An Introduction to American Law

Course Certificate

Course Introduction

本文是 https://www.coursera.org/programs/career-training-for-nevadans-k7yhc/learn/american-law 这门课的学习笔记。

文章目录

- An Introduction to American Law

- Instructors

- Week 06: Civil Procedure

- Key Civil Procedure Terms

- Supplemental Reading

- Civil Procedure: Part 1

- Civil Procedure: Part 2

- Civil Procedure: Part 3

- Civil Procedure: Part 4

- Civil Procedure Quiz

- Week 07: Final Exam

- 法律英语

- 后记

Instructors

Anita Allen, Henry R. Silverman Professor of Law and Professor of Philosophy, Penn Law, University of Pennsylvania

Shyam Balganesh, Professor of Law, Penn Law, University of Pennsylvania

Stephen Morse, Ferdinand Wakeman Hubbell Professor of Law; Professor of Psychology and Law in Psychiatry; Associate Director, Center for Neuroscience & Society, Penn Law, University of Pennsylvania

Theodore Ruger, Dean and Bernard G. Segal Professor of Law, Penn Law, University of Pennsylvania

Tess Wilkinson-Ryan, Assistant Professor of Law and Psychology, Penn Law, University of Pennsylvania

Tobias Barrington Wolff, Professor of Law, Penn Law, University of Pennsylvania

Week 06: Civil Procedure

In this module, Professor Wolff will introduce us to some of the major issues in civil procedure law. Civil procedure is the study of the rules of court that must be followed by the judge and parties in civil cases (as opposed to criminal cases – criminal procedure is a whole other area of the law, but law students learn civil procedure first because it gives the structure of typical trials). The essence of a law school civil procedure course is the study of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure. A copy of these is linked in the syllabus for you to scan. The rules tell you how to file a lawsuit and how the court must function while it is considering a lawsuit. Professor Wolff will introduce you to the doctrinal area of procedure and will highlight some of the major modern issues in procedure law.

在本单元中,Wolff 教授将向我们介绍民事诉讼法中的一些主要问题。民事诉讼程序是对民事案件中法官和当事人必须遵守的法庭规则的研究(与刑事案件相对–刑事诉讼程序是另一个完全不同的法律领域,但法学院学生首先学习民事诉讼程序,因为它提供了典型审判的结构)。法学院民事诉讼程序课程的精髓在于学习《联邦民事诉讼程序规则》。教学大纲中链接了《联邦民事诉讼规则》的副本供您扫描。这些规则告诉您如何提起诉讼,以及法院在审理诉讼时必须如何运作。沃尔夫教授将向您介绍程序的理论领域,并重点介绍程序法中的一些主要现代问题。

Key Civil Procedure Terms

Civil Procedure

Civil procedure consists of the rules by which courts conduct civil trials. “Civil trials” concern the judicial resolution of claims by one individual or group against another and are to be distinguished from “criminal trials,” in which the state prosecutes an individual for violation of criminal law. “Procedure” is to be distinguished from “substantive law” in that substantive law defines the rights and duties of everyday conduct, such as in contract law or tort law. For more, click here: http://www.law.cornell.edu/wex/civil_procedure.

Federal Rules of Civil Procedure (FRCP)

These govern civil procedure in United States federal courts. The FRCP are promulgated by the United States Supreme Court pursuant to the Rules Enabling Act. For more, click here: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Federal_Rules_of_Civil_Procedure.

Key Terms:

antitrust laws

Federal and state laws created to regulate trade and commerce by preventing unlawful restraints, price-fixing, and monopolies. The laws are intended to promote healthy market competition and encourage the production of quality goods and services at the lowest prices. The primary federal antitrust laws are the Sherman Act and the Clayton Act. (http://www.nolo.com/) This was the subject matter of the famous Twombly decision discussed in the lecture.

arbitration

An alternative dispute resolution method with one or more persons (private persons, not judges) hearing a dispute and rendering a binding decision (as an alternative to going to court). An agreement to arbitrate disputes can be made before or after a specific dispute arises. Since the parties can agree to the rules of arbitration (e.g., selecting qualified arbitrators with knowledge of the issues), they can save costs as compared to litigation. (http://www.law.cornell.edu/wex/arbitration).

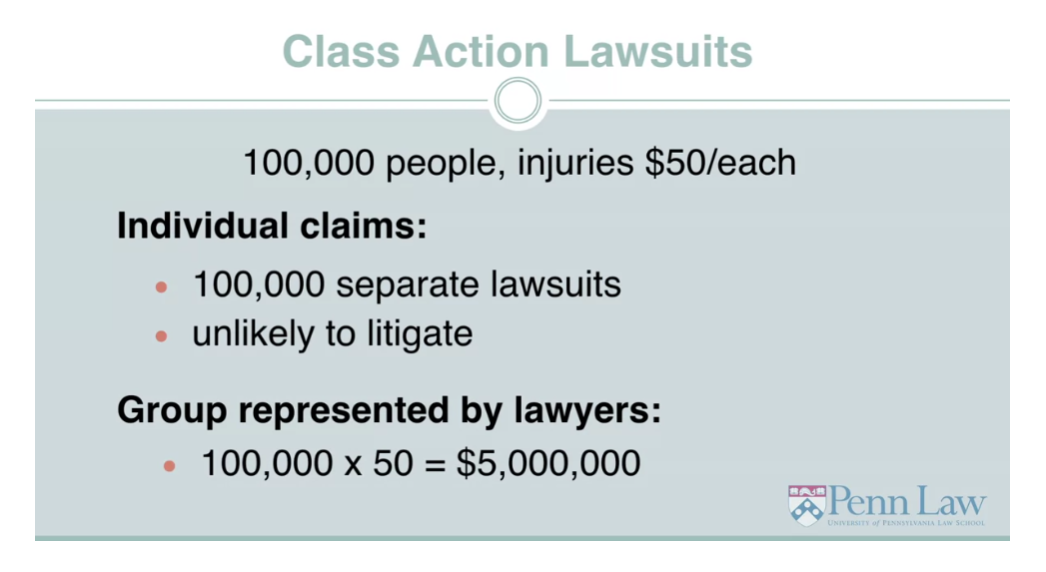

class action

A class action is a procedural device that permits one or more plaintiffs to file and prosecute a lawsuit on behalf of a larger group, or “class.” Put simply, the device allows courts to manage lawsuits that would otherwise be unmanageable if each class member (individuals who have suffered the same wrong at the hands of the defendant) were required to be joined in the lawsuit as a named plaintiff. For more, click here: http://www.law.cornell.edu/wex/class_action.

complaint

The pleading that starts a case. Essentially, a document that sets forth a jurisdictional basis for the court’s power, the plaintiff’s cause of action, and a demand for judicial relief. For more, click here: http://www.law.cornell.edu/wex/complaint.

contract of adhesion

A standard form contract drafted by one party (usually a business with stronger bargaining power) and signed by the weaker party (usually a consumer in need of goods or services), who must adhere to the contract and therefore does not have the power to negotiate or modify the terms of the contract. For more, click here: http://www.law.cornell.edu/wex/adhesion_contract_contract_of_adhesion.

Federal Arbitration Act

A statute that protects the integrity of many arbitration agreements by making them binding and limiting the reasons for which courts can review and set aside arbitration awards. (http://www.law.cornell.edu/wex/federal_arbitration_act)

Rules Enabling Act

An act passed by Congress in 1934 that gave the Supreme Court the power to make rules of procedure and evidence for federal courts as long as they did not “abridge, enlarge, or modify any substantive right.” (http://www.law.cornell.edu/wex/rules_enabling_act_of_1934)

pleading

Pleading is the beginning stage of a lawsuit in which parties formally submit their claims and defenses. The plaintiff submits a complaint stating the cause of action - the issue or issues in controversy. The defendant submits an answer stating his or her defenses and denials. For more, click here: http://www.law.cornell.edu/wex/pleading

Supplemental Reading

- “Lawsuit Chronology”

- “Civil Cases: The Basics”

- “How Class Action Lawsuits Work”

- The Federal Rules of Civil Procedure (skim only)

- Excerpt from Westlaw’s Black Letter Law Outline: Civil Procedure

Civil Procedure: Part 1

[MUSIC] My name is Tobias Wolff. I’m a member of the faculty at

the University of Pennsylvania Law School. I’m standing here in Silverman Hall, which is one of the grand old

buildings of Penn Law School. It is a classroom and

was originally a part of the reading room that was a component of

the library in the original building. And my specialty here on the Law School

faculty is the related issues of civil procedure and complex litigation. And, I’m going to be talking a bit

about the field of civil procedure, what civil procedure is, and

some of the major themes and issues and problems that the fields

of civil procedure and complex litigation are dealing

with in the United States today. So for starters,

let’s get some definitions on the table. What is civil procedure? Broadly speaking civil procedure has

two components, civil and procedure. Civil in this title describes

the workings of our judicial system that have to do with the resolution

of disputes between people, or sometimes between people and government,

that are not criminal in nature. Civil disputes have to do with

disputes over ownership of property, injuries that you think you’re

entitled to be compensated for, contracts that you want to get enforced,

so forth. That is a civil dispute. Procedure describes

the mechanisms by which we use our court system to resolve disputes.

And so the field of civil procedure,

broadly speaking, is a field that relates to the use of our court systems

to resolve civil disputes between people, To resolve disputes over property,

over contracts, over injuries. And the mechanisms by which we

resolve those disputes and the ways in which our court system operates in

the resolution of those disputes. Now, the field of civil

procedure encompasses a very wide array of issues that have

to do with the power of courts, that have to do with the ways in which

people approach the resolution of their disputes, and

the power that is bound up with procedure. That is to say the power that is

bound up with these mechanism, mechanisms that we use for

the resolution of disputes. I’d like to frame my discussion about

civil procedure with a quotation from a man by the name of Karl Llewellyn. Llewelyn was a legal scholar, writing

in the first part of the 20th century. And in 1929, he wrote a series

of essays that were designed for incoming law students and that were in,

intended to introduce law students to the fields of study that

they were about to be undertaking. And it was a set of essays that were, a set of lectures that were published in

a book that was called the Bramble Bush. And when he was talking about the field

of procedure, he said the following. You must learn to read

your substantive courses, as it were through

the spectacles of the procedure. Because what substantive law

says should be means nothing, except in terms of what procedure

says you can make real.

Now, Karl Llewellyn was writing at

a time when the issue of procedure and procedural reform was really quite urgent. The procedures in our civil court

systems in the United States have not always functioned particularly well. And the early part of

the 20th century was a time when procedures were extraordinarily

varied around the country and even varied within our federal court system,

which is our national court system. And there were a lot of very active and elevated conversations [COUGH] around the

country about procedural form, reform and what procedural reform might look like. And Llewellyn was specifically writing

at a time when procedure was in danger of actively frustrating the ability of

litigants to prevail on their claims or to, to bring their claims forward in

an effective and meaningful fashion. And in particular he lived and

taught in New York at the time, and New York had a really messed up set

of procedures in their state courts. And for a series of historical

reasons at this point in time, the federal courts looked to

what state courts would do in deciding what procedures they

would use in many of their cases.

So we have, in the United States, two parallel court

systems, a federal court system and court systems in each of the 50 states,

and these are formally separate systems. And they’re allowed to use

different procedures and have many different policies surrounding

the resolution of civil disputes. And for a series of historical reasons in

the early part of the 20th century and before, the federal courts in many

respects didn’t have their own procedures, they looked to what the states did. And at the time that Llewellyn wrote that

quote, state procedures were a mess. And as a consequence a lot of federal

procedures were a mess as well. And so conversations about

procedural reform in the first 30, 35 years of the 20th century

were both conversations about what a sensible procedure

system might look like. But they were also

conversations about whether it would make sense to have a single uniform

set of procedures in the federal courts. And largely as a consequence of

the negative history, the negative experiences that lawyers and judges had

with the existing procedural system, in 1934 Congress passed this very important

statute, the Rules Enabling Act of 1934. And the Rules Enabling Act was the very

first time that Congress had provided for a single,

uniform set of civil procedures to resolve civil disputes

in our federal courts. And several years following the enactment

of this statute, rule makers carried into effect, they brought into being,

the very first set of general purpose, uniform procedural rules for

the federal court. What are often described as

the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure.

So, understanding how civil procedure

works in the United States is importantly in part, about

understanding how both the origins of our federal procedural system and

how procedures work in the federal courts. because federal courts are very important,

place where civil disputes get litigated. And also the way that our federal

courts resolve civil disputes winds up providing a model, winds up providing

a lot of guidance how many, many states adjudicate

civil disputes as well. So, in understanding civil procedure

in the United States it’s important to understand the federal

system of civil procedure. And in particular, it’s important to

understand three basic principles, which are going to be the focus of

much of my discussion here today about the American procedural system. The first basic principle involves

a term called transsubstantivity. It’s what you might think of as

a philosophical principle that underlies the federal rules of civil procedure,

and that has really served to shape, to a significant extent,

the way that we think about how a procedural system ought to operate

within the American justice system. The second basic principle is

the relationship between quote, unquote, procedure and

quote, unquote, substance. For a lot of people, particularly before

you get to law school, if you hear a term like civil procedure, you think, oh that’s

going to be the really dry, boring stuff. And that’s not remotely true at all. And this boundary between

what we label procedure and what we label substance,

it’s a really important issue. And figuring out what it means to

distinguish between procedure and substance actually winds up

being one of the key issues in the administration of

a civil justice system. And I’ll say a few words about that. The third issue that I’m going to

discuss has to do with efforts that are increasingly important in

the 21st century for litigants, and in particular for powerful defendants

like corporate defendants, to try to bargain their way out

of the civil procedure system. And to use a mechanism called

arbitration under the auspices of a very powerful federal statute called

the Federal Arbitration Act to find ways to bargain their way around

our civil justice system. So the three basic principles

that we’ll talk about in, in figuring out how exactly our civil

justice system works are, number one, this philosophical issue

of transsubstantivity. Number two this sort of practical

concern about the distinction between procedure and substance, and

what that distinction is meant to capture. And third, a recent development. A recent development of great practical

significance, of efforts of people and particularly defendants to bargain their

way around our civil justice system, and what some of the implications are for

some of those efforts. [MUSIC]

Civil Procedure: Part 2

[MUSIC] So, let’s start our conversation about

this first issue of transsubstantivity. As I mentioned, when the federal

rules of civil procedure were brought into existence, procedure had been a mess. Procedure had been a mess

in the federal courts and it was a mess in the state courts as well. And one of the goals of the enactment of

this statute, the Rules Enabling Act, and the, the bringing into being of these

federal rules of civil procedure, one of the goals was

to clean up that mess. And to create a set of mechanisms by

which people could bring their civil cases into court, that would be relatively

uniform and relatively predictable. And the principle of

transsubstantivity was one of the tools by which that goal was

sought to be carried into effect. And this is a principle that has

two concepts bound up in it. You might think of them as

vertical transsubstantivity and horizontal transsubstantivity. These are big fancy terms, but they’re really meant to capture

some very simple ideas.

First of all, this, this idea of vertical

transsubstantivity is basically an idea that says that procedures will

operate in the same basic way. That is to say, the same procedures

will apply whether a lawsuit is a big complicated lawsuit or

a small, relatively simple lawsuit. And we have one set of procedures. A very fully realized and,

and all the bells and whistles system of procedure, that apply

regardless of whether you bring a big, expensive, complicated case into federal

court or a relatively simple and relatively low-stakes

case into federal court. Now why might this matter? Well, it matters because the,

all the bells and whistles version of the federal rules of civil procedure

can sometimes be moderately expensive. And one of the facts about

the federal procedural system, which has gotten some attention recently,

is that the, the completeness of it. The fact that it makes so

many tools available for discovery, for learning information

from the other side and getting them to turn

information over to you. For motion practice, for filing formal motions with the court

in which you ask the court for various different kinds of relief at

various stages of the litigation process. It has a fully realized system of

procedure, which when it is utilized in, in, to its fullest extent, can be a relatively expensive

way of resolving disputes. And so the transsubstantivity principle

in this vertical orientation has held for the last 80 years or so,

that our federal procedure system ought to work the same way for big cases as

it does for small stakes cases.

Now, there’s a lot of benefits

that comes from that idea of vertical transsubstantivity. But also potentially some costs as well. There’s at least the possibility that

smaller cases might get priced out of the federal courts in various ways. And so one conversation about

transsubstantivity has to do with the affordability of litigation. That is to say, whether people

will have access to justice and whether one unintended consequence of

creating this fully realized system of procedure that is uniform in all of its

applications, is the possibility that certain types of cases might wind up

getting priced out of the federal courts. This is a useful issue to start with

because it focuses us on the relationship between a procedural system and

the viability of enforcing a claim, right? The cost associated with for,

enforcing a claim. That’s an issue that we’re going to

talk about a fair amount in relation to the second and third issues that we

put on the table just a moment ago. So, that’s this concept of

vertical transsubstantivity.

There’s also an idea of what I’ll

call horizontal transsubstantivity. And here,

this is a description of the way that procedure operates in

different types of cases. That is to say, different cases that are governed by

different substantive legal principles.

And one of the core concepts one of the

core philosophical principles according to which our procedure

system has operated for in, its entire lifetime,

is that procedures should not vary depending upon the type of claim

that you’re seeking to prosecute. Procedures should not vary depending upon

the substance of the claim that you’ve brought forward. So, if you’re bringing an anti-trust

claim, if you’re bringing a securities law claim, if you’re bringing a civil

rights claim, if you’re bringing a personal injury claim, very,

very different substantive law claims. Claiming very different kinds of injuries. They all use the federal rules of

civil procedure if they’re brought in the federal courts, and

it’s the same set of federal rules for all of these different types of claims.

And at least in theory, the federal rules will operate in the same

fashion according, without regard to what type of substantive claim it is

that a litigant has brought forward.

Now, that may sound like

a fairly sensible and straightforward proposition,

and indeed, in a lot of ways, this idea of horizontal transsubstantivity

has in fact been a very important unifying feature of the civil

procedure system in the federal courts. But there are times when it can also cause

problems or at least cause some confusion. And there’s a recent case that I want to

talk about, that helps to illustrate some of the problems and confusion that this

idea of transsubstantivity can introduce. It’s a case called

Bell Atlantic versus Twombly.

Bell Atlantic versus Twombly

was an anti-trust case. And it was a case specifically that

deals with pleadings standards. Now pleadings standards,

pleadings is a description of the very, very first stage of a lawsuit

where you initiate the lawsuit by filing a complaint with the court. And when you’re a plaintiff, when you’re

somebody who thinks you’ve been injured and you want to start a lawsuit, you

draft this document called a complaint. And because you’re right

at the outset of a lawsuit, you don’t have any evidence, necessarily. You don’t necessarily have any testimony

or any documents from the other side. All you can put in a complaint

is allegations, right? I allege that the following

things happened. A complaint is basically a promise for what it is that you think

you’ll be able to prove. What it is that you’re offering to

prove if you’re given an opportunity to have a lawsuit and develop evidence. It contains allegations that are supposed

to show why you would be entitled to relief from the court, if you’re able to prove the things

that you say happened to you.

So, the question of what you

have to put into a complaint in order to get into court, right? What is the threshold requirement for

initiating the very powerful processes of a lawsuit

is a matter of great concern and we refer to that question as the standard

of pleading that you have to satisfy. So, Bell Atlantic vs Twombly was a case

that involved pleading standards. It involved a dispute over

whether a complaint that had been filed by an anti-trust

plaintiff was an adequate complaint. Whether it met the standard for getting this anti-trust

plaintiff into federal court.

So, in the Bell Atlantic versus Twombly

case, the Supreme Court wound up deciding that the complaint that the plaintiff

had filed in that case was inadequate, that it failed to satisfy

the pleading standard required to allow the plaintiff to initiate the

litigation process to have a day in court.

And specifically, what the court wound up

deciding was that a very specific issue of anti-trust law. That is, how, what it is that you have to demonstrate

to establish a conspiracy in anti-trust. What it is that you have to show,

in order to establish that there has been a conspiracy to violate

the anti-trust statute. That aspect of the complaint

was insufficient and the plaintiff had not alleged enough

facts to make it, in the court’s words, plausible that there was a conspiracy

to violate the anti-trust laws.

The Supreme Court held the pleading in the Twombly case was inadequate because the plaintiff didn’t allege enough facts to make it plausible that there was a conspiracy to violate antitrust statute. This case announced that the standard of pleading is plausibility.

Now, this was an issue in

the field of anti-trust, that had a particular

a particular substantive context. Anti-trust policy is very concerned

about fostering competition, and nonetheless,

policing abuses of market power. And so the doctrines around conspiracy

in the anti-trust laws seek to draw or to strike a very careful balance between

the desire to foster competition, but to prevent certain kinds

of abuses of market power. And what the court had to say in

the Bell Atlantic versus Twombly case, about why the complaint in that

case was inadequate, were geared, to a very significant extent, to these

particular substantive policy judgements that our anti-trust laws make

about balancing the fostering of vigorous competition with

preventing abuses of market power.

So, that was Bell Atlantic versus Twombly. And after Bell Atlantic was decided,

there was a question. And the question was, is this a case

that establishes a pleading standard, a heightened pleading standard,

across the board for all kinds of lawsuits,

no matter what the substantive context? Or, is it a case that was really

about pleading and anti-trust cases? Is, is it really a case

that was specific to this concern about the substantive policy

underlying the anti-trust statute and how conspiracy operates

the anti-trust statute?

In a series of cases, two cases following

the Supreme Court’s Bell Atlantic versus Twombly decision, the Supreme Court

answered that question by invoking this principle of transsubstantivity, and

saying that in fact, what Bell Atlantic represented was a ratcheting up of

the pleading standard across the board. This is a procedural issue. And what we say about procedure

in one context applies in all the other contexts as well.

And so,

in a pair of cases involving civil rights claims improper imprisonment claims,

discrimination claims, that kind of claim. The court took these stronger and more demanding statements that it

had made about pleading in the very specific context of a conspiracy

to violate the anti-trust statute. It applied the same procedural doctrine

to these civil rights cases, and wound up shutting several litigants, or

potentially shutting several litigants, out of court because of what it viewed,

what the court viewed, as the implausible nature of their allegations at

the very outset of the lawsuit. And this is a very consequential

procedural holding because the pleading standards not only

determine whether you’re going to be able to get into court in the first place,

but if your complaint gets dismissed because you have failed to

satisfy the pleading standards and you can’t rehabilitate your complaint in a

sufficient fashion, that’s your one shot. You get one shot to file a complaint on

a given claim in the civil court system. And so ratcheting up the pleading

standard means that, potentially, litigants are going to be shut out of

court and shut of court permanently.

And this principle of

transsubstantivity winds up producing this very consequential result. Now, there are both good and bad aspects

to this principle of transsubstantivity. The virtue of this principle is that

we want our procedure system to be predictable. We want it to be the case that when

the courts talk about procedure doctrines in one type of lawsuit, that we can

take what they say, we can take the, the holdings and the principles that

they articulate in those cases, and predictably apply them to other

types of cases as well, right? There is value to that kind of

uniformity and predictability. The danger is that the line

between procedure and substance is not always quite so sharp. And if we have a procedural

holding in one particular type of case that really seems powerfully tied

to the substantive law in that case, then is it always clear that this

principle of transsubstantivity should mean that it should apply to all

kinds of other cases as well?

The idea of transsubstantivity,

that is, depends upon a fairly robust understanding of the distinction

between substance and procedure. And Bell Atlantic versus Twombly

is one case that illustrates that, perhaps sometimes, that assumption that

there is this sharp distinction between procedure and substance,

is not always a good assumption. And that applying

transsubstantivity in such a doctrinaire fashion can sometimes

produce negative consequences. That illustration of transsubstantivity

in this relationship to this substance procedure distinction

will provide a great bridge into our next discussion of the second principle,

which is, in fact, this distinction

between procedure and substance. [MUSIC]

Civil Procedure: Part 3

[MUSIC] The second issue that we will discuss

is the distinction between quote, unquote substantive questions and

quote, unquote procedural questions. Now the federal statue that brings

into existence the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, the statue called

the Rules Enabling Act of 1934, contains in the very text of the statute

an apparent requirement that we distinguish between substance and

procedure. The statute specifies that it

authorizes the bringing into existence of these things

the federal rules. And it says that there are rules that

are designed to deal with questions of practice, procedure, and evidence.

And the statute also specifies that these

rules are never supposed to abridge, enlarge, or modify substantive rights.

So right there in the text of the statute

is an apparent requirement that we draw distinction between substance and

procedure. And broadly speaking, that’s a distinction that would seem

to make a fair amount of sense. Substantive questions

are the questions that we might think of as having greater

social policy implications, being the types of questions that

legislators and other types of account, politically accountable figures, ought to

be responsible for carrying into effect. Procedural questions are the types of

questions that are generally involved in the administration of

a civil justice system. And drawing a distinction

between the types of questions that legislature

should address and the types of questions that rulemakers

should address seems quite sensible. And that is, at base, what this substance

procedure distinction is meant to capture.

But it’s not always quite so

easy to draw that distinction. Or at least, to draw it in a way

that makes a lot of sense. And after 75 years of practice under

the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, we have learned that, in fact,

it’s not always quite so easy to draw a sharp line between matters

of procedure and matters of substance. As one example, the pleading standard cases that I

mentioned from the previous section. Those are cases in which

a procedural issue. Speaks in a very direct fashion to

whether people are going to be able to get into court at all. That would seem to have some pretty

significant, maybe even quote, unquote substantive implications to it. And so figuring out when it is that we can

draw a distinction between substance and procedure that is satisfying is

a continuing issue that gets addressed by scholars and by courts in the administration

of our civil justice system. So, the example that I want to discuss to

illustrate this proposition more fully, is the example of class actions.

Class actions are one

of the most powerful, procedural mechanisms in

the modern civil justice system. In the federal system, they are governed

by a rule that gets discussed a lot, Federal Rule’s 23 in our

civil procedure system. And, the modern version of

Federal Rule 23 was brought into being just about 50 years ago in 1966. And, Rule 23 authorizes

a representative lawsuit, a class action in which one or

several individuals come into court with their lawyers, and they say,

we’ve been injured in the following way, a contract has been violated our

financial interests have be affected. We’ve been injured in some fashion, but not only have we been injured, a whole lot

of other people have been injured as well. A whole lot of other people who

are similarly situated to us have been injured in very much the same way. And when litigants come into court and

invoke Rule 23 and seek to initiate a class action, what they say is,

we don’t want to just litigate our claims. We want to litigate the claims

of everybody who’s been hurt in the ways that we’ve been hurt. This is a remarkable proposition

if you think about it. Right? A couple of litigants come

in with their lawyers, and often it’s the lawyers who really

play a much more powerful role in, in guiding the course

of these proceedings. And they say, we want to litigate a set

of claims on behalf of a whole bunch of people whom we’ve never met,

who we have no relationship with. But whom we think we would be adequate

representatives for to adjudicate or to litigate their claims that

are just like the claims of the particular people who come in,

into court to initiate the proceeding.

And the circumstances under which a class

action is permissible, the circumstances under which a court will allow a lawsuit

to proceed as a class action is an issue of major importance in the civil justice

system of the United States today. Among other things, as you can well

imagine, if a defendant, let’s say for example a corporate defendant,

faces the claims of one or a couple or a small handful of injured individuals,

then their exposure. Right?

The overall amount they might have to pay in response to these law suits

is liable to be relatively modest. But if one or a couple or a handful of

individuals can come into court and litigate everybody’s claims,

litigate the claims of a whole class of people who they say have been injured,

suddenly the corporation exposure, the corporation’s potential

damages that they have to pay, is enormously magnified and it becomes

a very very high stakes lawsuit. Class actions serve very

important functions, in that they can enable claims that nobody would

otherwise be able to afford to litigate, to get adjudicated by the court. So if you’ve got one

hundred thousand people. Each one of whom has been injured to

the tune of $50, let’s say because of an improper billing practice from their

cable company or from their cellphone company, no one person is going to be able

to litigate a $50 claim in all likelihood. But, if it’s possible for

a couple of people to come into court, represented by lawyers who are going to

bring those claims on behalf of everybody, then suddenly 100,000 people with $50

claims becomes a $5,000,000 lawsuit, and that’s a lawsuit

that’s worth litigating.

So class actions can have

the effect of allowing claims to get enforced that wouldn’t

otherwise be enforced at all. But the flip side is that class actions

have the potential to create a lot of pressure, maybe even improper

pressure on defendants to settle lawsuits in order to avoid

what might be crippling exposure. And there’s all kinds of other reasons

why class action lawsuits have to be monitored very carefully, because they can

be misused or even abused in various ways.

Okay. So, in New York state, there are a series

of provisions in their state court systems, and in their state legal

framework that address class actions. And in particular, New York brought in to

being its own version of the class action, the modern class action. Several years after the federal

version was brought into being. But when the lawmakers in New York

created their class action system, they took a look at their laws and they

said, you know, we have some statutes in New York where we have penalty provisions,

we have statutory damages. We, we make certain kinds

of remedies available to people on the assumption

that they should get paid, not necessarily based upon how much

they’ve actually been injured. But, they should get paid a, a fixed

amount, which might be a larger amount than the actual injury that they’ve

suffered in order to create a mechanism by which people, individual people,

can actually bring these lawsuits. Or in order to create disincentives for certain kinds of defendants

to engage in bad behavior. And we think these are great. We think these make a lot

of sense in our laws.

But if you can have a class action

in a case involving statutory or penalty damages,

then suddenly you’re going to be magnifying the effects of

these penalties totally out of proportion with what they were intended

to do when they were first enacted. Or at least there’s a danger

that that could happen. And so we in New York are going

to create class actions, we think class actions are a great idea. But we’re going to create a separate

provision of law that says, if you’re dealing with a statute

that confers penalty damages or statutory damages, where there’s this

danger that a class action could magnify the liability

out of all proportion. Then no class actions, unless the actual

statute that creates the penalty or the statutory damages

authorizes class actions. In other words, we’re going to

say if we’ve created statutory or penalty damages,

these types of damages that are really geared towards individual

enforcement and could be misused or, or at least create bad consequences if

they’re the subject of a class action, you can’t have a class action for

that kind of substantive law dispute. Unless we specifically say in the statute

itself that you can have a class action. So that’s how New York geared its class

action system in the state courts.

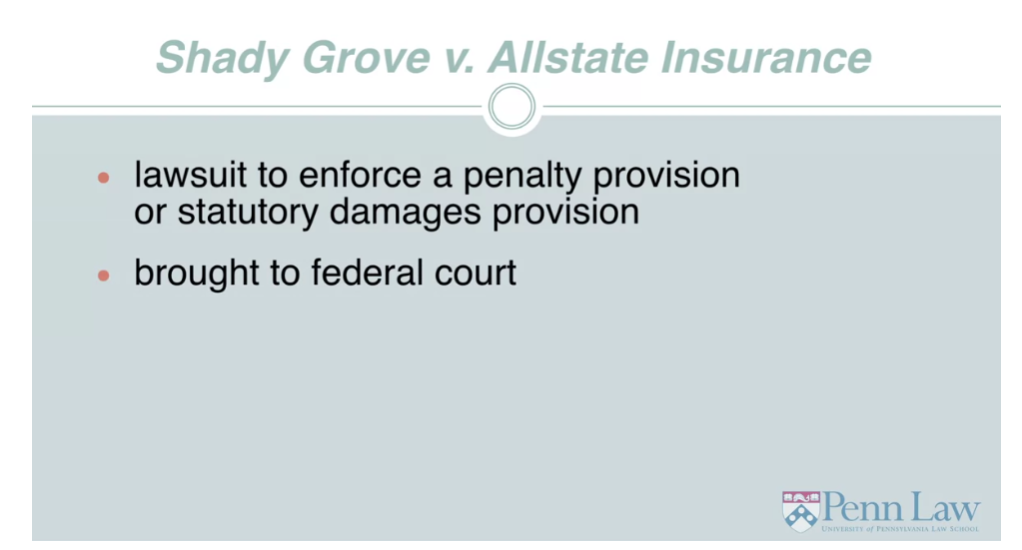

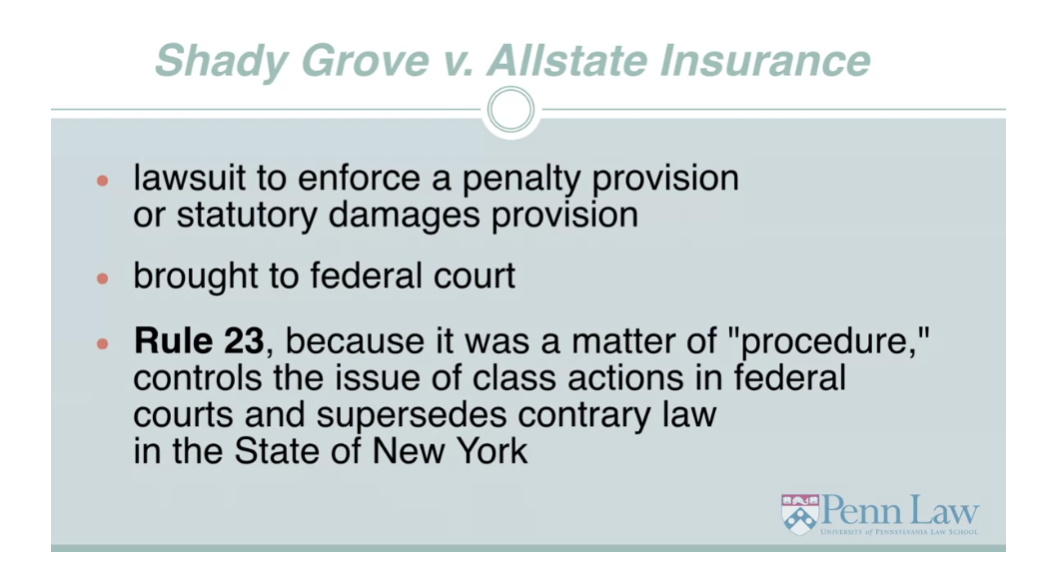

Now, in a lawsuit that recently

came before the Supreme Court, in a case called Shady Grove versus

Allstate Insurance, a question arose. And the question was this. Let’s say that you’re bringing

a lawsuit under New York State law. And let’s say that you’re bringing

that lawsuit to enforce one of these penalty provisions or

one of these statutory damages provisions. But instead of bringing it in

the New York State courts, let’s say you bring it in federal court.

In many ways, the court systems in

our country, the federal courts and the state courts,

operate in parallel with each other. And there are many types of lawsuits,

not all, but many types of lawsuits that could be

brought either in the federal courts or in the state courts, and

this was potentially one of them. And so the plaintiffs took a look at

New York state law, and they said, well, Gee, we can’t have a class

action in New York state court, because New York statutes make it

very clear that this is the type of penalty case where a class

action is not appropriate. But let’s just bring our

lawsuit in federal court. And we can invoke Rule 23. And we can have a class action. Rule 23 doesn’t have any of these limitations that

New York’s provisions have. And we can have our class

action in federal court.

And so the question I presented to

the Supreme Court of the United States, is that possible? Is it possible to bring a lawsuit in

federal court based on a New York claim, where you wouldn’t be able to have a class

action in the courts of New York, but you can have a class

action in federal court, simply by pointing to this provision,

Rule 23? And the case went up to the Supreme Court,

and in a very fractured five to four in some places, six to three in other

places, decision, the court said yes. And the court said, in fact, that Rule 23,

because it was just a matter of quote, unquote procedure, controls the issue of

class action in the federal courts for all purposes and trumps, or, or supersedes,

any contrary law in the state of New York.

And in particular, in response to

the argument from the defendant in that case which was this insurance company,

in response to the argument that there are these serious substantive implications

to having a class action according to this New York Statue, where you couldn’t

have it in the course of New York, and where it looks like New York law says

that a class action shouldn’t happen. What the Supreme Court said was,

but nonetheless, we have decided that class actions

are a matter of quote, unquote, procedure. And that procedural questions are governed

by the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure. And any consequences that it might impose

upon the policies of New York to allow a class action in this kind of case are

merely incidental consequences that don’t change the character of this question as

a quote, unquote procedural question.

Now this is a very controversial opinion. And it’s an opinion that really highlights

what could be at stake, when you draw this distinction between quotes procedure and

quote substance in such sharp and rigid terms, class actions are the biggest

and most important or one of the biggest and most important things

going on in our procedural system today. And in the New York case in particular,

the result of this decision by the Court was to take what was essentially

a $500 lawsuit by an individual and turn it into a $5 million lawsuit

on behalf of an entire class. How can that not have some kind

of substantive implications? Good question. But if it does have substantive

implications, then does that mean that class actions in the federal

court are always problematic or always somehow invalid, because,

after all, the Federal rules of Civil Procedure are, are only supposed

to deal with procedure questions and are not supposed to deal

with questions of substance.

If class actions have substantive

implications in, in every case, then maybe class actions are invalid across the board

under the Rules Enabling Act of 1934. This was the vexing question that

the Court was presented with in this Shady Grove versus

Allstate Insurance case. And in that case, they wound up adopting

a relatively formalistic, in a fairly rigid way of defining this distinction

between procedure and substance. And they allowed a class action to

happen in the federal courts that couldn’t have happened under the courts

of, in the courts of New York and under the laws under New York. And so

following this Shady Grove decision, the law today is that you can have a class

action in the federal courts in a type of claim where you can’t have a class

action in the State courts of New York. And the reason for that somewhat

surprising result is this sharp distinction that the Court has felt the

need to draw between questions of quote, unquote substance and

questions of quote, unquote procedure.

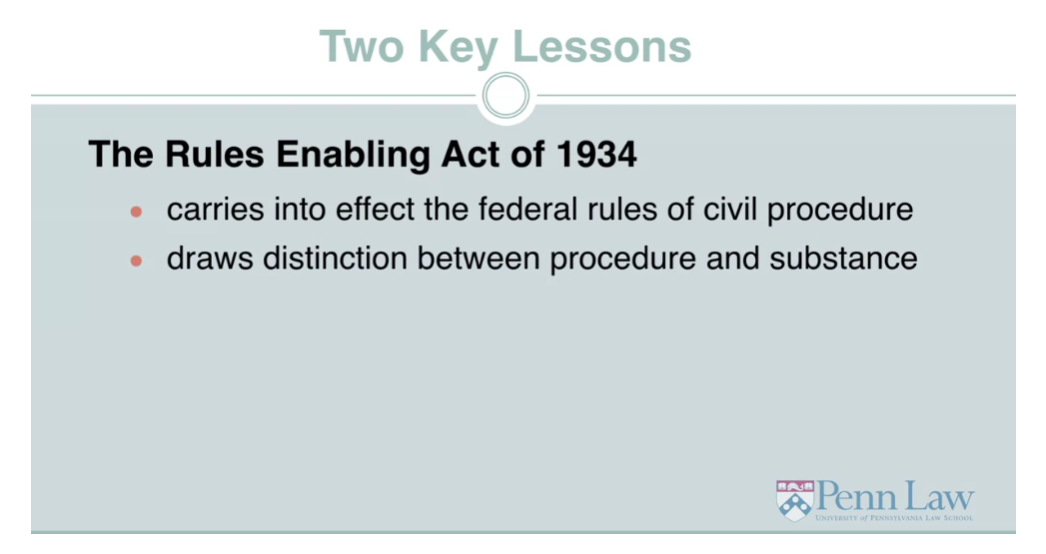

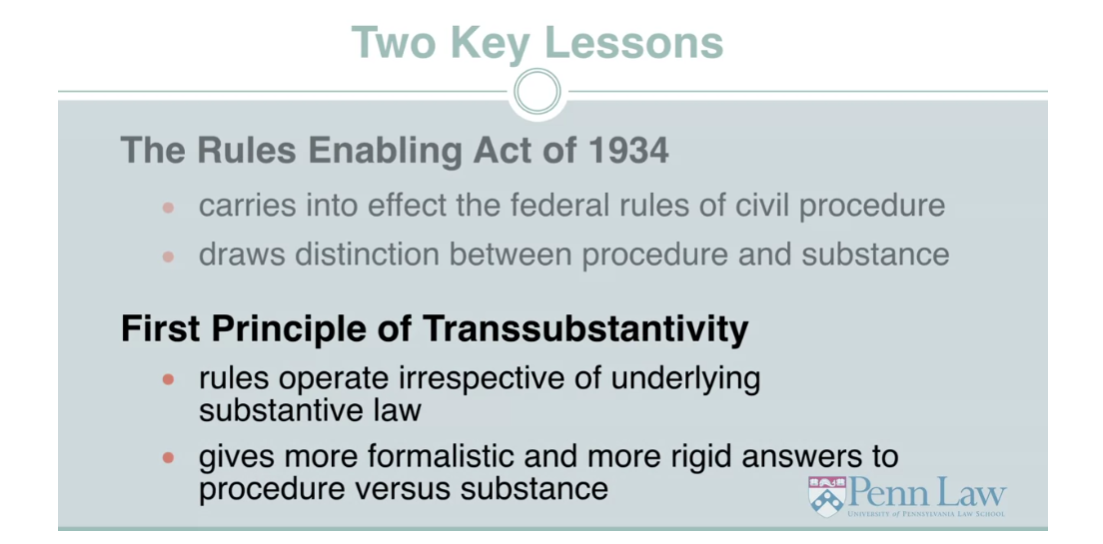

So, there are two lessons I want to focus

on we can, I think take away from this particular grappling with the substance

versus procedure distinction. The first is that it’s a distinction

that we can’t avoid grappling with. The Rules Enabling Act of 1934, that statute that carries into effect

the federal rules of civil procedure, in its very text draws this distinction

between procedure and substance. We have to draw this distinction.

But it is a very difficult distinction

to administer in particular cases. And part of what the Shady Grove decision

illustrates is that a lot can be at stake, and if we approach this question with too

much formalism, with too much rigidity, it can produce answers that don’t seem

to make a lot of sense on the ground. The second lesson goes back to this

First Principle of Transsubstantivity. The idea that the rules are supposed to

operate irrespective of the underlying substantive law, transsubstantivity,

right, invites us I think to give more formalistic and more rigid answers to this

question of procedure versus substance.

Because if you think about it,

one alternative in the Shady Grove case would have been to

say that the type of statute involved in the New York case is one that needs to be

treated differently in a federal class action than other types of statutes might

be treated in different types of lawsuits. That might have produced

a sensible result. But its intention with this

transubsitivity principle, the procedure is not supposed to vary, depending upon the underlying substance

of the legal dispute before the court. And so administering this

distinction between substance and procedure is necessary and

unavoidable, but also very difficult. And operates in some tension with this

important, but, but sometimes excessively applied, principle of transsubstantivity,

which says the procedure is supposed to operate in the same way,

no matter what the underlying law. If procedure is supposed

to operate in the same way, no matter what the underlying law,

that encourages more formalistic or rigid answers to this substance

procedure distinction. And we’ve seen that dynamic

play out many times. [MUSIC]

Civil Procedure: Part 4

[MUSIC] Arbitration is a mechanism by

which litigants can choose to have their disputes resolved,

not in our court systems, but before a private decision maker. Arbitrators are men and women who

are paid professionals, whose job it is to resolve disputes that would

otherwise be heard in the court system, but whom the litigants decide to hire

to resolve their dispute instead. Now why might a litigant want to have a

case heard before an arbitrator instead of before a court? Well broadly speaking,

arbitrators are sometimes less formal. There is the possibility that arbitration

might be less expensive than a lawsuit. Arbitration can produce

a quicker result sometimes. Arbitration carries the promise,

at least, of being more final because the opportunities to appeal

an arbitration decision are fewer.

And so litigants will often get a dispute

that will be completely over at a, at a, a sooner point in the process from, from an arbitrator than would be

true from a civil court system. There are many reasons why, historically, arbitration has been an option that

some litigants have wanted to pursue. And in the United States,

there’s a federal statute, the Federal Arbitration Act, which was enacted in 1925, which grants

a favored status to arbitration. And in particular, what this federal

statute says, is that if people sign a contract in which they agree that if a

dispute arises between them, then they’re going to arbitrate that dispute instead

of litigating it in the courts. Then that contract has to be enforceable

and courts are not allowed to set aside that contract simply because they’re

hostile towards the idea of arbitration.

That they don’t like

the idea of arbitration. Okay. So in recent years, the practice of

arbitration has wound up being a major focus of attention among courts and

commentators for a very specific reason, which is, the capacity of arbitration

to wind up not just being an alternative venue or an alternative

mechanism for disputes to be resolved. But also the capacity of

arbitration to displace some of the more powerful features

of our procedure system. And indeed, in recent years,

the Supreme Court has decided a series of cases that have given defendants, and

in particular corporate defendants, who are the ones who usually draft

contracts, a lot of powerful tools for shielding themselves from certain types

of civil lawsuits, and certain types of powerful civil procedure tools that

might be available in the federal courts. This is actually one of the major issues

that is getting discussed in the field of civil procedure and

dispute resolution today.

And it’s worth taking a moment to spell

out exactly what is at stake here. A lot of the attention on arbitration,

in the last several years, has focused on class actions, and the ways

in which arbitration can be used to prevent plaintiffs from bringing class

actions in certain types of cases. Class actions, that powerful tool that

we discussed in the previous section, are this mechanism by which lots and

lots of claims that might not be affordable to bring on an individual

basis, can be collected together and brought on a representative basis,

all at once, in front of a court. So let’s, imagine that we have

a series of potential claimants, a class of potential claimants, all of

whom have signed a similar contract. It could be a contract with

a credit card company. It could be a contract

with a cell phone company. And they think that they

have a potential claim. Let’s say that the company,

in drafting its contract, has included an arbitration clause. A clause which says,

if you have a dispute with this company, then you agree that you’re going to

resolve that dispute through arbitration, rather than by bringing a lawsuit.

So, let’s then imagine that somebody

believes that they’ve been injured and they believe that the entire

class of people had been injured. The company has engaged in

an improper billing practice and it’s engaged in that improper practice

with respect to everybody who gets a certain service from that company,

right? Classic case where the plaintiff might

come into court and say, I’d like to represent not just myself but an entire

class of people who have been harmed. If the company has put an arbitration

clause into its contract, then the company can respond by saying, you’re

not allowed to bring that case in a court. You have to bring that

court before an arbitrator.

So, a situation like this

would present two questions. First of all, can the defendant

really force this case to be heard in front of an arbitrator instead

of in front of a court? Can the arbitration clause

really be enforced? And more to the point, are there any

limits on the ability of the drafter of that arbitration clause to

compel its enforcement. The second question is, let’s say the case

is heard in front of an arbitrator. Can it be heard as a class, nonetheless? Is there such a thing

as class arbitration? And what are the circumstances under which

there might be a class proceeding in front of an arbitrator, instead of

a class proceeding in front of a court?

In a series of decisions

over the last ten years or so, the Supreme Court has

addressed these questions. And it has addressed these

questions in a way that severely limits the ability of plaintiffs

to bring class action proceedings. And in particular, it gives defendants and

the people who draft contracts, mostly corporate actors who provide services or

perhaps even who employ a lot of people. It gives a lot of tools to

those types of defendants to shield themselves from certain types

of class or, or mass adjudication.

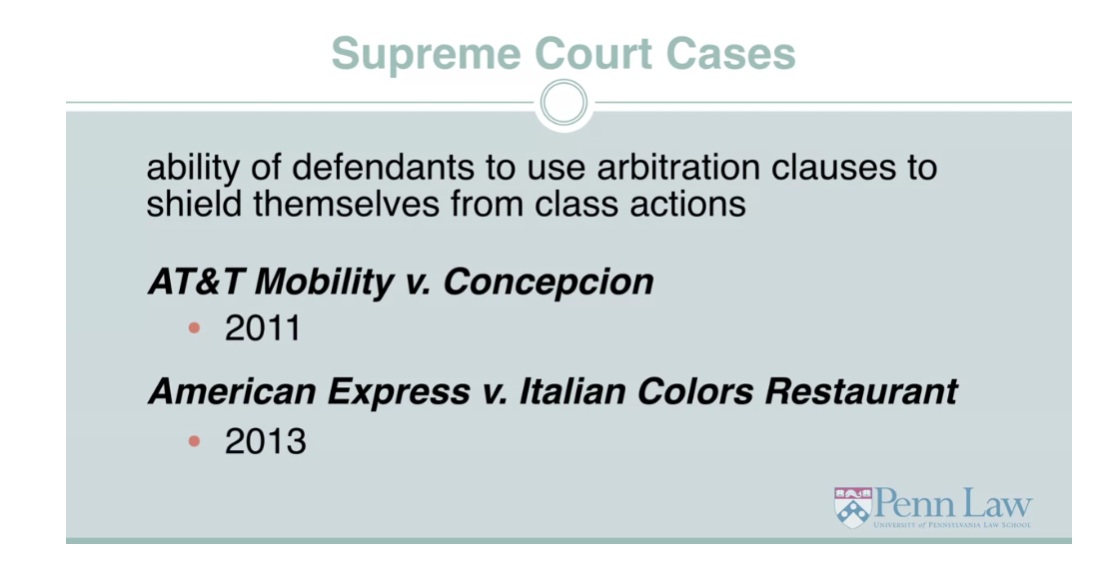

In particular, let’s talk about two cases

that the supreme court has decided, that addressed this question of

the ability of defendants, and in particular corporate actors,

to use arbitration clauses to shield themselves from certain kinds

of class actions or mass disputes. One of them is called AT&T Mobility versus

Concepcion and it was decided in 2011. And the second is called American Express

versus Italian Colors Restaurant, which was decided in 2013.

Both of these were cases in which

the corporate defendant had drafted a contract. In the case of AT&T Mobility,

it was a contract for cell phone services that was drafted for

the company’s customers. In the case of American Express,

it was a merchant agreement that American Express entered into with

certain merchants, like restaurants for example, that specified the terms

on which those restaurants could accept American Express

cards by way of payment. And in both of these contracts, the

company included an arbitration clause, that said that this lawsuit

had to be litigated if at all, as an arbitration rather

than as a lawsuit. And, both of these contracts

were also designed to explicitly prevent class actions. And the arbitration clause not only said,

this case has to be arbitrated, but the arbitration clause also said,

no class-wide arbitration. And in the case of At&T Mobility

versus Concepcion, there were some provisions in the contract

that sought to make it easier for individuals to bring

individual arbitrations. But that made it clear that class-wide

arbitrations were not permitted. In Italian Colors, there were

provisions that not only made it clear that a class action wouldn’t be possible,

but there were also provisions that prevented merchants from banding

together on a more individual basis, and seeking to pool their resources,

and make it more affordable for them collectively to bring a lawsuit

asserting what was, in that case, anti-trust claims, federal anti-trust

claims against American Express.

Both of these lawsuits went

up to the Supreme Court, on the question of whether these

arbitration clauses could be enforced. And in both cases,

the argument was not just a sort of abstract question about the enforceability

of the arbitration clause, but they were questions specifically

about what the practical impact of the arbitration clause would be, on the

ability of people to assert their claims. So in AT&T versus Concepcion, the question was whether in the absence of

a class action, there was going to be any real enforcement under state law against

what the plaintiffs asserted was an improper billing practice

on the part of AT&T Mobility. And in the Italian Colors case, the question was whether there would

be any affordable mechanism at all for these individual merchants to

assert their anti-trust claims. To assert that American Express was

misusing its market power in some way, in defining the terms that

it extracted from merchants, this was the allegation in their,

in their payment relationships.

And there were very good arguments to

the effect, in both of these cases, that if the arbitration clause

was enforced on its terms, that the practical consequence would

be that there either would be very few claims brought, in the AT&T case, or

there might be no claims at all brought, in the Italian Colors case, because

it simply would not be affordable for individuals to assert

these claims on their own.

And in both cases, the Supreme Court held

that under this very powerful statute, or the statute at least that it’s

interpreted in very powerful ways, the Federal Arbitration Act, that the

arbitration clauses had to be enforced. That the corporate defendants

could draft these clauses, which it would offer to people as what’s

often called a contract of adhesion. That is to say, these are the terms on which we’re

willing to do business with you. We’re not going to negotiate

these contract terms.

And you’ve probably signed half

a dozen contracts of adhesion in the past couple of weeks, if you’ve made reservations online,

if you’ve signed up for a gym membership. All of these everyday

activities that we engage in, that involve clicking online or checking

a box or signing a contract, have many, many terms in them that we would never

think about trying to negotiate, and that indeed,

might not be subject to any negotiation. That’s often described as

a contract of adhesion.

And defendants have the ability now,

corporate actors have the ability now, to write these arbitration clauses

that shield them from some of the very powerful procedural mechanisms by which

people who think they’ve been injured, might otherwise be able to

seek to pursue their claims. And the question that was before

the court in the Concepcion case and in the Italian colors case was,

are there any limits on the ability of a corporate defendant to succeed,

to enforce those arbitration clauses, even if what it means is that

the plaintiff is going to be deprived of any practical

opportunity to enforce their claims. And in both cases,

the Supreme Court said, yes. And in, in the Concepcion case,

which was a state law case, the court focused a lot on the ways in

which federal law trumps state law. Federal law in this case being

the Federal Arbitration Act. And the court said, specifically, that

even if the enforcement of an arbitration clause under this federal statute might

mean that certain claims might quote, unquote, fall through the cracks.

But that’s not a basis for

arguing around the mandate of this federal statute as

the Supreme Court interpreted it. The Italian Colors case was

a case in which the claims at issue were federal claims, and so you had two federal statutes potentially

squaring off against each other. The Anti-Trust Statute on the one hand, the Federal Arbitration Act

on the other hand. And so the plaintiffs in

the Italian Colors case said, well our case is different,

there has to be some kind of accommodation between these two

competing federal statutes. The Supreme Court wasn’t buying it and

they said once again, as in Concepcion, that the mandate,

what the court viewed as the mandate of the Federal Arbitration Act, require

this arbitration clause to be enforced. And the court said,

in the Italian Colors case, that the mere fact that a plaintiff

has a claim under a statute like the Anti-Trust Statute,

doesn’t guarantee that the plaintiff will have an affordable procedural path

towards the vindication of that claim. And so even if the arbitration clause

is structured in such a way that, as a practical matter,

it becomes impossible for a plaintiff to pursue her claim,

the mere fact that, as a practical procedural matter,

the claim becomes unaffordable, doesn’t mean that, that other federal

statute, that competing federal statute, has somehow been improperly treated or

improperly served.

Now, this I think once again,

has two important lessons for us. Number one, procedure really matters,

and the mechanisms by which plaintiffs seek to enforce their

claims are sometimes just as important as the definition of their substantive

rights under the applicable law. And, this is a fact that

the people who draft contracts and the people who make major financial

planning understand very well. And so, focusing on how procedure

operates is often just as important for corporate defendants and

indeed for plaintiffs advocates, as well as focusing on the definition

of people’s substantive rights.

The second lesson that I

think this has for us, is the importance of

remembering our history. We started this conversation

with this quote, this famous quote from Karl Llewellyn,

that it is important to read the substantive law courses in law school

through the spectacles of procedure. Because substantive law means

nothing except in terms of what procedure says

that you can make real.

In 2013, we had the Supreme Court

saying something that sounds almost the polar opposite. The Supreme Court’s saying, yes,

you may well have substantive rights, but having a substantive right doesn’t entitle

you to an affordable procedural path for actually vindicating and

enforcing that right. In saying that, the Supreme Court seems,

in some ways, to have forgotten or perhaps even to have rejected the lessons

that gave rise to the federal rules of civil procedure in the first place. The lessons that said that you need to

understand substantive principles through the spectacles of the procedure, because

substance means nothing except in terms of what procedure says

that you can make real. In deciding how to administer

questions of transsubstantivity, how to draw distinctions between substance

and procedure, and when it should be permissible for powerful actors to

opt out of the procedural system, even when it means shielding

themselves from all kinds of liability. I think it’s very important for us to continue viewing the substantive law

through the spectacles of the procedure. The observation that Karl Llewellyn made, way back in 1929, has proven to be

just as true today as it was then. [MUSIC]

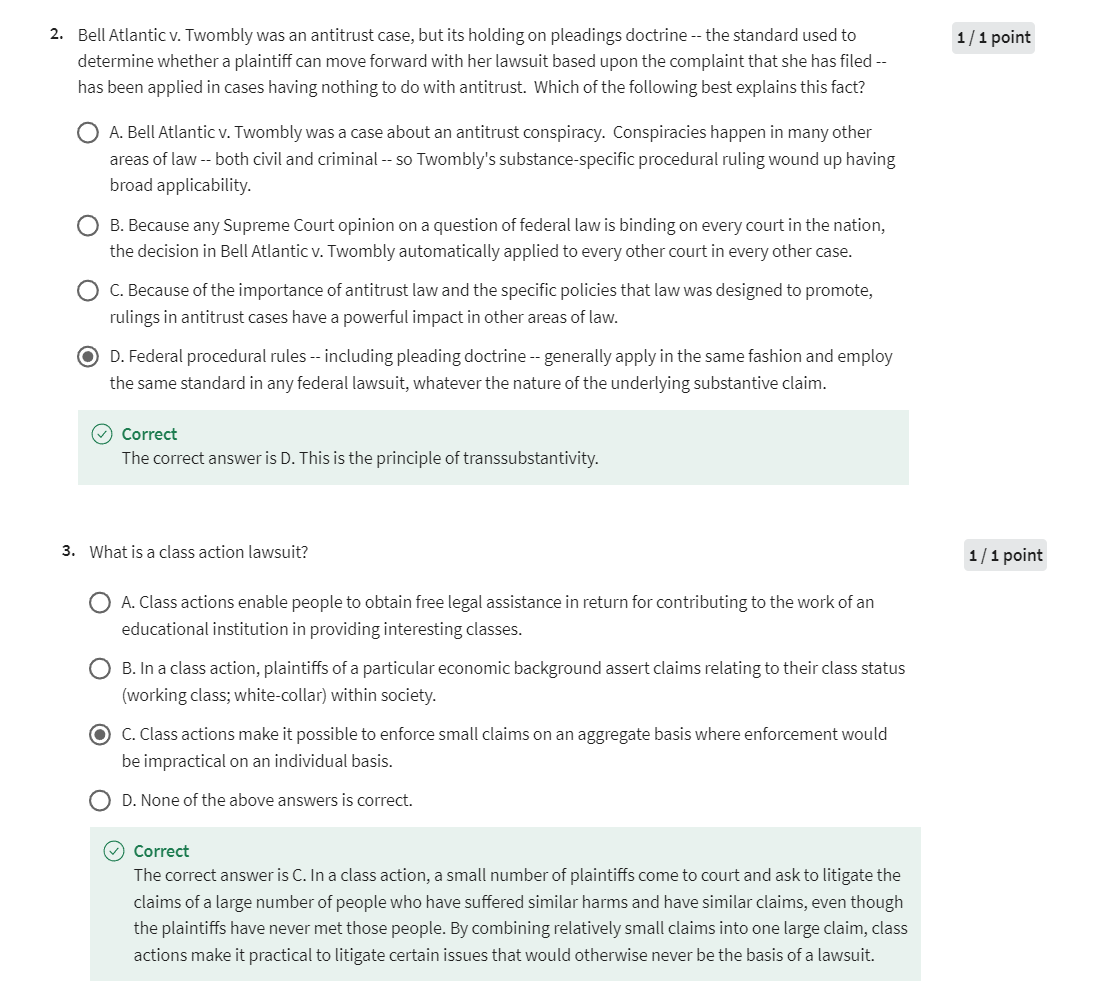

Civil Procedure Quiz

第一题做错了,第二遍做对了

正确答案是 B。《联邦规则》用一套统一适用于整个联邦司法系统的更有效的单一程序,取代了联邦法院以前从各州借鉴的各种低效程序。

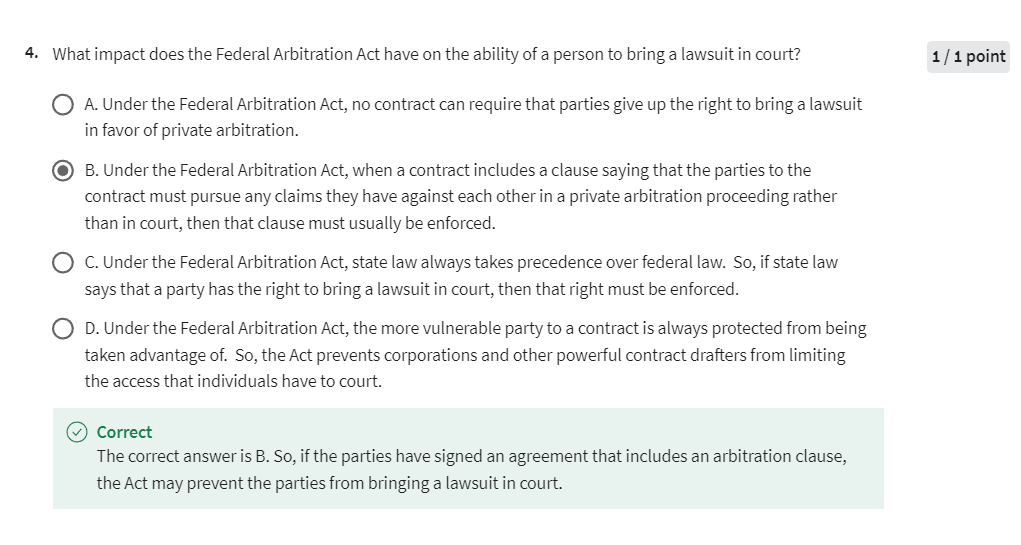

Week 07: Final Exam

第一题改正为:

第八题改正为:

第12题改正为

法律英语

civil procedure:民事诉讼法

litigate: 起诉

litigation:诉讼,起诉,打官司

litigant: 诉讼当事人

civil procedure and complex litigation:民事诉讼和复杂诉讼

entitled to:有权要求,有权获得

injuries that you think you’re entitled to be compensated for:你认为你有权得到赔偿的伤害

transsubstantivity: 跨领域适用性

“Transsubstantivity” 是一个法律术语,用于描述法律概念或原则在不同的法律领域中适用的能力。具体来说,它指的是一个法律概念或原则在一个特定的法律领域中被确认或建立,然后被认为适用于其他法律领域,尽管这些领域可能涉及不同的事实或法律规则。

这种跨越不同法律领域的适用性可能会导致一个法律原则在不同情境下产生相似的效果或解释。这种概念通常出现在法律学术和法律实践中,用于理解和解释法律的一致性和连贯性。

“Procedure” 通常指的是一系列执行特定任务或达到特定目标的步骤或方法。它强调了如何做事情的方式或程序。

“Substance” 则是指事情的实质或内容。在法律上,它通常指的是案件的核心问题、法律原则或事实。

arbitration:仲裁

under the auspices of:在…的帮助(或支持、保护)下

And to use a mechanism called arbitration under the auspices of a very powerful federal statute called the Federal Arbitration Act to find ways to bargain their way around our civil justice system. 并在一项名为《联邦仲裁法》的非常强大的联邦法规的支持下,使用一种名为仲裁的机制来寻找绕过我们民事司法系统的方法。

bells and whistles:铃铛与哨子;附加物;花里胡哨的东西

all the bells and whistles version of the federal rules of civil procedure can sometimes be moderately expensive 《联邦民事诉讼规则》的所有华而不实的版本有时会相当昂贵

viability:美 [vaɪəˈbɪləti] 生存能力,可行性

it focuses us on the relationship between a procedural system and the viability of enforcing a claim:它把我们的重点放在程序制度和强制执行索赔的可行性之间的关系上

allegation: 美 [ˌæləˈɡeɪʃn] 宣称,指控

All you can put in a complaint is allegations, right? I allege that the following things happened. 你只能提出指控,对吗?我声称发生了以下事情。

pleading:诉状

complaint: 诉状

在法律上,“complaint” 可以被称为"诉状"。诉状是民事诉讼程序中原告向法院提交的一份文件,用于提出对被告的诉讼请求和要求。诉状通常包括对案件的基本描述、原告的主张、要求法院采取的行动以及所需的补偿或赔偿等要求。提交诉状后,法院将对其进行审核,并根据诉状内容决定是否受理案件。

conspiracy:阴谋,密谋

in order to establish that there has been a conspiracy to violate the anti-trust statute.

class action: 集体诉讼

在美国法律中,“class actions” 是指一种法律程序,允许一群受到相同或类似损害的个人(被称为原告)以集体的方式提起诉讼。这些个人通常会因为相同的违法行为、产品缺陷、欺诈或其他非法行为而受到损害。在 class actions 中,一个或多个原告代表整个受影响的群体,这个代表称为“类代表”(class representative)。

class actions 的目的是为了有效地处理大规模的法律纠纷,并确保那些受到损害的个人能够获得补偿或其他法律救济。这种法律程序允许法院在一个案件中解决大量相似的索赔,从而提高效率并节省时间和资源。

在 class actions 中,法院通常会对案件进行认证,以确定原告提出的索赔是否适合作为一个类别来处理。如果法院认可了 class actions,并裁定其成立,那么所有符合条件的个人将自动成为该诉讼的成员,除非他们选择退出。如果 class actions 最终成功,那么所有类别成员将根据法院的裁决或达成的和解协议而获得相应的赔偿或补偿。

penalty provision:处罚条款

statutory damage provision:法定损害赔偿条款

enforce one of these penalty provisions or statutory damages provisions: 强制执行这些处罚条款或法定损害赔偿条款之一

supersede:美 [ˌsuːpərˈsiːd] 取代

irrespective of:不管,不考虑

the rules are supposed to operate irrespective of the underlying substantive law, 这些规则的运作应该与基本的实体法无关

hear(heard):审理

Now why might a litigant want to have a case heard before an arbitrator instead of before a court? 现在,为什么诉讼当事人可能希望由仲裁员而不是法庭审理案件呢?

appeal:上诉

wind up:以xxx结束,告终,完成

the capacity of arbitration to wind up not just being an alternative venue or an alternative mechanism for disputes to be resolved:仲裁最终不仅仅成为解决争端的替代场所或替代机制的能力

the practice of arbitration has wound up being a major focus of attention among courts and commentators 仲裁实践已成为法院和评论者关注的焦点

Can the arbitration clause really be enforced? 仲裁条款真的可以执行吗?

后记

截至2024年4月29日15点47分完成Week 6关于民事诉讼法的学习,并且完成Week 7的期末考试。

从2024年4月24日开始学习这门课,历经6天,完成之。起初学习这门课有点吃力,没有学习机器学习、自然语言处理课程那么自然,因为好多法律的术语不是很了解,好在结果是好的,顺利结束。

希望有时间继续在Coursera上学习一些感兴趣的课程。

![AD21技巧[更加便捷的DRC检查][把线框转成Keep-Out Layer板框]](https://img-blog.csdnimg.cn/direct/1b36524dd1054bb29bc78f48a7a7d219.png)

![[Android14] SystemUI的启动](https://img-blog.csdnimg.cn/direct/840460aceb7d488cb2ae8a93c2980a43.png)