文章目录

- Python for Everybody

- 课程简介

- Lists

- A list is a sequence

- Lists are mutable

- Traversing a list

- List operations

- List slices

- List methods

- Deleting elements

- Lists and functions

- Lists and strings

- Parsing lines

- Objects and values

- Aliasing

- List arguments

- Debugging

- Glossary

Python for Everybody

Exploring Data Using Python 3

Dr. Charles R. Severance

课程简介

Python for Everybody 零基础程序设计(Python 入门)

- This course aims to teach everyone the basics of programming computers using Python. 本课程旨在向所有人传授使用 Python 进行计算机编程的基础知识。

- We cover the basics of how one constructs a program from a series of simple instructions in Python. 我们介绍了如何通过 Python 中的一系列简单指令构建程序的基础知识。

- The course has no pre-requisites and avoids all but the simplest mathematics. Anyone with moderate computer experience should be able to master the materials in this course. 该课程没有任何先决条件,除了最简单的数学之外,避免了所有内容。任何具有中等计算机经验的人都应该能够掌握本课程中的材料。

- This course will cover Chapters 1-5 of the textbook “Python for Everybody”. Once a student completes this course, they will be ready to take more advanced programming courses. 本课程将涵盖《Python for Everyday》教科书的第 1-5 章。学生完成本课程后,他们将准备好学习更高级的编程课程。

- This course covers Python 3.

coursera

Python for Everybody 零基础程序设计(Python 入门)

Charles Russell Severance

Clinical Professor

个人主页

Twitter

University of Michigan

课程资源

coursera原版课程视频

coursera原版视频-中英文精校字幕-B站

Dr. Chuck官方翻录版视频-机器翻译字幕-B站

PY4E-课程配套练习

Dr. Chuck Online - 系列课程开源官网

Lists

We learn how to open data files on your computer and read through the files using Python.

A list is a sequence

Like a string, a list is a sequence of values. In a string, the values are characters; in a list, they can be any type. The values in list are called elements or sometimes items.

There are several ways to create a new list; the simplest is to enclose the elements in square brackets (“[” and ”]”):

[10, 20, 30, 40]

['crunchy frog', 'ram bladder', 'lark vomit']

The first example is a list of four integers. The second is a list of three strings. The elements of a list don’t have to be the same type. The following list contains a string, a float, an integer, and (lo!) another list:

['spam', 2.0, 5, [10, 20]]

A list within another list is nested.

A list that contains no elements is called an empty list; you can create one with empty brackets, [].

As you might expect, you can assign list values to variables:

>>> cheeses = ['Cheddar', 'Edam', 'Gouda']

>>> numbers = [17, 123]

>>> empty = []

>>> print(cheeses, numbers, empty)

['Cheddar', 'Edam', 'Gouda'] [17, 123] []

Lists are mutable

The syntax for accessing the elements of a list is the same as for accessing the characters of a string: the bracket operator. The expression inside the brackets specifies the index. Remember that the indices start at 0:

>>> print(cheeses[0])

Cheddar

Unlike strings, lists are mutable because you can change the order of items in a list or reassign an item in a list. When the bracket operator appears on the left side of an assignment, it identifies the element of the list that will be assigned.

>>> numbers = [17, 123]

>>> numbers[1] = 5

>>> print(numbers)

[17, 5]

The one-th element of numbers, which used to be 123, is now 5.

You can think of a list as a relationship between indices and elements. This relationship is called a mapping; each index “maps to” one of the elements.

List indices work the same way as string indices:

- Any integer expression can be used as an index.

- If you try to read or write an element that does not exist, you get an

IndexError. - If an index has a negative value, it counts backward from the end of the list.

Theinoperator also works on lists.

>>> cheeses = ['Cheddar', 'Edam', 'Gouda']

>>> 'Edam' in cheeses

True

>>> 'Brie' in cheeses

False

Traversing a list

The most common way to traverse the elements of a list is with a for loop. The syntax is the same as for strings:

for cheese in cheeses:

print(cheese)

This works well if you only need to read the elements of the list. But if you want to write or update the elements, you need the indices. A common way to do that is to combine the functions range and len:

for i in range(len(numbers)):

numbers[i] = numbers[i] * 2

This loop traverses the list and updates each element. len returns the number of elements in the list. range returns a list of indices from 0 to n − 1, where n is the length of the list. Each time through the loop, i gets the index of the next element. The assignment statement in the body uses i to read the old value of the element and to assign the new value.

A for loop over an empty list never executes the body:

for x in empty:

print('This never happens.')

Although a list can contain another list, the nested list still counts as a single element. The length of this list is four:

['spam', 1, ['Brie', 'Roquefort', 'Pol le Veq'], [1, 2, 3]]

List operations

The + operator concatenates lists:

>>> a = [1, 2, 3]

>>> b = [4, 5, 6]

>>> c = a + b

>>> print(c)

[1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6]

Similarly, the * operator repeats a list a given number of times:

>>> [0] * 4

[0, 0, 0, 0]

>>> [1, 2, 3] * 3

[1, 2, 3, 1, 2, 3, 1, 2, 3]

The first example repeats four times. The second example repeats the list three times.

List slices

The slice operator also works on lists:

>>> t = ['a', 'b', 'c', 'd', 'e', 'f']

>>> t[1:3]

['b', 'c']

>>> t[:4]

['a', 'b', 'c', 'd']

>>> t[3:]

['d', 'e', 'f']

If you omit the first index, the slice starts at the beginning. If you omit the second, the slice goes to the end. So if you omit both, the slice is a copy of the whole list.

>>> t[:]

['a', 'b', 'c', 'd', 'e', 'f']

Since lists are mutable, it is often useful to make a copy before performing operations that fold, spindle, or mutilate lists.

A slice operator on the left side of an assignment can update multiple elements:

>>> t = ['a', 'b', 'c', 'd', 'e', 'f']

>>> t[1:3] = ['x', 'y']

>>> print(t)

['a', 'x', 'y', 'd', 'e', 'f']

List methods

Python provides methods that operate on lists. For example, append adds a new element to the end of a list:

>>> t = ['a', 'b', 'c']

>>> t.append('d')

>>> print(t)

['a', 'b', 'c', 'd']

extend takes a list as an argument and appends all of the elements:

>>> t1 = ['a', 'b', 'c']

>>> t2 = ['d', 'e']

>>> t1.extend(t2)

>>> print(t1)

['a', 'b', 'c', 'd', 'e']

This example leaves t2 unmodified.

sort arranges the elements of the list from low to high:

>>> t = ['d', 'c', 'e', 'b', 'a']

>>> t.sort()

>>> print(t)

['a', 'b', 'c', 'd', 'e']

Most list methods are void; they modify the list and return None. If you accidentally write t = t.sort(), you will be disappointed with the result.

Deleting elements

There are several ways to delete elements from a list. If you know the index of the element you want, you can use pop:

>>> t = ['a', 'b', 'c']

>>> x = t.pop(1)

>>> print(t)

['a', 'c']

>>> print(x)

b

pop modifies the list and returns the element that was removed. If you don’t provide an index, it deletes and returns the last element.

If you don’t need the removed value, you can use the del statement:

>>> t = ['a', 'b', 'c']

>>> del t[1]

>>> print(t)

['a', 'c']

If you know the element you want to remove (but not the index), you can use remove:

>>> t = ['a', 'b', 'c']

>>> t.remove('b')

>>> print(t)

['a', 'c']

The return value from remove is None.

To remove more than one element, you can use del with a slice index:

>>> t = ['a', 'b', 'c', 'd', 'e', 'f']

>>> del t[1:5]

>>> print(t)

['a', 'f']

As usual, the slice selects all the elements up to, but not including, the second index.

Lists and functions

There are a number of built-in functions that can be used on lists that allow you to quickly look through a list without writing your own loops:

>>> nums = [3, 41, 12, 9, 74, 15]

>>> print(len(nums))

6

>>> print(max(nums))

74

>>> print(min(nums))

3

>>> print(sum(nums))

154

>>> print(sum(nums)/len(nums))

25

The sum() function only works when the list elements are numbers. The other functions (max(), len(), etc.) work with lists of strings and other types that can be comparable.

We could rewrite an earlier program that computed the average of a list of numbers entered by the user using a list.

First, the program to compute an average without a list:

total = 0

count = 0

while (True):

inp = input('Enter a number: ')

if inp == 'done': break

value = float(inp)

total = total + value

count = count + 1

average = total / count

print('Average:', average)

# Code: http://www.py4e.com/code3/avenum.py

In this program, we have count and total variables to keep the number and running total of the user’s numbers as we repeatedly prompt the user for a number.

We could simply remember each number as the user entered it and use built-in functions to compute the sum and count at the end.

numlist = list()

while (True):

inp = input('Enter a number: ')

if inp == 'done': break

value = float(inp)

numlist.append(value)

average = sum(numlist) / len(numlist)

print('Average:', average)

# Code: http://www.py4e.com/code3/avelist.py

We make an empty list before the loop starts, and then each time we have a number, we append it to the list. At the end of the program, we simply compute the sum of the numbers in the list and divide it by the count of the numbers in the list to come up with the average.

Lists and strings

A string is a sequence of characters and a list is a sequence of values, but a list of characters is not the same as a string. To convert from a string to a list of characters, you can use list:

>>> s = 'spam'

>>> t = list(s)

>>> print(t)

['s', 'p', 'a', 'm']

Because list is the name of a built-in function, you should avoid using it as a variable name. I also avoid the letter “l” because it looks too much like the number “1”. So that’s why I use “t”.

The list function breaks a string into individual letters. If you want to break a string into words, you can use the split method:

>>> s = 'pining for the fjords'

>>> t = s.split()

>>> print(t)

['pining', 'for', 'the', 'fjords']

>>> print(t[2])

the

Once you have used split to break the string into a list of words, you can use the index operator (square bracket) to look at a particular word in the list.

You can call split with an optional argument called a delimiter that specifies which characters to use as word boundaries. The following example uses a hyphen as a delimiter:

>>> s = 'spam-spam-spam'

>>> delimiter = '-'

>>> s.split(delimiter)

['spam', 'spam', 'spam']

join is the inverse of split. It takes a list of strings and concatenates the elements. join is a string method, so you have to invoke it on the delimiter and pass the list as a parameter:

>>> t = ['pining', 'for', 'the', 'fjords']

>>> delimiter = ' '

>>> delimiter.join(t)

'pining for the fjords'

In this case the delimiter is a space character, so join puts a space between words. To concatenate strings without spaces, you can use the empty string, ““, as a delimiter.

Parsing lines

Usually when we are reading a file we want to do something to the lines other than just printing the whole line. Often we want to find the “interesting lines” and then parse the line to find some interesting part of the line. What if we wanted to print out the day of the week from those lines that start with “From”?

From stephen.marquard@uct.ac.za Sat Jan 5 09:14:16 2008

The split method is very effective when faced with this kind of problem. We can write a small program that looks for lines where the line starts with “From”, split those lines, and then print out the third word in the line:

fhand = open('mbox-short.txt')

for line in fhand:

line = line.rstrip()

if not line.startswith('From '): continue

words = line.split()

print(words[2])

# Code: http://www.py4e.com/code3/search5.py

The program produces the following output:

Sat

Fri

Fri

Fri

...

Later, we will learn increasingly sophisticated techniques for picking the lines to work on and how we pull those lines apart to find the exact bit of information we are looking for.

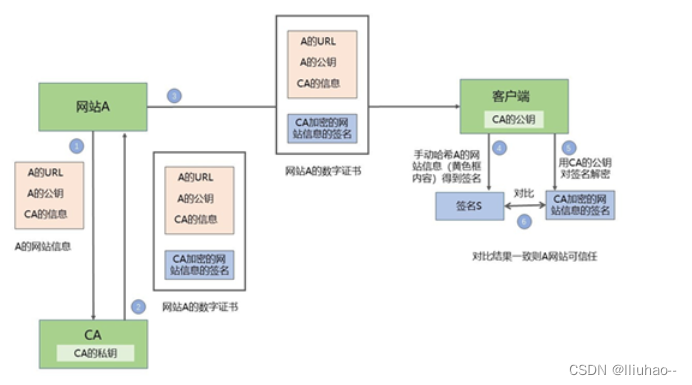

Objects and values

If we execute these assignment statements:

a = 'banana'

b = 'banana'

we know that a and b both refer to a string, but we don’t know whether they refer to the same string. There are two possible states:

Variables and Objects

In one case, a and b refer to two different objects that have the same value. In the second case, they refer to the same object.

To check whether two variables refer to the same object, you can use the is operator.

>>> a = 'banana'

>>> b = 'banana'

>>> a is b

True

In this example, Python only created one string object, and both a and b refer to it.

But when you create two lists, you get two objects:

>>> a = [1, 2, 3]

>>> b = [1, 2, 3]

>>> a is b

False

In this case we would say that the two lists are equivalent, because they have the same elements, but not identical, because they are not the same object. If two objects are identical, they are also equivalent, but if they are equivalent, they are not necessarily identical.

Until now, we have been using “object” and “value” interchangeably, but it is more precise to say that an object has a value. If you execute a = [1,2,3], a refers to a list object whose value is a particular sequence of elements. If another list has the same elements, we would say it has the same value.

Aliasing

If a refers to an object and you assign b = a, then both variables refer to the same object:

>>> a = [1, 2, 3]

>>> b = a

>>> b is a

True

The association of a variable with an object is called a reference. In this example, there are two references to the same object.

An object with more than one reference has more than one name, so we say that the object is aliased.

If the aliased object is mutable, changes made with one alias affect the other:

>>> b[0] = 17

>>> print(a)

[17, 2, 3]

Although this behavior can be useful, it is error-prone. In general, it is safer to avoid aliasing when you are working with mutable objects.

For immutable objects like strings, aliasing is not as much of a problem. In this example:

a = 'banana'

b = 'banana'

it almost never makes a difference whether a and b refer to the same string or not.

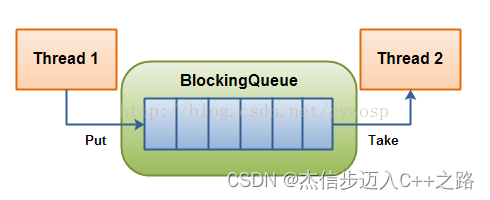

List arguments

When you pass a list to a function, the function gets a reference to the list. If the function modifies a list parameter, the caller sees the change. For example, delete_head removes the first element from a list:

def delete_head(t):

del t[0]

Here’s how it is used:

>>> letters = ['a', 'b', 'c']

>>> delete_head(letters)

>>> print(letters)

['b', 'c']

The parameter t and the variable letters are aliases for the same object.

It is important to distinguish between operations that modify lists and operations that create new lists. For example, the append method modifies a list, but the + operator creates a new list:

>>> t1 = [1, 2]

>>> t2 = t1.append(3)

>>> print(t1)

[1, 2, 3]

>>> print(t2)

None

>>> t3 = t1 + [3]

>>> print(t3)

[1, 2, 3]

>>> t1 is t3

False

This difference is important when you write functions that are supposed to modify lists. For example, this function does not delete the head of a list:

def bad_delete_head(t):

t = t[1:] # WRONG!

The slice operator creates a new list and the assignment makes t refer to it, but none of that has any effect on the list that was passed as an argument.

An alternative is to write a function that creates and returns a new list. For example, tail returns all but the first element of a list:

def tail(t):

return t[1:]

This function leaves the original list unmodified. Here’s how it is used:

>>> letters = ['a', 'b', 'c']

>>> rest = tail(letters)

>>> print(rest)

['b', 'c']

Exercise 1:

Write a function called chop that takes a list and modifies it, removing the first and last elements, and returns None. Then write a function called middle that takes a list and returns a new list that contains all but the first and last elements.

Debugging

Careless use of lists (and other mutable objects) can lead to long hours of debugging. Here are some common pitfalls and ways to avoid them:

- Don’t forget that most list methods modify the argument and return

None. This is the opposite of the string methods, which return a new string and leave the original alone.

If you are used to writing string code like this:

word = word.strip()

It is tempting to write list code like this:

t = t.sort() # WRONG!

Because sort returns None, the next operation you perform with t is likely to fail.

Before using list methods and operators, you should read the documentation carefully and then test them in interactive mode. The methods and operators that lists share with other sequences (like strings) are documented at:

docs.python.org/library/stdtypes.html#common-sequence-operations

The methods and operators that only apply to mutable sequences are documented at:

docs.python.org/library/stdtypes.html#mutable-sequence-types

- Pick an idiom and stick with it.

Part of the problem with lists is that there are too many ways to do things. For example, to remove an element from a list, you can use pop, remove, del, or even a slice assignment.

To add an element, you can use the append method or the + operator. But don’t forget that these are right:

t.append(x)

t = t + [x]

And these are wrong:

t.append([x]) # WRONG!

t = t.append(x) # WRONG!

t + [x] # WRONG!

t = t + x # WRONG!

Try out each of these examples in interactive mode to make sure you understand what they do. Notice that only the last one causes a runtime error; the other three are legal, but they do the wrong thing.

- Make copies to avoid aliasing.

If you want to use a method like sort that modifies the argument, but you need to keep the original list as well, you can make a copy.

orig = t[:]

t.sort()

In this example you could also use the built-in function sorted, which returns a new, sorted list and leaves the original alone. But in that case you should avoid using sorted as a variable name!

Lists,split, and files

When we read and parse files, there are many opportunities to encounter input that can crash our program so it is a good idea to revisit the guardian pattern when it comes writing programs that read through a file and look for a “needle in the haystack”.

Let’s revisit our program that is looking for the day of the week on the from lines of our file:

From stephen.marquard@uct.ac.za Sat Jan 5 09:14:16 2008

Since we are breaking this line into words, we could dispense with the use of startswith and simply look at the first word of the line to determine if we are interested in the line at all. We can use continue to skip lines that don’t have “From” as the first word as follows:

fhand = open('mbox-short.txt')

for line in fhand:

words = line.split()

if words[0] != 'From' : continue

print(words[2])

This looks much simpler and we don’t even need to do the rstrip to remove the newline at the end of the file. But is it better?

python search8.py

Sat

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "search8.py", line 5, in <module>

if words[0] != 'From' : continue

IndexError: list index out of range

It kind of works and we see the day from the first line (Sat), but then the program fails with a traceback error. What went wrong? What messed-up data caused our elegant, clever, and very Pythonic program to fail?

You could stare at it for a long time and puzzle through it or ask someone for help, but the quicker and smarter approach is to add a print statement. The best place to add the print statement is right before the line where the program failed and print out the data that seems to be causing the failure.

Now this approach may generate a lot of lines of output, but at least you will immediately have some clue as to the problem at hand. So we add a print of the variable words right before line five. We even add a prefix “Debug:” to the line so we can keep our regular output separate from our debug output.

for line in fhand:

words = line.split()

print('Debug:', words)

if words[0] != 'From' : continue

print(words[2])

When we run the program, a lot of output scrolls off the screen but at the end, we see our debug output and the traceback so we know what happened just before the traceback.

Debug: ['X-DSPAM-Confidence:', '0.8475']

Debug: ['X-DSPAM-Probability:', '0.0000']

Debug: []

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "search9.py", line 6, in <module>

if words[0] != 'From' : continue

IndexError: list index out of range

Each debug line is printing the list of words which we get when we split the line into words. When the program fails, the list of words is empty []. If we open the file in a text editor and look at the file, at that point it looks as follows:

X-DSPAM-Result: Innocent

X-DSPAM-Processed: Sat Jan 5 09:14:16 2008

X-DSPAM-Confidence: 0.8475

X-DSPAM-Probability: 0.0000

Details: http://source.sakaiproject.org/viewsvn/?view=rev&rev=39772

The error occurs when our program encounters a blank line! Of course there are “zero words” on a blank line. Why didn’t we think of that when we were writing the code? When the code looks for the first word (word[0]) to check to see if it matches “From”, we get an “index out of range” error.

This of course is the perfect place to add some guardian code to avoid checking the first word if the first word is not there. There are many ways to protect this code; we will choose to check the number of words we have before we look at the first word:

fhand = open('mbox-short.txt')

count = 0

for line in fhand:

words = line.split()

# print('Debug:', words)

if len(words) == 0 : continue

if words[0] != 'From' : continue

print(words[2])

First we commented out the debug print statement instead of removing it, in case our modification fails and we need to debug again. Then we added a guardian statement that checks to see if we have zero words, and if so, we use continue to skip to the next line in the file.

We can think of the two continue statements as helping us refine the set of lines which are “interesting” to us and which we want to process some more. A line which has no words is “uninteresting” to us so we skip to the next line. A line which does not have “From” as its first word is uninteresting to us so we skip it.

The program as modified runs successfully, so perhaps it is correct. Our guardian statement does make sure that the words[0] will never fail, but perhaps it is not enough. When we are programming, we must always be thinking, “What might go wrong?”

Exercise 2:

Figure out which line of the above program is still not properly guarded. See if you can construct a text file which causes the program to fail and then modify the program so that the line is properly guarded and test it to make sure it handles your new text file.

Exercise 3:

Rewrite the guardian code in the above example without two if statements. Instead, use a compound logical expression using the or logical operator with a single if statement.

Glossary

aliasing

A circumstance where two or more variables refer to the same object.

delimiter

A character or string used to indicate where a string should be split.

element

One of the values in a list (or other sequence); also called items.

equivalent

Having the same value.

index

An integer value that indicates an element in a list.

identical

Being the same object (which implies equivalence).

list

A sequence of values.

list traversal

The sequential accessing of each element in a list.

nested list

A list that is an element of another list.

object

Something a variable can refer to. An object has a type and a value.

reference

The association between a variable and its value.