个人主页:平行线也会相交

欢迎 点赞👍 收藏✨ 留言✉ 加关注💓本文由 平行线也会相交 原创

收录于专栏【C/C++】

目录

- 文件的打开和关闭

- 文件打开

- "r"

- "w"

- 注意有一个小细节

- 文件的顺序读写

- 字符输入输出函数fgetc和fputc

- fputc

- fgetc

- 补充

- 文本行输入输出函数fgets和fputs

- 格式化输入输出函数

- fprintf

- fscanf

- 注意

- 对比一组函数

- 二进制输入和输出

- fwrite

- fread

- 文件的随机读写

- fseek

- ftell

- rewind

- 文件结束的判定

- 什么是EOF

- feof

- perror

文件的打开和关闭

文件再读写之前应该先打开文件,在使用结束之后应该关闭文件。

在编写程序的时候,再打开文件的同时,都会返回一个FILE*的指针变量指向该文件,也相当于建立了指针和文件的关系。

ANSIC规定使用fopen函数来打开文件,使用fclose来关闭文件。

FILE * fopen(const char * filename, const char * mode);//mode是打开方式

int fclose (FILE * stream);

打开方式如下:

| 文件使用方式 | 含义 | 如果指定文件不存在 |

|---|---|---|

| “r"(只读) | 为了输入数据,打开一个已经存在的文本文件 | 出错 |

| “w”(只写) | 为了输入数据,打开一个文本文件 | 建立一个新的文件 |

| “a”(追加) | 向文本文件尾添加数据 | 出错 |

| “rb”(只读) | 为了输入数据,打开一个二进制文件 | 出错 |

| “wb”(只写) | 为了输出数据打开一个二进制文件 | 建立一个新的文件 |

| “ab”(追加) | 向二进制文件尾添加数据 | 出错 |

| “r+”(读写) | 为了读和写,打开一个文本文件 | 出错 |

| “w+”(读写) | 为了读和写,建立一个新的文件 | 建立一个新的文件 |

| “a+”(读写) | 打开一个文件,在文件尾进行读写 | 建立一个新的文件 |

| “rb++”(读写) | 为了读和写打开一个二进制文件 | 建立一个新的文件 |

| “ab+”(读写) | 打开一个二进制文件,在文件尾进行读和写 | 建立一个新的文件 |

文件打开

#include<stdio.h>

int main()

{

//打开文件test.txt

//相对路径(即相对于当前的代码在哪个路径底下)

//..表示上一级路径

//. 表示当前路径

//fopen("../test.txt","r");

//fopen("../../test.txt","r");

//fopen("test.txt","r");

//绝对路径的写法

//fopen("D:\\vs\code\\101\\C语言-文件操作\\C-文件操作(1)-22-12-1\\test.txt", "r");

return 0;

}

“r”

#include<stdio.h>

#include<errno.h>

#include<string.h>

int main()

{

FILE* pf = fopen("test.txt", "r");

if (pf == NULL)

{

{

printf("%s", strerror(errno));

return 0;

}

}

//来到这里就说明打开成功了

//读文件

//关闭文件

fclose(pf);//pf的类型就是FILE*

//fclose就是把文件关闭掉,把FILE这个结构体所指向的文件关闭掉,把这个资源释放掉

//但是此时pf并没有置成空指针,对于fclose(pf)属于值传递,并没有改变pf

//所以我们就需要把pf置成空指针

pf = NULL;

return 0;

}

我们发现其实并没有成功打开文件,原因就是No such file or directory,即没有这个文件或者文件夹。

我们在前面的表格中可以知道,"r"(只读)如果指定文件不存在的话会出错。

所以我们需要创建test.txt文件之后再来运行程序:

此时我们来运行程序:

屏幕上什么都没有显示就说明打开文件成功了。

“w”

我们先把刚刚创建的test.txt文件删除掉。

因为如果以"w"(只写)的方式来打开文件时,如果指定文件不存在,会新建一个文件。

现在用只写的方式来打开文件:

说明程序打开成功了,我们再来看一看到底有没有创建test.txt文件。

这里的确创建了一个新的文件,在这个路径底下就自动生成test.txt文件。

注意有一个小细节

现在我们给test.txt文件中放入"abcdef",即:

现在我们来运行程序:

当我们再次查看test.txt文件时发现文件是空的。

那为什么会出现这种情况呢?原因是:我们通过"w"(只写)来打开文件时,会新建一个文件出来,那么旧的那个、先前的那个文件里的内容就销毁掉了。即指定的文件存在与否都会新建一个文件。

文件的顺序读写

| 功能 | 函数名 | 适用于 |

|---|---|---|

| 字符输入函数 | fgetc | 所有输入流 |

| 字符输出函数 | fputc | 所有输出流 |

| 文本行输入函数 | fgets | 所有输入流 |

| 文本行输出函数 | fputs | 所有输出流 |

| 格式化输入函数 | fscanf | 所有输入流 |

| 格式化输出函数 | fprintf | 所有输出流 |

| 二进制输入 | fread | 文件 |

| 二级制输出 | fwrite | 文件 |

字符输入输出函数fgetc和fputc

fputc

#include<stdio.h>

#include<string.h>

#include<errno.h>

int main()

{

FILE* pfwrite = fopen("test.txt", "w");//pfwrite所指向的流是文件输出流,即我们要向文件里面写东西

if (pfwrite == NULL)

{

printf("%s\n", strerror(errno));

}

//写文件

fputc('h', pfwrite);

fputc('e', pfwrite);

fputc('l', pfwrite);

fputc('l', pfwrite);

fputc('o', pfwrite);

//关闭文件

fclose(pfwrite);

pfwrite = NULL;

return 0;

}

fgetc

//fgetc

#include<stdio.h>

#include<string.h>

#include<errno.h>

int main()

{

FILE* pfread = fopen("test.txt", "r");//pfread所指向的流为输入流,叫文件输入流,即我们可以从文件中去读取信息

if (pfread == NULL)

{

printf("%s\n", strerror(errno));

}

//读文件

printf("%c", fgetc(pfread));

printf("%c", fgetc(pfread));

printf("%c", fgetc(pfread));

printf("%c", fgetc(pfread));

printf("%c", fgetc(pfread));

//关闭文件

fclose(pfread);

pfread = NULL;

return 0;

}

其实我们也可以这样写:

//fgetc

#include<stdio.h>

#include<string.h>

#include<errno.h>

int main()

{

FILE* pfread = fopen("test.txt", "r");

if (pfread == NULL)

{

printf("%s\n", strerror(errno));

}

//读文件

int ch = fgetc(pfread);

printf("%c", ch);

ch = fgetc(pfread);

printf("%c", ch);

ch = fgetc(pfread);

printf("%c", ch);

ch = fgetc(pfread);

printf("%c", ch);

ch = fgetc(pfread);

printf("%c", ch);

//关闭文件

fclose(pfread);

pfread = NULL;

return 0;

}

结果其实都一样的。

注意事项:以"r"(只读)的方式打开文件时必须确保文件已存在。

在这里之所以可以把hello打印出来是因为已存在的test.txt文件中已经有hello。

补充

我们平时从键盘输入,又或者输出到屏幕。其中键盘和屏幕都是外部设备,我们就可以做到从外部设备读取信息,也可以做到把信息写到外部设备上去。

值得注意的是,我们把我们下信息从键盘上读和我们把信息写到屏幕上时,不需要向文件一样需要打开和关闭文件;当我们把我们下信息从键盘上读和我们把信息写到屏幕上时从来没有说打开键盘或者关闭键盘,又或者打开屏幕、关闭屏幕。

键盘-标准输入设备-stdin

屏幕-标准输出设备-stdout

是一个程序默认打开的两个流设备

当程序执行起来时,会默认打开三个流,即键盘,屏幕,stderr。这三个流的类型都是FILE*。

stdin(标准输入设备)FILE*

stdout(标准输出设备)FILE*

stderrFILE*

而fgetc和fputc均是适用于所有流的,既包括文件流,又包括标准输入流和标准输出流。

举例:

#include<stdio.h>

int main()

{

int ch = fgetc(stdin);

fputc(ch, stdout);

return 0;

}

这个时候我们就发现fgetc可以从标准输入流里面去读取信息,fputc也可以写到标准输出流里面去。即从键盘上读然后输出到屏幕上去。

文本行输入输出函数fgets和fputs

//fgets

#include<stdio.h>

int main()

{

char buf[1024] = { 0 };

FILE* pf = fopen("test.txt", "r");

if (pf == NULL)

{

return 0;

}

fgets(buf, 1024, pf);

printf("%s\n", buf);

fclose(pf);

pf = NULL;

return 0;

}

如果你观察仔细就是发现程序运行的结果多了一个空行。

倘若我把printf("%s\n", buf);中的\n去掉,变成printf("%s", buf);我们再来看一下运行结果:

这里需要我们注意的是这里printf在打印数组buf的时候,这里本身就拥有一个换行。

现在我们来看这段代码:

在这之前我把test.txt文件中的内容换成了这个,即:

//fgets

#include<stdio.h>

int main()

{

char buf[1024] = { 0 };

FILE* pf = fopen("test.txt", "r");

if (pf == NULL)

{

return 0;

}

fgets(buf, 1024, pf);

printf("%s", buf);

fgets(buf, 1024, pf);

printf("%s", buf);

fclose(pf);

pf = NULL;

return 0;

}

结果是这样的:

现在我们来看puts:

//puts

#include<stdio.h>

int main()

{

char buf[1024] = { 0 };

FILE* pf = fopen("test.txt", "r");

if (pf == NULL)

{

return 0;

}

fgets(buf, 1024, pf);

puts(buf);

fgets(buf, 1024, pf);

puts(buf);

fclose(pf);

pf = NULL;

return 0;

}

现在来看fputs:

//fputs

#include<stdio.h>

int main()

{

char buf[1024] = { 0 };

FILE* pf = fopen("test.txt", "w");

if (pf == NULL)

{

return 0;

}

//写文件

fputs("hello\n", pf);

fputs("world\n", pf);

fclose(pf);

pf = NULL;

return 0;

}

我们知道fgets适用于所有输入流和fputs适用于所有输出流,所以请看:

//fgets和fputs

#include<stdio.h>

int main()

{

//从键盘读取一行文本信息

char buf[1024] = { 0 };

fgets(buf, 1024, stdin);//从标准输入流读取

fputs(buf, stdout);//从标准输出流读取

return 0;

}

//fgets和fputs

#include<stdio.h>

int main()

{

//从键盘读取一行文本信息

char buf[1024] = { 0 };

//fgets(buf, 1024, stdin);//从标准输入流读取

//fputs(buf, stdout);//从标准输出流读取

//上述写法等价于下面这种写法

gets(buf);

puts(buf);

return 0;

}

格式化输入输出函数

我们刚刚读取的都是字符串,那现在我们能不能把一些有格式的一些数据写到文件里面去。就比如说结构体

fprintf

//fprintf:可以把格式化的信息放到文件中去

struct S

{

int n;

float score;

char arr[10];

};

#include<stdio.h>

int main()

{

struct S s = { 100,3.14f,"hello" };

FILE* pf = fopen("test.txt", "w");

if (pf == NULL)

{

return 0;

}

//格式化的形式写文件

fprintf(pf, "%d %f %s", s.n, s.score, s.arr);

fclose(pf);

return 0;

}

fscanf

刚刚我们通过fprintf把格式化的信息放进文件中去了。那现在我们也可以通过fscanf把它拿出来。

//fscanf:可以把信息从文件中拿出来

struct S

{

int n;

float score;

char arr[10];

};

#include<stdio.h>

int main()

{

struct S s = { 0 };

FILE* pf = fopen("test.txt", "r");

if (pf == NULL)

{

return 0;

}

//格式化的输入数据

fscanf(pf, "%d %f %s", &s.n, &s.score, s.arr);

printf("%d %f %s\n", s.n, s.score, s.arr);

fclose(pf);

pf = NULL;

return 0;

}

现在我们已经通过格式化输入输出函数按照某一种格式来把数据写进去。当然这种格式可以是我们想要的某一种格式,我们完全可以做到想怎么把数据放进去就可以怎么把数据放进去。

注意

注意:格式化输入输出函数同样适用于所有输入流(fscanf)和所有输出流(fprintf)。

struct S

{

int n;

float score;

char arr[10];

};

#include<stdio.h>

int main()

{

struct S s = { 0 };

fscanf(stdin, "%d %f %s", &(s.n), &(s.score), s.arr);//从标准输入流-即从键盘上获取信息

fprintf(stdout, "%d %f %s", s.n, s.score, s.arr);

return 0;

}

对比一组函数

对比一组函数:

scanf/fscanf/sscanf

printf/fprintf/sprintf

struct S

{

int n;

float score;

char arr[10];

};

#include<stdio.h>

int main()

{

struct S s = { 100,3.14f,"abcdef" };

//假设我们想把s里面的数据转换为字符串

char buf[1024] = { 0 };

sprintf(buf, "%d %f %s", s.n, s.score, s.arr);

//sprintf函数有能力把结构体中的数据转换为字符串

printf("%s", buf);

return 0;

}

注意:这里打印出来我们看到的100已经不是100了,而是100转换为字符串的'1''0''0'。

对于sprintf,我们已经看到sprintf函数的确有能力把结构体中的数据转换为字符串。

我们当然也可以从buf数组中提出来一个结构体数据。

请看:

struct S

{

int n;

float score;

char arr[10];

};

#include<stdio.h>

int main()

{

struct S s = { 100,3.14f,"abcdef" };

struct S tmp = { 0 };

char buf[1024] = { 0 };

//把格式化的数据转换成字符串存储到buf

sprintf(buf, "%d %f %s", s.n, s.score, s.arr);

//printf("%s", buf);

//从buf中读取格式化的数据到tmp

sscanf(buf, "%d %f %s", &(tmp.n), &(tmp.score), tmp.arr);

printf("%d %f %s\n", tmp.n, tmp.score, tmp.arr);

return 0;

}

二进制输入和输出

fwrite

struct S

{

char name[20];

int age;

double score;

};

#include<stdio.h>

int main()

{

struct S s = { "张三",20,59 };

FILE* pf = fopen("test.txt", "wb");

if (pf == NULL)

{

return 0;

}

//二进制的形式写文件

fwrite(&s, sizeof(struct S), 1, pf);

fclose(pf);

pf = NULL;

return 0;

}

struct S

{

char name[20];

int age;

double score;

};

#include<stdio.h>

int main()

{

struct S s = { "张三",20,59 };

FILE* pf = fopen("test.txt", "wb");

if (pf == NULL)

{

return 0;

}

//二进制的形式写文件

fwrite(&s, sizeof(struct S), 1, pf);

fclose(pf);

pf = NULL;

return 0;

}

发现test.txt文件中的后半部分是乱码。原因就是因为我们是以二进制的方式把数据放进文件的。

尽管我们肉眼看不懂二进制形式的文件,但是没关系,如果我们读文件中的信息是应该是可以读出来的。

fread

我们刚刚通过fwrite已经把数据以二进制的方式放进文件中去了,这个时候我们怎么读取文件呢?

//fread

struct S

{

char name[20];

int age;

double score;

};

#include<stdio.h>

int main()

{

//struct S s = { "张三",20,59.5 };

struct S tmp = { 0 };

FILE* pf = fopen("test.txt", "rb");

if (pf == NULL)

{

return 0;

}

//二进制的形式读文件

fread(&tmp, sizeof(struct S), 1, pf);

printf("%s %d %lf\n", tmp.name, tmp.age, tmp.score);

fclose(pf);

pf = NULL;

return 0;

}

文件的随机读写

前面我们学习的是文件的顺序读写,现在我们来介绍一下文件的随机读写。

那什么是文件的随机读写呢?

我们使用fopen打开一个文件可以得到一个文件指针,这个文件指针也会被用于读写文件的时候。我们在读取一个文件的时候,文件指针指向下一个我们要读取的字符(一开始指向第一个字符),每当我们调用一次读取函数时,如 fgetc/fgets,这个文件指针就会向后移动一个或者多个单位。

fseek

//fseek

#include<stdio.h>

int main()

{

FILE* pf = fopen("test.txt", "r");

if (pf == NULL)

{

return 0;

}

//定位文件指针

fseek(pf, 2, SEEK_CUR);

//读取文件

int ch = fgetc(pf);

printf("%c\n", ch);

fclose(pf);

pf = NULL;

return 0;

}

ftell

返回文件指针相对于起始位置的偏移量。

例如:

//fseek

#include<stdio.h>

int main()

{

FILE* pf = fopen("test.txt", "r");

if (pf == NULL)

{

return 0;

}

int pos = ftell(pf);//ftell返回文件指针相对于起始位值的偏移量

printf("%d\n", pos);

fclose(pf);

pf = NULL;

return 0;

}

默认打开时文件指针位于起始位置,此时相对于起始偏移量为0。

来看下一个代码:

rewind

让文件指针的位置回到文件的起始位置

void rewind( FILE * stream);

#include<stdio.h>

int main()

{

FILE* pf = fopen("test.txt", "r");

if (pf == NULL)

{

return 0;

}

int ch = fgetc(pf);

printf("%c\n", ch);

rewind(pf);

ch = fgetc(pf);

printf("%c\n", ch);

fclose(pf);

pf = NULL;

return 0;

}

文件结束的判定

首先我们先要了解EOF是什么?

什么是EOF

当我们打开一个文件而里面什么都没有的时候:

我们第一次读到的就是EOF

#include<stdio.h>

int main()

{

//EOF - end of file - 文件结束标志

FILE* pf = fopen("test.txt", "r");

if (pf == NULL)

{

return 0;

}

int ch = fgetc(pf);

printf("%d", ch);

fclose(pf);

pf=NULL;

return 0;

}

feof

关于feof函数经常会被错误的使用。

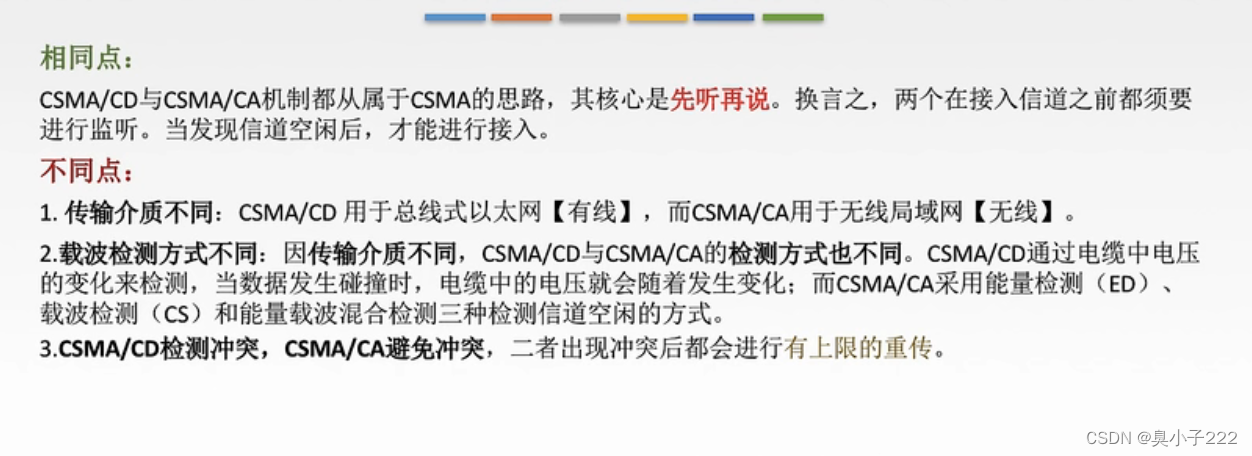

请牢记:在文件读取过程中,不能使用feof函数的返回值直接用来判定文件的是否结束。而是应用于当文件读取结束的时候,判断到底是读取失败结束,还时遇到文件尾结束。

判断文件是否读取结束方法如下:

1.文本文件读取是否结束,判断返回值是否为EOF(fget),或者NULL(fgets)

例如:

- fgetc判断是否为EOF

- fgets判断返回值是否为NULL

2.二进制文件的读取结束判断,判断返回值是否小于实际要读的个数。

例如:

- fread判断返回值是否小于实际要读的个数。

perror

//perror

#include<stdio.h>

int main()

{

//sterror - 把错误码对应的错误信息的字符串地址返回

//printf("%s\n", strerror(erron));

//perror

FILE* pf = fopen("test2.txt", "r");

if (pf == NULL)

{

perror("hehe");

return 0;

}

//读文件

fclose(pf);

pf = NULL;

return 0;

}

函数perror直接会把你放过来的字符串先打印出来,打印一个:,打印一个空格,再把前面发生这个错误的时候,错误码所对应的错误信息打印到后面去。

所以,函数perror与函数strerror相比会更加简单,因为perror函数不需要引用头文件,它自动会把errno,此时此刻被设置的errno里面的值所对应的错误信息打印出来,同时也更加直观。

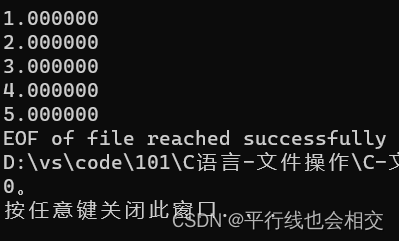

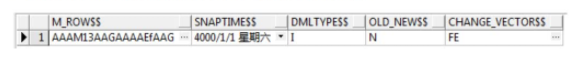

下面才是正确的使用实例:

请务必注意下面这幅图:

结合这段代码:

#include<stdio.h>

int main()

{

int c;//注意:int,非char,要求处理EOF

FILE* pf = fopen("test.txt", "r");

if (!pf)

{

perror("File opening failed");

return -1;

}

//fgetc 当读取失败的时候或者遇到文件结束的时候,都会返回EOF

while ((c = fgetc(pf)) != EOF)

{

putchar(c);

}

//判断是什么原因结束的

if (ferror(pf))

{

puts("I/0 error when reading");

}

else if (feof(pf))

{

puts("EOF of file reached successfully");

}

fclose(pf);

return 0;

}

//二进制文件的例子

#include<stdio.h>

enum

{

SIZE = 5

};

int main()

{

double a[SIZE] = { 1.0,2.0,3.0,4.0,5.0 };

double b = 0.0;

size_t ret_code = 0;

FILE* pf = fopen("test.txt", "wb");//必须用二进制格式

fwrite(a, sizeof(*a), SIZE, pf);//写double的数组

fclose(pf);

pf = fopen("test.txt", "rb");

//读double的数组

while ((ret_code - fread(&b, sizeof(double), 1, pf)) >= 1)

{

printf("%lf\n", b);

}

if (feof(pf))

{

printf("EOF of file reached successfully");

}

else if (ferror(pf))

{

perror("Error reading test.txt");

}

fclose(pf);

pf = NULL;

return 0;

}

以上两段代码请务必记住并理解。

好了😚,C语言文件的操作就到这里吧。这块内容确实比较杂,函数的确好多好多😓。但全是满满的干货啊,这块内容大家一定要多上机实践,相信只要掌握了这块内容对自身C语言水平的提高就又上升到了一个档次。

感谢各位了!!!💕

![[附源码]Python计算机毕业设计高校学生管理系统Django(程序+LW)](https://img-blog.csdnimg.cn/1b20d5c2e061491fb237e428fc269450.png)