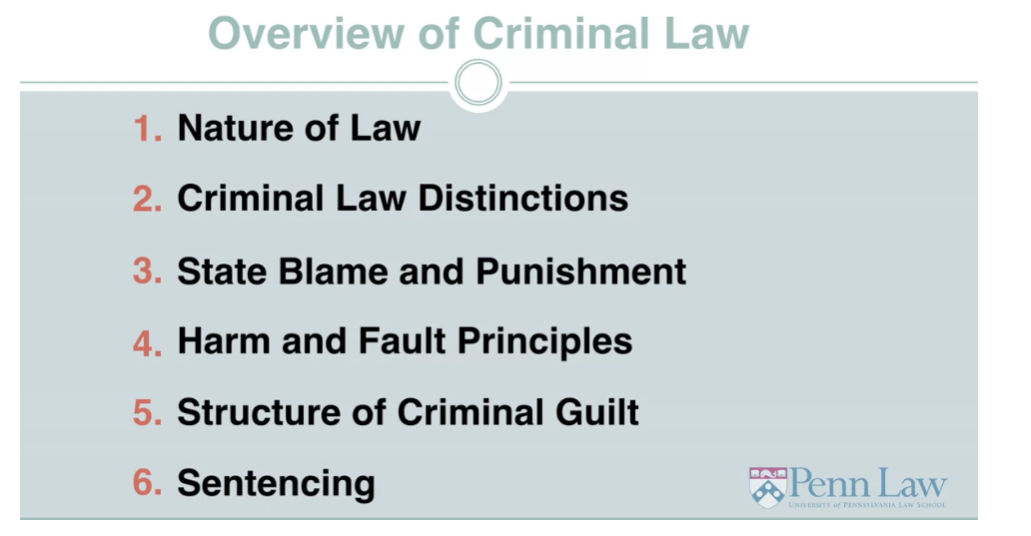

Criminal Law: Part 1

[MUSIC] Hello, my name is Stephen Morse. I’m a lawyer and professor at Penn Law

School, and I’ve been teaching and writing about criminal law for

many decades. I’m also a psychologist and a forensic psychologist, and

I’ve testified in many criminal cases. It is my pleasure to provide this

introduction to criminal law in the United States. Let’s begin. As is well known,

the American political system is federal. The states and

the federal government are independent but related entities and

each has its own legal system. There are essentially 51 sets

of criminal laws, one for each of the 50 states and

the federal government. This lecture will attempt to

provide a general overview, but you should recognize that there

may be substantial variation concerning particulars across jurisdictions. I begin by describing the nature of

law and what is distinctive about criminal law that differentiates

it from civil regulation. Then I address the justifications for state blame and punishment,

which are the touchstones of criminal law. The next section describes the harm and fault principles that guide definition

of so much of the criminal law. Following that, this lecture describes

the structure of criminal guilt, that is, how criminal liability is established. The lecture concludes by

considering sentencing.

I will also try to say what is distinctive

about United States criminal law, but United States criminal law is very

similar in most, but not all respects, to the criminal law of other developed,

post industrial countries. What is distinctive about law and

about criminal law in particular? In this section, I first offer

a simplified picture of what law is, then I turn to what is distinctive

about criminal law in particular. It is difficult to describe what

is distinctive about criminal law, without saying something about what

is distinctive about law as a way of regulating and

ordering our lives together. Consider what kinds of creatures we are. As Aristotle famously observed millenia

ago, we are social creatures, but so are ants and chimps. What is different about us, we human

beings, is that we’re the only creatures on earth that have linguistic abilities,

and are able to be guided by reasons. We have biological predispositions

like the other animals on earth, and these probably set limits. But we are the only creatures

that self consciously, and intentionally, create systems of rules and

institutions to help us order our lives by giving us reasons

to behave one way or another.

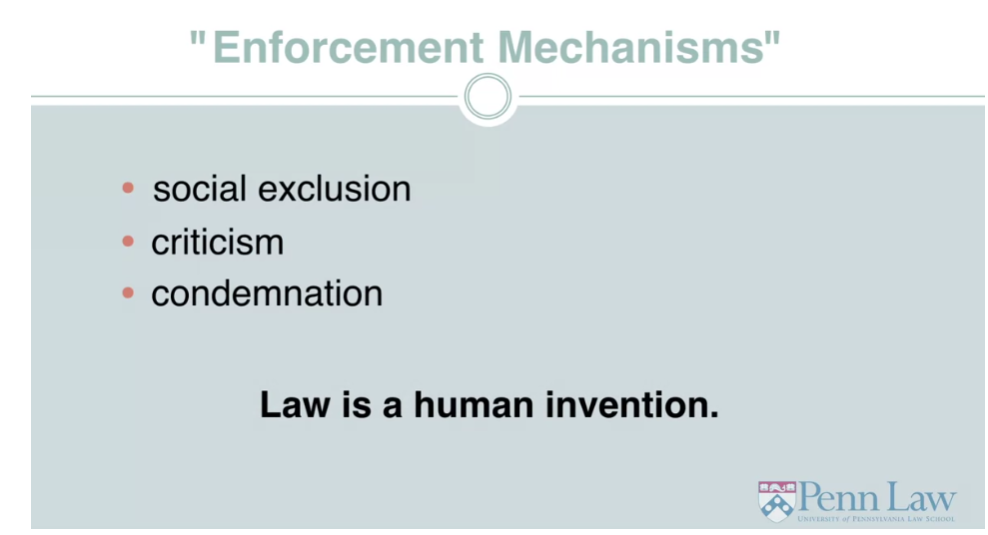

There is great diversity

among human beings and how they order their lives,

but the need for informal and formal rules to order them is universal,

to make successful human life possible. Please forgive me for using a simple and quite crude

example using ordinary language. Suppose while you are attending

some social gathering, you develop an intestinal cramp and really want to fart to relieve the

pressure, probably you won’t, but why not? After all, you’d feel so

much comfortable if you did. You won’t because there

are rules of etiquette and social norms that reject such

intentionally boorish, rude behavior for which you might be ridiculed,

criticized, or socially excluded. You won’t fart either because you agree

with the rule, have made it your own by internalizing it, or because you fear the

consequences for violating it, or both. Customs and morality are similar

sets of rules that order our lives. All these systems of rules have

their own enforcement mechanisms, again ranging from social exclusion

to criticism and condemnation. Law is yet another human intervention

of a system of rules to regulate our interpersonal life, generally, and

to moderate conflict in particular.

What is distinctive about law

however is that the creation and enforcement of legal rules is accomplished

by the state, including its near monopoly on lawful force, even when a legal

dispute is between two private parties. If the parties can not resolve

their disagreement privately, they go to law to adjudicate the conflict

and enforce the outcome if necessary. Well, all of us are acting in the shadow

of the law which gives us reason to behave one way or another. No blind instinct necessitates

adherence to the rules and indeed we often violate them. But the rules always give us explicit and

implicit reasons for action even when we habitually and

unthinkingly follow them. With this simplified understanding

of what law is in mind, let us turn to what is

distinctive about criminal law.

Let us begin with a simple, but realistic

example that is not for the faint hearted. Imagine an aggressive 21 year-old

man who enjoys driving at very high speeds on the highway,

behaving dangerously thrills him. One day he is driving at 75

miles per hour in the middle of the day on a semi-urban undivided roadway

that has one lane in each direction, a 45 mile per hour speed limit,

and intermittent traffic lights. He sees that a traffic light

up ahead is about to turn red. Although not drunk, his blood alcohol

is just above the legal limit. Instead of slowing down and stopping as he

should, the man decides to run the light for the fun of it and speeds up to more

than 90 miles an hour to make the light. Alas! The light turns red just as he

reaches the intersection and a crossing vehicle properly enters it. Our driver crashes into the hapless

other vehicle, killing the driver and paralyzing the passenger,

who is irreversibly quadriplegic. The physical evidence and

eye witnesses leave no doubt about the driver’s exceptionally

dangerous behavior and a breathalyzer test confirms that his blood alcohol

content was above the legal limit. How does united state law respond to

such an unnecessarily sad tragedy?

First, the families of the victims

could sue the driver for civil damages to compensate them for

the harm done by his negligent behavior. This is a province of tort law. The legal rules that deal with

certain types of civil harms including personal injury. This course on introduction to

law includes a module on torts. Of course, money can never replace a human

life or fix irreversible disability. But the point of civil damages is to

try and make the victims as whole as possible given the inevitable

limitations of money as a remedy. But the driver’s behavior also

manifests massive moral indifference to the rights and interests of others. It was a gross violation

of the duty we all owe each other to avoid unnecessary harms. Compelling the driver to pay money

damages seems an insufficient response. His behavior seems to call for a public response on behalf of society for

societal blame and punishment. This is the province of the criminal law. Crimes are distinct from civil wrongs

because crimes morally wrong all members of society and are prosecuted by

the state rather than by private parties. Reflecting this distinction criminal

cases are titled, not Smith versus Jones. Rather they are the titled The People

versus Jones, or the State versus Jones, or the United States versus

Jones in federal criminal cases.

Crimes or wrongs against we the people,

as well as the individual victims.

Criminal law and tort law and both methods of regulating our lives

together and they share some goals. Each involves some degree of blame and

each includes sanctions, but only criminal law is based fundamentally

on moral values about what we owe each other, and

then imposes state blame and punishment for the gross failures of

obligation that occur all too often.

State blame and punishment are the most

severe impositions of state power, because they involve official public

blame and stigma and the infliction of punishment, that is, the infliction of

pain, because the offender deserves it. Because criminal blame and

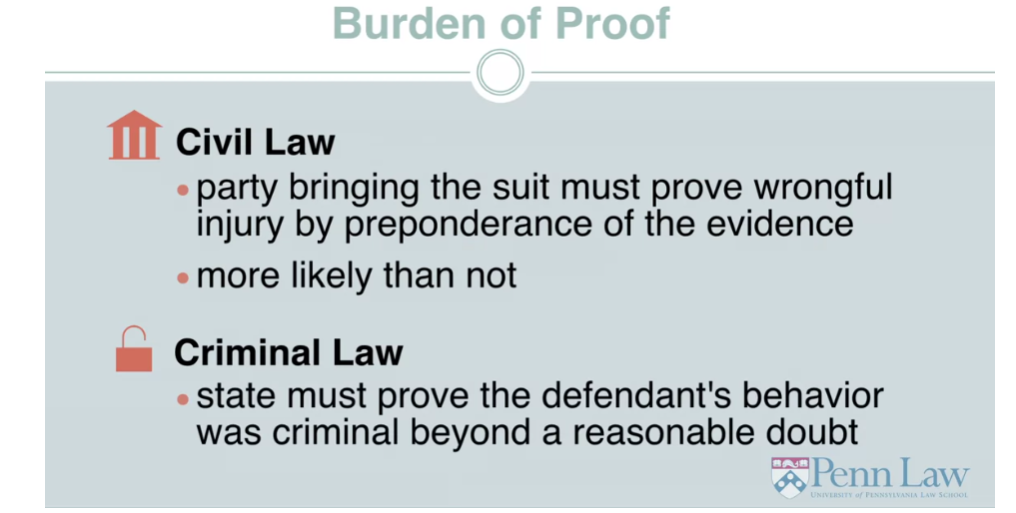

punishment are such severe inflictions, there is a different level of burden

of proof in civil and criminal law.

In civil law, the party bringing the suit must prove the wrongful injury by a standard known

as the preponderance of the evidence, which is interpreted to

mean more likely than not. In other words, if the evidence slightly

favors the plaintiff, that is, the party who is seeking compensation, the plaintiff

wins and the defendant must pay damages. In criminal law by contrast, the state

must prove that the defendant’s behavior was criminal beyond a reasonable doubt,

this does not mean beyond any doubt. That degree of certainty is beyond

human capacities in most cases. But before the state can impose blame and

punishment, it must demonstrate with a very high degree of certainty that

the defendant’s conduct was criminal. We impose such a high degree of burden on

the prosecution because the consequences are so potentially grave to the defendant. We favor the error of acquitting

the guilty to the error of convicting the innocent. The differing levels of burden of proof

thus reflect how much more is at stake in a criminal prosecution than

in a private civil lawsuit.

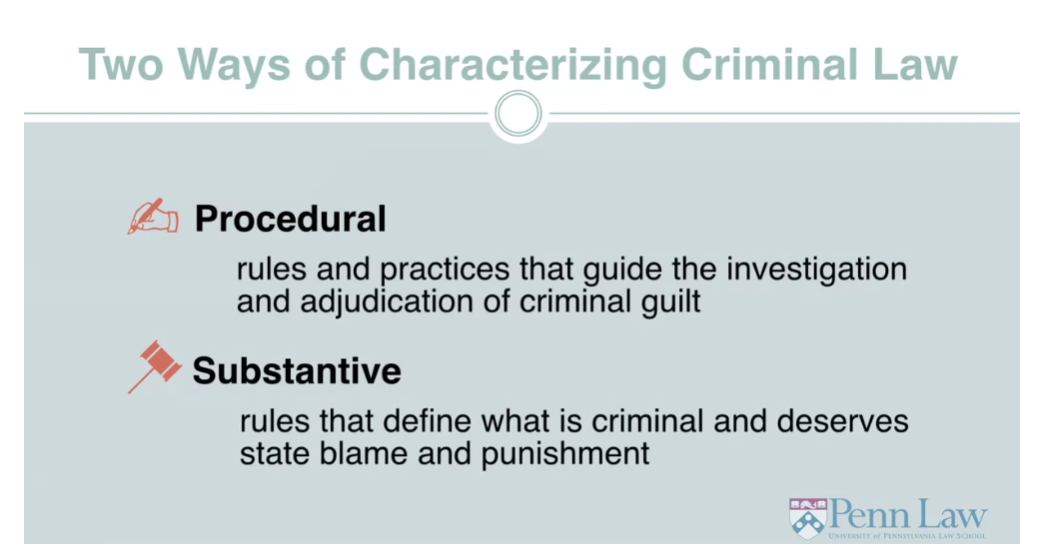

Let’s now draw an important

distinction between two ways of characterizing criminal law. The first is procedural. Those rules and

practices that guide the investigation and adjudication of criminal guilt. These rules such as the right

to remain silent and the right to be provided with

an attorney are familiar to most people. They’re extremely important and help

protect citizens from unjustified state interventions in their lives but they

are not the main subject of this lecture. Rather, in the remaining time, we’ll be talking about what is known

as the substantive criminal law. Those rules that define what

behaviour is criminal and deserves state blame and punishment.

These rules are codify by the state and federal legislatures and are then

interpreted and applied by courts. In the United States, England, Canada, and

other countries originally influenced by English law, we have what is known

as a common law legal system. Judicial interpretation is far more

important to the development of the law in common law countries than in

so-called continental legal systems, and our process is considerably

more adversarial. Despite these procedural differences

however, the definitions of crimes and defenses in common law and continental penal codes are,

on the whole, remarkably similar. Most criminal cases in the United States

are disposed of by plea agreements, so-called plea bargains, by which

the defendant agrees to plead guilty, thus saving the government the time,

trouble, and expense of trials. In exchange, the prosecution usually

agrees to a lesser charge or recommends a less severe

sentence than might have been imposed if the defendant

were convicted at trial.

Virtually all judges routinely accept

such prosecutorial recommendations. In our system, about 98% of federal criminal cases,

and about 94% of state cases, are resolved in this way, and thus trials

are a rarity compared to peer nations. In the United States,

the rules of substantive criminal law are simply the backdrop in the shadow of

which the prosecution and defense bargain. Now, let’s talk about justifying

state blame and punishment. I have said that criminal law’s special

province is the infliction of state blame, stigma, and punishment on wrong doers. Such infliction is intentional and

thus raises the immediate question of how the state can justify

such harsh treatment. After all, intentional pain infliction morally

requires justification if anything does. What goals justify such state action? The most fundamental answers are that,

the criminal law aims to do justice by giving wrongdoers what they deserve, and

it seeks to control crime in two ways. By deterring would be wrongdoers from

committing crimes, and by imprisoning criminals who would be dangerous if

they were at large in the community. Let us consider both of these goals, giving people what they deserve and

crime control in a bit more detail.

The technical term for

the justification for inflicting blame and punishment because

the defender deserves it is retribution, which is also known as just deserts. Retribution is a theory of justice that

aims to give people what the deserve. It should not be confused with imposing

revenge, which is a common psychological desire when people have been wronged but

that is not a justification of punishment.

According to a retributive

theory of justice, it is simply right in itself to

give people what they deserve. Retribution is therefore, no different

from similar theories of justice in property law, in which people are thought

to deserve fair compensation for the fruits of their labor. Or contracts,

in which people deserve compensation if others break their promises. In general, in the United States we

believe that no one should be blamed and punished criminally

unless they deserved it. It would this be unfair and unjustified

to convict people known to be innocent, even if doing so

increased crime control. We also believe that people should not

be punished more than they deserve. Thus, desert is a necessary condition

before the state can impose blame and punishment and it sets a limit beyond

which punishment would be unjust. Interestingly, there is

substantial experimental and other empirical evidence to suggest that

most people are strongly disposed to blame and punish those who deserve such

treatment, even if the imposition of punishment is costly and seems to

produce no other good consequence.

The questions raised by this justification

of retribution are, when people deserve criminal blame and punishment

rather than some other response, and how much blame and punishment is deserved

for specific types of criminal conduct. Crime control is a justification

that aims directly to produce the good consequence of

cost effectively reducing crime. Although crime can be controlled by

many means other than the threatened or actual imposition of layman punishment,

such imposition may be especially effective because

the imposition is so painful. The goal is not to prevent all crime,

such a system which is anyway probably a fantasy would be

too harsh and intrusive on liberty. The question then is, when the criminal

law is the most appropriate means to control behavior consistent with

other values we endorse, such as, the right to liberty, to pursue our

projects without undue state interference and

the right to be free of blame and punishment unless they

are genuinely deserved. Although retributive and crime control goals can be complementary,

sometimes they can conflict. For example, we might believe that

a criminal defendant’s mental abnormality makes the defendant

less blame worthy because the abnormality interferes

with his capacity to use his reason. Thus perhaps, the defendant deserves

a somewhat lesser sentence than other defendants who committed the same

crime but had no mitigating condition. On the other hand, the same abnormality

might also make the defendant particularly dangerous, and thus a candidate for

even longer than usual sentence. Balancing such goals

can be a daunting task, as we shall see when we

discuss sentencing later. This is a good time to take a break,

when we continue, we will turn to the principles that

guide the definitions of crimes. [MUSIC]

Criminal Law: Part 2

[MUSIC] With the goals of criminal law that

we discussed before the break, retribution and crime control, in mind. Let us turn to how society

defines criminal behavior. It is often said that the entire body of criminal law can be

described by two principles. The harm principle and

the fault principle.

The harm principle tries to pick

out those behaviors that produce such substantial and unjustified harms,

or such risk of harm, that the criminal law is

the appropriate response. Some harms,

such as the use of force, theft, and fraud are the so

called core of the criminal law. Familiar examples are homicide, rape,

arson, and stealing another’s property. They involve substantial harm to others,

and their prohibition is uncontroversial and found in all

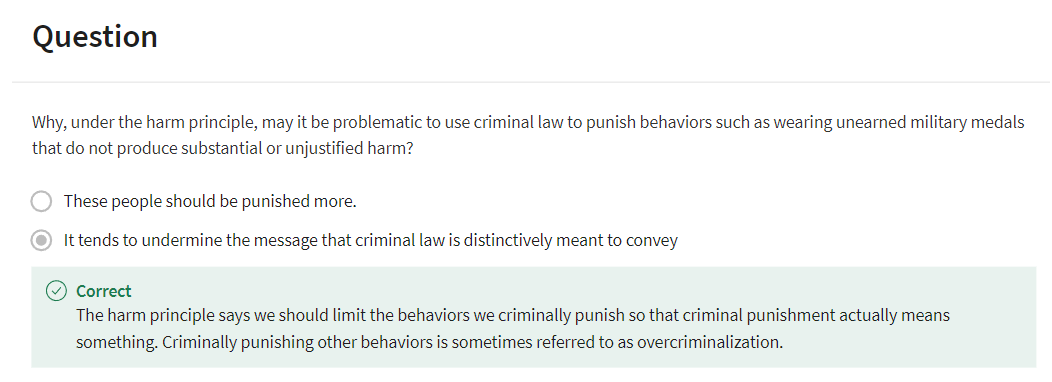

mature systems of criminal law. In the last century however, and

increasingly in recent decades. Criminal law is used to address

a wide variety of potentially problematic activities that are none

the less not obviously sufficiently clear violations of the duties we owe each other

to warrant societal blame and punishment. For example, do you think that a person

should be convicted of a crime and sentenced to prison for passing oneself off as the war hero by

wearing medals the person did not earn? It’s insensitive and immoral behavior

like intentional emotional cruelty, but should it be regulated with criminal

law and potential imprisonment? Congress thought so and

passed the stolen valor act of 2013, which the President signed into law. Should prostitution be a crime? Or should it be dealt with by

public health measures and other forms of non criminal regulation? Such expansive use of the criminal

law is controversial. Because it is not clear that

criminal law regulation is morally appropriate and necessary. And employing the criminal law

when it is not appropriate, and not necessary tends to undermine

the moral message that the criminal law distinctively is meant to convey.

A current example of the issue of

the appropriate use of the criminal law is the extensive law enforcement

approach to branding the use recreational use of abusable drugs, other

than alcohol and nicotine, of course. There’s substantial debate about

whether criminal law regulation as the primary means to prevent drug use

is a wise and cost effective policy. More generally, criminal law as a

regulatory tool, has become so expansive. That is unclear that the harm

principle is now use to limit the proper reach

of the criminal law. It is often said that our Federal

system provides 51 laboratories, the 50 states, and the Federal Penal Code

for trying to produce the best policies. This permits substantial experimentation

and responsiveness to differing values and attitudes in different jurisdictions

rather than a one size fits all approach. Moreover in our legal order,

the Constitution places almost no limits on the ability of a jurisdiction

to criminalize an activity. That is, the various states and the federal government have essentially

no restrictions on the type of conduct within their jurisdiction, that

they can prohibit using the criminal law. Exceptions are infrequent,

are never usually based on a conflict between the prohibition and

another constitutional value.

To return to the example of the stolen

valor act raised shortly ago. The Supreme Court found an earlier version

of the act that prohibited lying about military heroics unconstitutional, because it violated the First Amendment’s

protection of free speech. Otherwise, it would have been perfectly

acceptable to criticize such unsavory, but not terribly harmful behaviour. Another unusual example, is a case in which the Supreme Court held

that it was unconstitutional to blame and punish a person simply for

the status of being a drug addict. Not for use, not for

possession, but simply for the status of being a drug addict. Because statuses are not actions. They are not behavior and thus they

are beyond the reach of the criminal law. But such instances are indeed unusual.

Despite the variation that our

federal system permits there are none the less substantial similarities

among the various criminal codes, that they all start from similar legal and

cultural heritage. Now let us turn to the fault principle. This is the principle that guides

who deserves criminal blame and punishment for the behavior that we

wish to prevent using the criminal law.

Examples of such behaviors are killing

conduct, non-consensual sexual contacts, burning of buildings,

takings of another property, and the like. All these harms can be caused

without fault if a person was acting as carefully as one could

expect under the circumstances, but caused an accident nonetheless. Accidents happen without fault. Indeed, the only way to prevent all

accidents would be to completely cease all interpersonal human interaction. When innocently cause harms occur

such cases are occasions for regret, but hardly for

criminal blame and punishment. Indeed if the harm doer, and

note that I say harm doer and not wrong doer was sufficiently

careful victims of the accident would not even

be entitled to tort damages. Because the harm doer did not

violate the reasonable standard of care that is the touchstone

of tort liability. So if causing a harmful result by one’s

behavior is not a sufficient condition for blame and punishment, what is

the essence of the fault principle? We can best start to explore

this question with a quote from former Supreme Court Justice

Oliver Wendell Holmes. Justice Holmes wrote that even a dog knows

the difference between being stumbled over and being kicked.

Just so the law and ordinary morality,

I should add, assess for not just on the basis of results or

outcomes of our behavior, but more importantly on the basis of the

mental state with which the person acted. An intended harm,

a violent kick of an enemy is vastly more blameworthy than an accidental kick

that is equally painful to the victim. Mental states are the royal

road to moral fall.

The mental state with which a person

engages in potentially harmful behavior is the best indication of the

person’s attitudes towards the rights and interests of fellow people. If someone is being as careful as

humanly possible, then the person has manifested complete respect for

the rights and interests of others. If the person has intentionally caused

the harm without any justification then the person has demonstrated

that the rights and interests of the victim do not matter. Such indifference is the essence of

moral fault and blameworthiness. The mental states that make conduct

criminal violations are knows as the mens rea. This is an old Latin term that

literally means a guilty mind. But this is misleading. A more precise meaning would

be the mental state that is part of the definition that makes

a specific behavior a crime.

There is nothing problematic

about forming intentions. We do it unproblematically all the time. I am intentionally

delivering this lecture and you are intentionally listen,

listening to it. But there is nothing criminal about

delivering or viewing an academic lecture. But as we just saw,

the mental states that accompany various potentially harmful behaviors distinguish

how blameworthy the person is. Is the combination of acting in prohibited

ways coupled with a mental state indicating culpability that

are the pre-conditions for fault. The criminal law is littered with

mental state terms that are parts of the criteria for crime. Often such terms are confusing. But, in the last half century, a law

reform organization based in Philadelphia, the American Law Institute,

has published a model penal code that identifies blame worthy

mental states with some care. Although it is only a model code, and

it is not binding on any jurisdiction,. It has had enormous

influence on the reform and evolution of criminal law, since it

was published in the early 1960’s. It identifies four culpable Mental States. Purpose, Knowledge,

Recklessness, and Negligence.

这四个概念是在法律领域中用来描述不同的心态或心理状态,涉及到罪责和过失程度的判断。下面是它们的区别:

-

Purpose (Purposefully / Intentionally):

- 意图:这意味着行为者有目的地、故意地进行某种行为,他们有明确的目标,希望实现某种结果。

- 例子:一个人故意偷窃,他们明确知道他们在做什么,并且故意选择违法行为。

-

Knowledge (Knowingly):

- 知情:这表示行为者知道他们正在做的事情,他们知道自己的行为可能会导致某种结果,即使他们没有明确的意图。

- 例子:一个人购买了被盗窃的物品,他们知道这个物品可能是被盗的,但他们并没有直接参与盗窃行为。

-

Recklessness (Recklessly):

- 鲁莽:这指的是行为者明知自己的行为可能会造成危险或损害,但他们故意忽视了这种危险,继续进行行为。

- 例子:一个人在酒后驾车,明知这样做可能会导致交通事故,但他们选择继续驾车。

-

Negligence (Negligently):

- 疏忽:这表示行为者没有尽到必要的注意义务,他们在某种程度上没有采取合理的预防措施,导致了某种损害或不良结果。

- 例子:一个商家没有及时清理地面上的水渍,导致顾客滑倒受伤,这是因为商家疏忽没有采取必要的安全措施。

总的来说,这些概念代表了法律中不同程度的故意和过失,对于确定罪责和法律责任非常重要。

Let me use an oversimplified example

of homicide to define them for you. Purpose has it’s ordinary

language meaning. That is, to do something on purpose. The result is your conscious goal. So if I kill purposely, this means

that I meant to kill the victim, I did it on purpose. Knowledge means simply that

you are aware of some fact, or practically certain that it is true. Suppose for example I want to blow

up a plane to destroy the cargo so that I can collect insurance proceeds. The crew, of course,

dies in the explosion. Was it my true purpose to kill them? Not necessarily, I may even have foolishly

hoped that a miracle would occur, and that they wouldn’t die. Nevertheless, I knew it was practically

certain that the crew would die and I would be guilty of knowing homicide. To define the other culpable mental state

terms, recklessness and negligence. Let us return to the example of

our speeding driver which this lecture used earlier. The driver certainly did not have

the goal that someone should die and he was not practically certain that

someone would be killed as a result of his enormously dangerous driving. But he created an immense

amount of risk of death. That was completely unjustified

under the circumstances. Recklessness means that the person is

actually aware of a risk he is creating. It is actually in his mind, but he decides to run that risk

despite recognizing the danger. The driver would thus be guilty

of reckless homicide if he was actually aware of the risk of set,

of death or serious bodily injury, but he decided to run the light anyhow for

no reason with any social justification.

Negligence is defined as being unaware

of a risk a person has created. But under conditions in which a reasonable

law abiding citizen should have been aware of the risk. The person that’s failed to pay

the kind of attention we expect of each other when creating

unjustified risks. Even if our driver was somehow

not aware of the risk of death or serious bodily harm he was

creating by his dangerous driving. He certainly should have been aware. In criminal law, the amount of

risk that must be created for criminal liability is greater than in

tort law, reflecting the criminal law’s concern with sufficient culpability to

justify, state blame, and punishment. Remember that I said that the mental

mental state accompanying behavior is an indication of the person’s

attitudes towards the rights and interests of others who might

be effected by the behavior. The more indifferent someone is,

the more blame worthy. And they are almost certainly more

dangerous if they are more indifferent.

The four mental states I have defined,

purpose, knowledge, recklessness, negligence,

represent an imperfect, but good hierarchy of different

levels of blame worthiness. To continue the homicide example,

killing purposely or knowingly is more indifferent and

generally more dangerous than killing by the creation of risk with

awareness of the risk. Which is in turn more blameworthy than

killing without awareness of risk, but one, but when one should

have been aware of the risk. And the severity of punishments that may

be imposed reflect such different levels of blame worthiness, even when the result,

such as death, is the same.

There is one major exception to

the full principle in the United States criminal law. So called crimes of strict liability. These permit criminal blame and punishment, simply for engaging in

the preminal, in the prohibited conduct. Even if one’s behavior was blameless. For example, shipping certain goods

in interstate commerce without a proper label may be a crime. Imagine a midsize business

that is a wholesaler and distributer of pharmaceuticals. The firm packages and

labels the drugs before shipping them. Suppose one batch is not properly labeled, all though the firm management had

instituted exceptionally fine training and quality control for the labeling

process there is no perfect process. Innocent accidents happen, and the

business and it’s officers are blameless. Depending on the circumstances the

officers and perhaps the business itself are nonetheless criminally liable,

and may be blamed and punished. Such crimes largely

address public health and safety issue and carry light

punishments and stigma, but not always. Some strict liability crimes

carry heavy penalties. Such crimes, and there are many,

many in contemporary criminal codes. Are extremely controversial

because they potentially blame and punish people engaging in legitimate

activities in blameless fashion.

Given the immense importance of fault in

criminal law, the question is whether it is fair to use the criminal

law to regulate such behavior. Especially since other forms of

regulations such as civil fines might be equally effective. Having considered the harm and fault

principles that guide the definition of crime, we will turn to the actual

structure of criminal guilt after a break. [MUSIC]

Criminal Law: Part 3

[MUSIC. Welcome back. Let’s begin this section with

the discussion of the structure of criminal guilt. That is, how the state

establishes criminal liability. The structure of guilt, criminal guilt,

includes what is known as the prosecution’s prima facie case, and

what are termed affirmative defenses.

“the prosecution’s prima facie case” 意指检方所提出的“初步证明案件”,在法律上指的是检方提出的足以支持对被告提起指控的证据和事实。这种证据足以在未经证实的情况下建立对被告的责任或犯罪嫌疑,而不需要进一步的证据或推论。

换句话说,如果检方能够提出足够的证据来建立案件中所指控的事实,以至于在合理的推论下可以认定被告有罪或有犯罪嫌疑,那么就可以说检方已经建立了"prima facie case"。这并不意味着被告被正式定罪,而是表明有足够的证据将案件提交给法庭审理,让法官和陪审团进行进一步的审判和裁决。

At first I’ll be speaking

rather abstractly, but don’t worry,

I’ll soon give concrete examples. The definitional criteria for

culpability for criminal offenses are what lawyers

call the elements of the crime. They are typically defined by statute, although courts may later interpret

the meaning of these criteria. These elements are known

as the prima facie case. The constitution requires

that the prosecution must prove the definitional elements of

an offense beyond reasonable doubt. If the prosecution cannot prove any one

of the elements of the charged crime, the defendant will be

acquitted of that crime. Although the defendant may be

guilty of some other crime, for which the prosecution can

prove all the elements. If the prosecution can

prove the prima facie case, all the definitional elements of

the crime beyond a reasonable doubt, the defendant will be guilty unless,

and it is a very big unless, the defendant can establish what is

known as an affirmative defense. Affirmative defenses are also

defined by their elements.

“Affirmative defenses” 是指被告在法庭上提出的一种辩护手段,用于否认或减轻被指控的罪行。与一般的否认辩护不同,肯定辩护要求被告提供额外的证据来支持其辩护。

举例来说,如果被控犯有盗窃罪,但被告声称自己行为是为了保护自己或他人的财产,这就是一种肯定辩护。在这种情况下,被告需要提供证据来证明自己的行为是合理的、必要的,并且符合法律规定的辩护条件。

肯定辩护通常要求被告提供证据来支持他们的主张,而不仅仅是对控方提出的指控进行否认。在一些司法体系中,如果被告成功地提出了肯定辩护,法庭可能会撤销对其的指控,或者降低其所面临的刑罚。

Even if the defendants conduct

met the prima fascie case, the defendant will avoid guilt if

an affirmative defense is established. The United States Constitution permits

placing the burden of proof for affirmative defenses on the defendant

if a jurisdiction wants to do this, and many do for some affirmative defenses. In some, criminal guilt requires

proof beyond reasonable doubt of the prima facie case, and the failure

to establish an affirmative defense. Guilt is avoided, the defendant will

be acquitted and legally innocent of the crime charged, if either

the prosecution cannot prove the prima facie case beyond a reasonable doubt or

an affirmative defense is established.

Let us now use a concrete

example based on a real case, Clark versus Arizona, that reached

the United States Supreme Court. Eric Clark was riding in his

pick-up truck in Flagstaff, Arizona when he was stopped

on a routine traffic stop by officer Jeffrey Moritz who was in full

uniform and driving his police cruiser. The stop quickly turned deadly

as Clark shot and killed Moritz. Clark was charged with

the murder of a police officer. In Arizona, the crime was defined

as follows, intentionally, or knowingly killing a law

enforcement officer, who also had to be a person,

obviously, in the line of duty. Note that this particular form of homicide

focuses on the identity of the victim. It carries enhanced penalties because we

believe that killing an official member of the government,

who serves to protect all of us, is more serious than the already

serious killing of a civilian. Thus, such defendants are more culpable

if all of these elements are proven, and we want to deter such conduct

with higher penalties, especially to protect police officers. Thus, the prosecution’s case was

to prove that Clark killed Moritz, that Clark killed Moritz purposely or

knowingly. And that Clark knew that

Moritz was a human being and a police officer acting

in the line of duty. But even if the prosecution was able to

prove this prima facie case, suppose Clark killed because someone threatened to

kill him if he didn’t kill Moritz. Or suppose Clark suffered from

a sever mental illness, and delusionally believed that Moritz

was about to kill him, Clark. In either case,

maybe Clark shouldn’t be found guilty. Even if the prosecution can prove that he

intentionally killed a police officer, knowing he was a police

officer in the line of duty.

We shall use this example as we

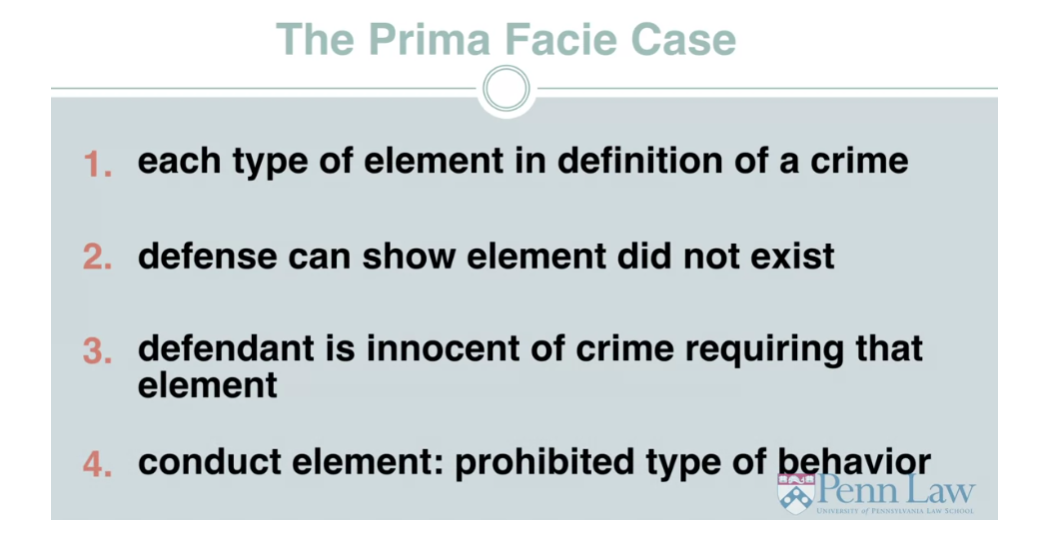

examine the prima facie case, and affirmative defenses in more detail. In this section I will discuss each

type of element in the definition of a crime and how the defense can try to

show that the element did not exist, and thus that the element is innocent of

the crime requiring that element. Each crime includes a conduct element,

a prohibited type of intentional behavior.

In the Clark case, the conduct is any

type of intentional killing conduct. So, it wouldn’t matter if Clark

intentionally shot Moritz, stabbed him, bludgeoned him, strangled him,

or pushed him off a cliff. This requirement that the defendant

intentionally engaged in prohibited conduct is known

as the act requirement. After all, if the defendant’s bodily movement was not

an action, how can we blame the defendant? Suppose for example after

the traffic stop, Clarks, Clark and Moritz were talking about the ticket. Suddenly, as a result of an unforeseeable

neurological event, Clark’s arm spasmed! And struck Moritz in the head,

killing him. We would say in such cases that

Clark didn’t act at all, and can’t be blamed for Moritz’s death. In our actual case, there is simply no

reason to believe that Clark shooting at Moritz wasn’t an intentional action. So the prosecution will have little

trouble proving the act requirement.

As we saw, mental states

are the primary fault criteria. Guilt under the homicide statute

in Clark requires that when Clark intentionally shot at Moritz, he did

so with the purpose of killing Clark or knowing that a gunshot was

practically certain to kill him. This looks like another easy win for

the cross persecution, but Clark undisputedly suffered

from paranoid schizophrenia. There was evidence they had delusional

beliefs that space aliens were persecuting them. Clark claimed that he genuinely

believed that Moritz was a space alien. If we believe him, then he did not

purposely or knowingly kill a human being. His purpose or

knowledge concerns space aliens, and killing a space alien with any

mental state is not a crime. At least not yet. Clark also had to know that a particular

so-called circumstance element existed, namely that Moritz was an officer

acting in the line of duty. But even though Moritz was in uniform and

in a police cruiser, if Clark genuinely believed he was a space

alien impersonating a police officer, then Clark really didn’t know Moritz was

an officer acting in the line of duty. Indeed, if he really had this belief, he wouldn’t be guilty of reckless

homicide, because he was not aware that he was risking the life of a person by

shooting at a supposed space alien. At most, he would have been guilty

of negligent homicide because he made an unreasonable mistake

about the nature of his victim. A reasonable person would have been aware,

as Clark arguably was not, because he was acting under

the influence of a delusion, that Moritz was a person and

police officer, and not a space alien.

There are other elements the prosecution

must prove to establish guilt for criminal homicide. And there are many ways other than

introducing mental disorder evidence, that a defendant can try to cast

reasonable doubt on the elements of the prosecution’s prima facie case, but

I’m sure you get the general picture. In the event,

this case was tried before a judge. Clark waived his right to a jury

presumably because he thought a judge, who on average is more highly educated

than a juror, would better understand and sympathize with expert psychiatric or

psychological testimony. But the judge thought that the prosecution

had proven that Clark knew that Moritz was a person and a police officer, and

that Clark had killed Moritz on purpose. Thus Clark,

Clark was prima facie guilty, and would be convicted of murder unless he was

able to establish an affirmative defense.

Let us now therefore turn to

understanding the affirmative defenses. In essence,

the elements of the prima facie case do not require proving why a defendant

acted as he or she did. It is simple prima facie wrong, for example, to kill another

human being intentionally. If you do that,

you are prima facie guilty of murder. But we all understand from our ordinary

experience that people sometimes do things that at first appear wrong, but then, when

we understand why the person did them, we may think that it was

not wrong after all. Or, even if we think that it was wrong,

we may think that the person was not blameworthy because there was

something amiss about the defendant, or the situation. There are two classes of

affirmative defenses. Justifications and

excuses that follow from these observations that sometimes these things

that appear wrong, may not be wrong. And sometimes the person who does wrong,

may not be a responsible person.

Let us consider them in order,

beginning with justifications. Justifications exist when conduct

that is ordinarily wrongful, such as the intentional killing of

a human being, is in fact right or at least permissible under

the specific circumstances. To succeed with a justification, the defendant must have had a reasonable

belief that he had an objectively good reason in these circumstances to act

in ways that are ordinarily wrong. By an objectively good reason, I mean a reason that we as

a society think is a good reason. Not simply a reason an individual

thinks is acceptable from his own idiosyncratic point of view. Justifications do not require that

the person formed a correct belief about the need to act in ways that

would otherwise be wrongful. It is sufficient if their belief

is objectively reasonable. That is all we can expect of

fallible creature such as ourselves.

Self-defense is a perfect

example of a justification. We as a society believe that

people are justified in using intentional force to prevent immediate

wrongful aggression against them. Suppose I wrongfully threatened to kill

someone with immediate deadly force. My innocent victim would be justified in

protecting his own life with deadly force. He would be justified in

intentionally killing me, because the intentional killing of

a wrongful aggressor when there really is no alternative, is preferable to an

innocent life being taken by a wrong doer. Intentional killing is thus right, or at

least permissible under the circumstances. Imagine, for example, that Moritz, the police officer,

hated Clark and stopped him for the purpose of killing Clark, and Clark

responded more quickly to kill Moritz. If that had really happened,

Clark’s killing of Moritz would be justified self defense, and

he would be fully acquitted even though the prosecution prima facie

case could be established.

Other examples of justification

that include defense of others, and defense of property. Intentional harming of others

is considered right or permissible under limited

conditions in these situations. But, once again, what all

justifications have in common is that otherwise wrongful conduct is right,

or permissible under the circumstance. Notice that there is nothing wrong

with the defendant in these cases. The defendant was a responsible person,

and was simply doing the right or permissible thing in

the circumstances of the case. Before we turn to our discussion of

the affirmative defenses of excuse and the remaining topics in this introduction,

let us take a final break. [MUSIC]

Criminal Law: Part 4

[MUSIC] Welcome back to the final

section of this lecture. Let us begin with the affirmative

defenses of excuse.

“Affirmative defenses of excuse” 指的是在法庭上被告提出的、基于某种辩护理由的肯定性辩护。这些辩护理由通常是为了证明被告在犯罪行为时存在某种合理的、可以免责的情况,从而减轻或免除其责任。

常见的肯定性辩护理由包括自卫、紧急情况、精神失常、无能力行为、自愿放弃权利等。这些辩护理由通常要求被告提供证据来证明自己的行为在法律上是可以理解或接受的。

举例来说,如果被告因为精神失常而无法理解自己的行为,并因此而犯下了罪行,那么精神失常就是一种肯定性辩护理由。被告需要提供证据来证明自己在犯罪时处于精神失常的状态,并因此而无法控制自己的行为。

总的来说,肯定性辩护理由旨在证明被告在犯罪时具有一定的合理性或免责性,从而减轻其所面临的法律责任。

In cases of excuse, defendants have

done wrong, but they are not held accountable because we think there is some

reason that they are not responsible for what they did. In cases of justification, the defendant

is a responsible person who has done the right thing or

the permissible thing. In cases of excuse, a non-responsible

person has done the wrong thing. Examples of excuses are infancy,

insanity and duress. Understanding them requires

an explanation of what the law means by a responsible person.

I believe that the criminal law

quite precisely agrees with the ordinary morality criteria for

responsibility and excuse. Recall our discussion of

the types of creatures we are, the types of creatures who can

rationally be guided by reason. Now think about your implicit standards

for believing that someone is the type of person, who would be

blameworthy if they did wrong. You expect such people to have

the capacity to be reasonably rational and to have acted without compulsion. If they have this rational capacity and were not compelled,

then you would consider them responsable. In contrast, if the person does not

have the capacity to be rational, or if they were compelled to act, you would

be inclined to excuse and forgive them. The criminal laws excuses

mirror these everyday criteria. We excuse young children who intentionally

do wrong, because their capacity for rationality is not fully developed. We excuse some people with mental

disorder, because the disorder undermines their capacity to act rationally

even if they are prima facie guilty. Suppose someone threatens to kill

you unless you kill someone else. If you yield to the threat and

kill the innocent third person, we might excuse your intentional killing,

because we would conclude that the threat produced such a hard compelling

choice that we couldn’t expect you not to kill and thus you are not

responsible for the intentional killing.

A particularly hard question about excuses

is raised when a wrongdoer’s capacity for rationality was seemingly fine and no one

was threatening him, but he claims that he couldn’t control himself or couldn’t

help himself when he committed the crime. Cases of addiction or

child molestation are examples. But exploring this topic of self control,

excuses is for an advanced and

not an introductory lecture. Indeed the whole issue of

excuses is theoretically and factually complex, but once again,

you must have the general idea.

I have not previously mentioned

free will in this lecture. Free will is not a criterion for

any criminal law doctrine. And our whole system of criminal blame and

punishment, does not depend on a presumption of so called metaphysical

free will in the strong sense. That is the ability of people to act

uncaused by anything but ourselves. When we excuse, it is actually because

defendants lack rational capacity or are compelled to act, and

not because they lack free will. There is a philosophical metaphysical

debate about free will and it’s relation to responsibility

in some ultimate sense. But it is not a debate

within criminal law.

Now let us return to Eric Clark. Permit me to change the facts a bit. Supposed Clark knew Marts was a person and a police officer, but

as a result of a severe mental disorder, he delusionally believed that when Marts

stopped him, Marts was about to kill him. He therefore shot and killed Marts in the belief he needed

to do so, to save his own life. In this case he purposely took the life

of a victim, he knew was a person and a police officer, but

he acted for a crazy reason. His delusional belief,

that was a product of his disorder, rather than being caused by

his carelessness or the like. His capacity for rationality, under the

circumstances, was severely compromised, and he is a candidate for

the excuse of legal insanity.

The criteria for this excuse, and

recall that all justifications and excuses have their own criteria, are that

he was suffering from a mental disorder and, more importantly,

as a result did not know right from wrong. In this hypothetical case if we

believe him, he did suffer from a mental disorder and as a result he

didn’t know that killing Moritz was wrong. He delusionally and genuinely believed

that his own life was wrongfully in danger, and that he had a legal right

to kill Marts to save his own life. Nevertheless, it was wrong to kill Marks because

the officer was not threatening Clark. But Clark was not a responsible person

because he did not know that he was doing wrong and it was not his

fault that he made this mistake, thus he will be acquitted by reason

of the excuse of legal insanity.

Assume that its prosecution

is able to prove its case beyond a reasonable doubt and that

no affirmative defense is established. The defendant will then be found

guilty of the crime charged and deserves to be punished. At this stage we are ready for the last

part of our discussion, sentencing. The imposition of the proper punishment.

Most experienced criminal defense

attorneys will tell you that their clients care far more about whether

they will go to prison, and for how long than about whether

they are convicted. Yes, a conviction imposes blame and

stigma, but for most people, going to prison, the primary punishment in the

United States is profoundly painful and to be avoided for the many reasons

that are not difficult to imagine. Thus, the possible punishments, and

the process by which they are imposed, are of the utmost importance to

the state and to the individual. The goals of sentencing

are generally the same goals that generally justify criminal blame and

punishment. Giving offenders their just dessert and

preventing crime. But sentencing schemes are seldom

precisely clear on how these goals should be weighed and balanced in general, or how they

should be applied in individual cases. Recent decades have seen greater

emphasis on retribution and less indeterminate sentences. But the pendulum may be swinging

towards more evidence based crime control that focuses on the offenders

risk of future criminal behavior. The punishments that may be imposed for

crimes are set by the legislature, or by an administrative agency

the legislature authorizes to do this. The Supreme Court has

repeatedly held that the 8th amendments prohibition of cruel and

unusual punishments, sets almost no constraints on the terms

of years legislatures may authorize. The Supreme Court has held some

exceedingly severe sentencing schemes, such as California’s original

three strikes and you’re out law. Which permitted a sentence

of 25 years to life, for a defendant convicted of a third felony,

even if the third felony was relatively minor, and the prior

two felonies were not so serious.

There is enormous disparity across and within jurisdictions concerning

the proper sentences for various crimes. Once again,

the federal laboratory is at work. Juries decide whether the defendant

is legally innocent or guilty, and with the primary exception of capital

sentencing, judges impose sentences. Generally, the legislature provides for

a range of sentences for each crime, but is often unclear what sentences,

retribution or crime control demand. Judges therefore, have wide

discretion to decide what sentence to impose within the statutorily

authorized range. They’re typically aided in this by

non-binding pre-sentence reports prepared by probation officers, or other court personnel that address

the defendant’s background, the circumstances of the crime, and

other sentencing considerations. In some jurisdictions, judicial discretion

is constrained by legislatively mandated guidelines, or by required mandatory

minimum sentences that must be imposed.

Despite attempts to rain

in unjustified discretion, inequality in sentencing for

similar crimes committed by similar defendants remains

a disturbing phenomenon. There has been a great deal ferment

concerning sentencing in recent decades, reflecting the recognition of how

important it is to individual lives and to the society as a whole. Everyone hopes that the attention paid and the thought given will produce a more

just and effective sentencing system. But whether that result will be

achieved is an open question.

Let me conclude this section on

sentencing by pointing out another way in which the United States is distinctive. Imprisonment and fines are a common

feature across a wide range of nations, but what sets apart sentences in the

United States, compared to other developed nations, is the much greater length of

prison terms we impose for most crimes. I leave aside here, capital punishment, which among western developed nations,

only the United States imposes. Despite the controversy concerning

the moral appropriateness and crime-control effectiveness of the death

penalty, and the distinctiveness of our imposing it, it applies to so

few cases that for this lecture I will simply treat it as an example of

comparative harshness of our punishments.

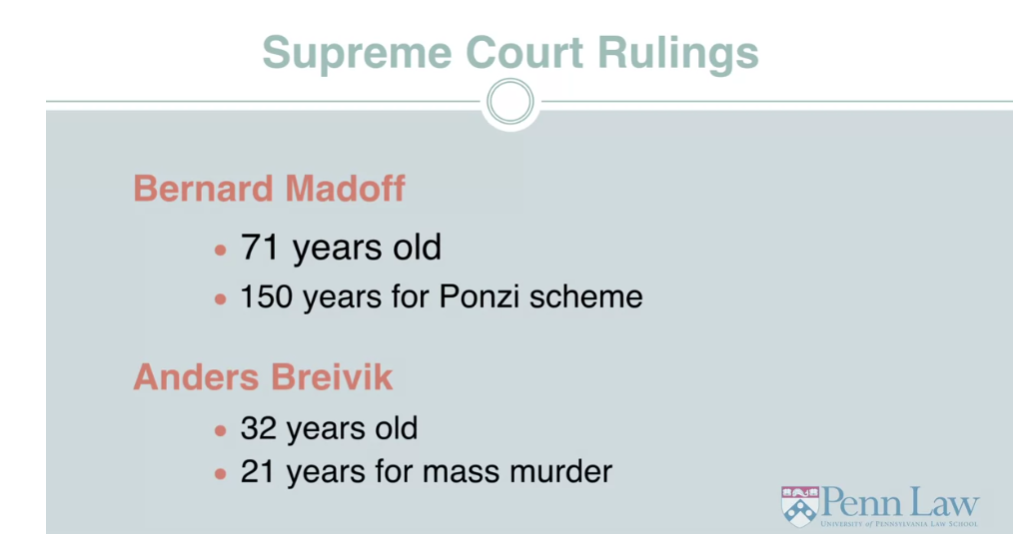

Let me therefore return to the example

of imprisonment to illustrate my point about the length of sentences. Please compare Bernard Madoff, whose massive fraud harmed in impoverished

large numbers of innocent people, wiping out retirement savings and other

crucial forms of investment, and security. To Anders Breivik,

the young Norwegian ultranationalist, who killed eight people in Oslo

bombings to create a diversion, invaded a summer youth camp for members

of a political party he despised and systematically slaughtered

69 people at the camp. Madoff, who was 71 years at the old at

the time of sentencing for his fraud, received 150 years in prison for

his Ponzi scheme. Breivik, who is 32, received 21 years for

his mass murders of 77 people.

Breivik would have to serve

at least ten of the 21 years, although, he could be detained for much

longer in Norway on non-penal grounds. Non-penal grounds,

if he were found to still be dangerous. With no lack of compassion or

respect for Madoff’s victims. I can safely say that what Madoff did was

far less blameworthy and harmful, but our law permitted a vastly greater

sentence than Norwegian law provided for Breviks multiple murders. Of course, Madoff was much older and

likely to effectively serve less time, but that is beside the point. If he had been Brevick’s age the sentence

disparity would be even clearer. It goes beyond the scope of this lecture

to explain why our sentences are so comparatively severe. And I’m here taking no position on whether

such severity is justified, but it is simply a fact that sentences in the United

States tend to be comparatively severe.

Let me say a few words in conclusion

about the future of criminal law. We have covered a lot of territory. Here is a brief speculation

about the future. As we all know from

reading the newspapers and other media, there have been major

advances from the various sciences in our understanding of

the causes of human behavior. Hardly a day goes by without

a revelation from psychology, genetics, neuroscience, and other disciplines

that study human behavior. Our criminal law is based as we have

seen on our ordinary understanding of ourselves as persons. As we learn more and more about ourselves,

will we come to see ourselves as the non-responsible victims of causal

forces over which we have no control. If so, this would justify abandoning

our practices of blame and punishment that take people

seriously as moral agents. Many think that this development

is possible and even desirable. In contrast, I think that this is

highly unlikely for many reasons. And I believe that our view of

ourselves as creatures who act for and can be guided by reason,

which is the basis of criminal law and ordinary morality as, is here to stay. And it’s a good thing too. Our current concept of personhood is

at the core of concepts like liberty. Dignity and respect and concern for people that contributes

to the richness of our lives. I believe it would be a human disaster

to abandon these concepts, and there is no scientific or

moral justification for doing so. Criminal law is a complex and

fascinating topic. I hope that you found this lecture

interesting, and that it had provided you with tools to think about criminal

justice issues as concerned citizens. Thank you very much. [MUSIC]

Criminal Law Quiz

法律英语

criminal law: 刑法

forensic:美 [fəˈrenzɪk] 刑侦的,法医的

forensic psychologist:法医心理学家

touchstone:试金石;检验标准

hapless:美 [ˈhæpləs] 不幸的,运气不好的

paralyze:使瘫痪,使麻痹

quadriplegic:美 [ˌkwɑdrɪˈplidʒɪk] 四肢瘫痪的

Our driver crashes into the hapless other vehicle, killing the driver and paralyzing the passenger, who is irreversibly quadriplegic:我们的司机撞上了另一辆倒霉的车,司机死亡,乘客瘫痪,不可逆转地四肢瘫痪

province:范围,领域;省

This is the province of the criminal law.这是刑法的范围。

prosecute:美 [ˈprɑːsɪkjuːt] 起诉

criminal law is based fundamentally on moral values about what we owe each other, and then imposes state blame and punishment for the gross failures of obligation that occur all too often. 刑法基本上是基于道德价值观,即我们对彼此的亏欠,然后对经常发生的严重失职施加国家指责和惩罚。

imposition:强加,施加

stigma:耻辱,污名

infliction:美 [ɪnˈflɪkʃən] 强加,施加

State blame and punishment are the most severe impositions of state power, because they involve official public blame and stigma and the infliction of punishment 国家指责和惩罚是国家权力最严厉的强制手段,因为它们涉及官方的公开指责和指责以及施加惩罚

burden of proof:举证责任

preponderance: 优势;多数

preponderance of the evidence

“Preponderance of the evidence” 是指在法律上一种证据标准,用于评判民事案件中的证据。这一标准要求法庭在评估证据时,只需确定某一方提出的证据是否比另一方提出的证据更有说服力,即是否更可能属实。简而言之,如果证据倾向于支持某一方的主张,即使只是稍微多一点,法庭也应该裁定支持该方的主张。这种标准通常被认为是低于“超越合理怀疑”(beyond a reasonable doubt)的标准,后者通常用于刑事案件中。

acquit: 美 [əˈkwɪt] 宣告无罪

convict: 宣判有罪

We favor the error of acquitting the guilty to the error of convicting the innocent. 我们宁可判有罪的人无罪,也不愿判无罪的人有罪。

adjudication:美 [əˌdʒudɪ’keɪʃn] 判决,裁定

plea:美 [pliː] 恳求,供词,陈述(法律上的)

plea bargain:辩诉交易;认罪辩诉协议

plead guilty: 认罪

trial:审讯

Most criminal cases in the United States are disposed of by plea agreements, so-called plea bargains, by which the defendant agrees to plead guilty, thus saving the government the time, trouble, and expense of trials. 美国的大多数刑事案件都是通过认罪协议处理的,即所谓的辩诉交易,被告同意认罪,从而为政府节省了审判的时间、麻烦和费用。

retribution:应得的惩罚,报应

deserts:应得的惩罚

The technical term for the justification for inflicting blame and punishment because the defender deserves it is retribution, which is also known as just deserts. 因辩护人罪有应得而对其施加责备和惩罚的理由的专业术语是报应,也称为正义的报应。

homicide:美 [ˈhɑːmɪsaɪd] 谋杀,凶杀

arson:美 [ˈɑrs(ə)n] 纵火

Familiar examples are homicide, rape, arson, and stealing another’s property. 常见的例子有杀人、强奸、纵火和盗窃他人财产。

prostitution:美 [ˌprɑːstɪˈtuːʃn] 卖淫

Should prostitution be a crime? 卖淫应该是犯罪吗?

blameworthy: 应受谴责的

blow up:使爆炸

Suppose for example I want to blow up a plane to destroy the cargo so that I can collect insurance proceeds. 假设我想炸毁一架飞机来摧毁货物,这样我就可以获得保险金。

culpability : 美 [kʌlpəˈbɪlətɪ] 有过失,有罪

paranoid:美 [ˈpærənɔɪd] 有偏执狂特征的,妄想的

schizophrenia:美 [ˌskɪtsəˈfriːniə] 精神分裂症,人格分裂

Clark undisputedly suffered from paranoid schizophrenia:克拉克毫无疑问患有偏执型精神分裂症

infancy:幼年;婴儿期;

insanity:美 [ɪnˈsænəti] 精神错乱,精神病

duress:美 [d(j)ʊˈrɛs] 强迫,胁迫

Examples of excuses are infancy, insanity and duress:借口的例子有婴儿期、精神错乱和胁迫

child molestation :儿童性骚扰

“Child molestation” 是指对儿童进行性侵犯或性虐待的行为。这包括对未成年人进行性侵犯、性骚扰、性行为或其他不当性行为的行为。这种行为是严重的犯罪,对受害者造成长期的心理和情感伤害,因此受到法律的严厉惩罚。

felony:重罪

后记

2024年4月28日20点56分完成Week 5关于刑法的学习。今天是周日,但是五一假期调休,变成今天是工作日,上周四的课。