前言

这是前几天偶然看到的一篇硬核推文。作者一口气分了 12 个主题探讨了 JavaScript 在优化时应该注意的要点,读后深受启发。由于篇幅较长,分两篇发表。本篇为上篇。

文章目录

- Optimizing Javascript for fun and for profit

- 0. Avoid work

- 1. Avoid string comparisons

- About benchmarks

- 2. Avoid different shapes

- A note on terminology

- What the eff should I do about this?

- Number representation

- 3. Avoid array/object methods

- 4. Avoid indirection

- 5. Avoid cache misses

- 5.1 Prefetching

- What the eff should I do about this?

- 5.2 Caching in L1/2/3

- What the eff should I do about this?

- About immutable data structures

- About the { ...spread } operator

Optimizing Javascript for fun and for profit

by romgrk

I often feel like javascript code in general runs much slower than it could, simply because it’s not optimized properly. Here is a summary of common optimization techniques I’ve found useful. Note that the tradeoff for performance is often readability, so the question of when to go for performance versus readability is a question left to the reader. I’ll also note that talking about optimization necessarily requires talking about benchmarking. Micro-optimizing a function for hours to have it run 100x faster is meaningless if the function only represented a fraction of the actual overall runtime to start with. If one is optimizing, the first and most important step is benchmarking. I’ll cover the topic in the later points. Be also aware that micro-benchmarks are often flawed, and that may include those presented here. I’ve done my best to avoid those traps, but don’t blindly apply any of the points presented here without benchmarking.

I have included runnable examples for all cases where it’s possible. They show by default the results I got on my machine (brave 122 on archlinux) but you can run them yourself. As much as I hate to say it, Firefox has fallen a bit behind in the optimization game, and represents a very small fraction of the traffic for now, so I don’t recommend using the results you’d get on Firefox as useful indicators.

0. Avoid work

This might sound evident, but it needs to be here because there can’t be another first step to optimization: if you’re trying to optimize, you should first look into avoiding work. This includes concepts like memoization, laziness and incremental computation. This would be applied differently depending on the context. In React, for example, that would mean applying memo(), useMemo() and other applicable primitives.

1. Avoid string comparisons

Javascript makes it easy to hide the real cost of string comparisons. If you need to compare strings in C, you’d use the strcmp(a, b) function. Javascript uses === instead, so you don’t see the strcmp. But it’s there, and a string comparison will usually (but not always) require comparing each of the characters in the string with the ones in the other string; string comparison is O(n). One common JavaScript pattern to avoid is strings-as-enums. But with the advent of TypeScript this should be easily avoidable, as enums are integers by default.

// No

enum Position {

TOP = 'TOP',

BOTTOM = 'BOTTOM',

}

// Yeppers

enum Position {

TOP, // = 0

BOTTOM, // = 1

}

Here is a comparison of the costs:

// 1. string compare

const Position = {

TOP: 'TOP',

BOTTOM: 'BOTTOM',

}

let _ = 0

for (let i = 0; i < 1000000; i++) {

let current = i % 2 === 0 ?

Position.TOP : Position.BOTTOM

if (current === Position.TOP)

_ += 1

}

// 2. int compare

const Position = {

TOP: 0,

BOTTOM: 1,

}

let _ = 0

for (let i = 0; i < 1000000; i++) {

let current = i % 2 === 0 ?

Position.TOP : Position.BOTTOM

if (current === Position.TOP)

_ += 1

}

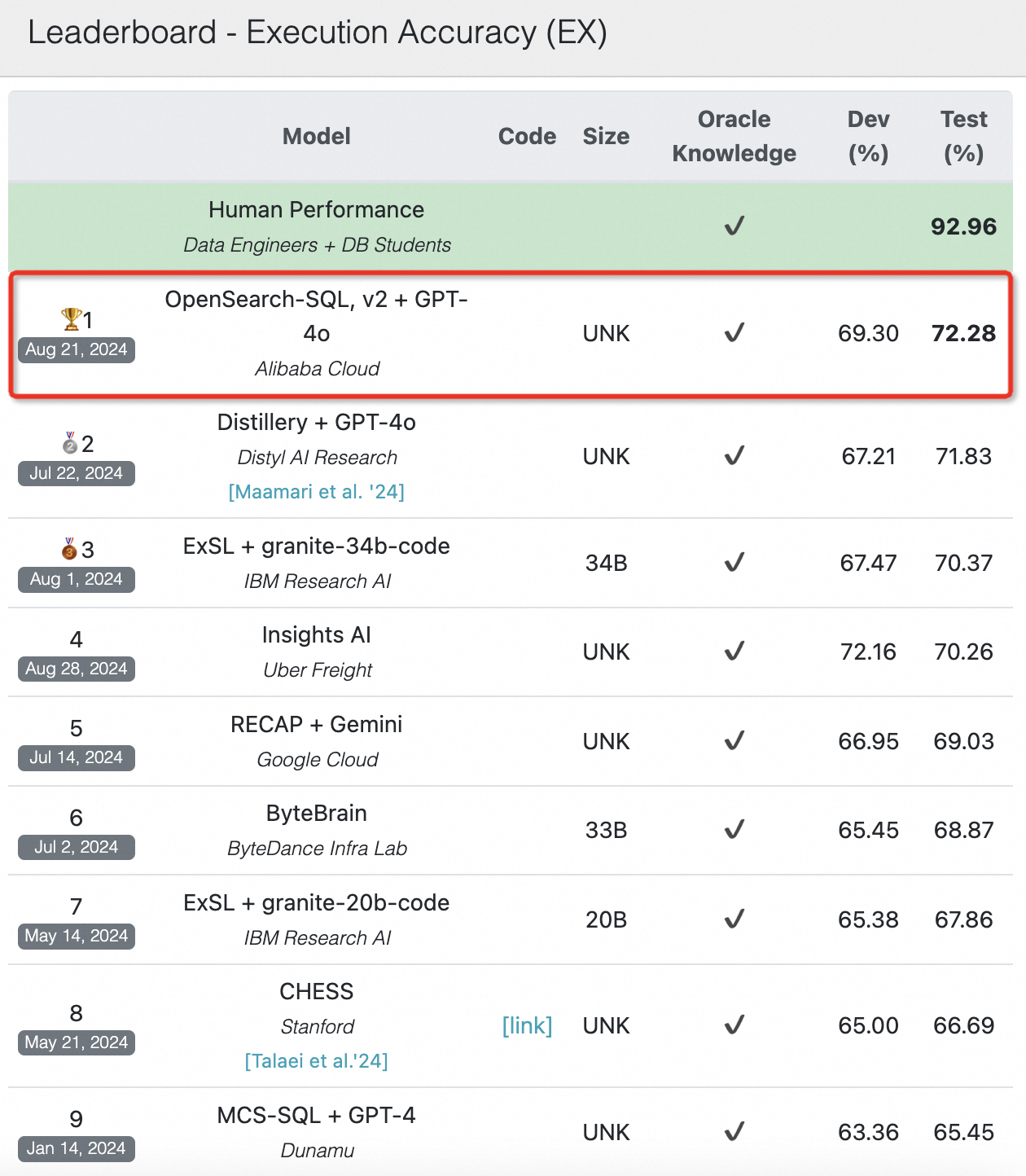

About benchmarks

Percentage results represent the number of operations completed within 1s, divided by the number of operations of the highest scoring case. Higher is better.

As you can see, the difference can be significant. The difference isn’t necessarily due to the strcmp cost as engines can sometimes use a string pool and compare by reference, but it’s also due to the fact that integers are usually passed by value in JS engines, whereas strings are always passed as pointers, and memory accesses are expensive (see section 5). In string-heavy code, this can have a huge impact.

For a real-world example, I was able to make this JSON5 javascript parser run 2x faster just by replacing string constants with numbers. Unfortunately it wasn’t merged, but that’s how open-source is.

2. Avoid different shapes

Javascript engines try to optimize code by assuming that objects have a specific shape, and that functions will receive objects of the same shape. This allows them to store the keys of the shape once for all objects of that shape, and the values in a separate flat array. To represent it in javascript:

const objects = [

{

name: 'Anthony',

age: 36,

},

{

name: 'Eckhart',

age: 42

},

]

const shape = [

{ name: 'name', type: 'string' },

{ name: 'age', type: 'integer' },

]

const objects = [

['Anthony', 36],

['Eckhart', 42],

]

A note on terminology

I have used the word “shape” for this concept, but be aware that you may also find “hidden class” or “map” used to describe it, depending on the engine.

For example, at runtime if the following function receives two objects with the shape { x: number, y: number }, the engine is going to speculate that future objects will have the same shape, and generate machine code optimized for that shape.

function add(a, b) {

return {

x: a.x + b.x,

y: a.y + b.y,

}

}

If one would instead pass an object not with the shape { x, y } but with the shape { y, x }, the engine would need to undo its speculation and the function would suddenly become considerably slower. I’m going to limit my explanation here because you should read the excellent post from mraleph if you want more details, but I’m going to highlight that V8 in particular has 3 modes, for accesses that are: monomorphic (1 shape), polymorphic (2-4 shapes), and megamorphic (5+ shapes). Let’s say you really want to stay monomorphic, because the slowdown is drastic:

// setup

let _ = 0

// 1. monomorphic

const o1 = { a: 1, b: _, c: _, d: _, e: _ }

const o2 = { a: 1, b: _, c: _, d: _, e: _ }

const o3 = { a: 1, b: _, c: _, d: _, e: _ }

const o4 = { a: 1, b: _, c: _, d: _, e: _ }

const o5 = { a: 1, b: _, c: _, d: _, e: _ } // all shapes are equal

// 2. polymorphic

const o1 = { a: 1, b: _, c: _, d: _, e: _ }

const o2 = { a: 1, b: _, c: _, d: _, e: _ }

const o3 = { a: 1, b: _, c: _, d: _, e: _ }

const o4 = { a: 1, b: _, c: _, d: _, e: _ }

const o5 = { b: _, a: 1, c: _, d: _, e: _ } // this shape is different

// 3. megamorphic

const o1 = { a: 1, b: _, c: _, d: _, e: _ }

const o2 = { b: _, a: 1, c: _, d: _, e: _ }

const o3 = { b: _, c: _, a: 1, d: _, e: _ }

const o4 = { b: _, c: _, d: _, a: 1, e: _ }

const o5 = { b: _, c: _, d: _, e: _, a: 1 } // all shapes are different

// test case

function add(a1, b1) {

return a1.a + a1.b + a1.c + a1.d + a1.e +

b1.a + b1.b + b1.c + b1.d + b1.e }

let result = 0

for (let i = 0; i < 1000000; i++) {

result += add(o1, o2)

result += add(o3, o4)

result += add(o4, o5)

}

What the eff should I do about this?

Easier said than done but: create all your objects with the exact same shape. Even something as trivial as writing your React component props in a different order can trigger this.

For example, here are simple cases I found in React’s codebase, but they already had a much higher impact case of the same problem a few years ago because they were initializing an object with an integer, then later storing a float. Yes, changing the type also changes the shape. Yes, there are integer and float types hidden behind number. Deal with it.

Number representation

Engines can usually encode integers as values. For example, V8 represents values in 32 bits, with integers as compact Smi (SMall Integer) values, but floats and large integers are passed as pointers just like strings and objects. JSC uses a 64 bit encoding, double tagging, to pass all numbers by value, as SpiderMonkey does, and the rest is passed as pointers.

3. Avoid array/object methods

I love functional programming as much as anyone else, but unless you’re working in Haskell/OCaml/Rust where functional code gets compiled to efficient machine code, functional will always be slower than imperative.

const result =

[1.5, 3.5, 5.0]

.map(n => Math.round(n))

.filter(n => n % 2 === 0)

.reduce((a, n) => a + n, 0)

The problem with those methods is that:

- They need to make a full copy of the array, and those copies later need to be freed by the garbage collector. We will explore more in details the issues of memory I/O in section 5.

- They loop N times for N operations, whereas a

forloop would allow looping once.

// setup:

const numbers = Array.from({ length: 10_000 }).map(() => Math.random())

// 1. functional

const result =

numbers

.map(n => Math.round(n * 10))

.filter(n => n % 2 === 0)

.reduce((a, n) => a + n, 0)

// 2. imperative

let result = 0

for (let i = 0; i < numbers.length; i++) {

let n = Math.round(numbers[i] * 10)

if (n % 2 !== 0) continue

result = result + n

}

Object methods such as Object.values(), Object.keys() and Object.entries() suffer from similar problems, as they also allocate more data, and memory accesses are the root of all performance issues. No really I swear, I’ll show you in section 5.

4. Avoid indirection

Another place to look for optimization gains is any source of indirection, of which I can see 3 main sources:

const point = { x: 10, y: 20 }

// 1.

// Proxy objects are harder to optimize because their get/set function might

// be running custom logic, so engines can't make their usual assumptions.

const proxy = new Proxy(point, { get: (t, k) => { return t[k] } })

// Some engines can make proxy costs disappear, but those optimizations are

// expensive to make and can break easily.

const x = proxy.x

// 2.

// Usually ignored, but accessing an object via `.` or `[]` is also an

// indirection. In easy cases, the engine may very well be able to optimize the

// cost away:

const x = point.x

// But each additional access multiplies the cost, and makes it harder for the

// engine to make assumptions about the state of `point`:

const x = this.state.circle.center.point.x

// 3.

// And finally, function calls can also have a cost. Engine are generally good

// at inlining these:

function getX(p) { return p.x }

const x = getX(p)

// But it's not guaranteed that they can. In particular if the function call

// isn't from a static function but comes from e.g. an argument:

function Component({ point, getX }) {

return getX(point)

}

The proxy benchmark is particularly brutal on V8 at the moment. Last time I checked, proxy objects were always falling back from the JIT to the interpreter, seeing from those results it might still be the case.

// 1. proxy access

const point = new Proxy({ x: 10, y: 20 }, { get: (t, k) => t[k] })

for (let _ = 0, i = 0; i < 100_000; i++) { _ += point.x }

// 2. direct access

const point = { x: 10, y: 20 }

const x = point.x

for (let _ = 0, i = 0; i < 100_000; i++) { _ += x }

I also wanted to showcase accessing a deeply nested object vs direct access, but engines are very good at optimizing away object accesses via escape analysis when there is a hot loop and a constant object. I inserted a bit of indirection to prevent it.

// 1. nested access

const a = { state: { center: { point: { x: 10, y: 20 } } } }

const b = { state: { center: { point: { x: 10, y: 20 } } } }

const get = (i) => i % 2 ? a : b

let result = 0

for (let i = 0; i < 100_000; i++) {

result = result + get(i).state.center.point.x }

// 2. direct access

const a = { x: 10, y: 20 }.x

const b = { x: 10, y: 20 }.x

const get = (i) => i % 2 ? a : b

let result = 0

for (let i = 0; i < 100_000; i++) {

result = result + get(i) }

5. Avoid cache misses

This point requires a bit of low-level knowledge, but has implications even in javascript, so I’ll explain. From the CPU point of view, retrieving memory from RAM is slow. To speed things up, it uses mainly two optimizations.

5.1 Prefetching

The first one is prefetching: it fetches more memory ahead of time, in the hope that it’s the memory you’ll be interested in. It always guesses that if you request one memory address, you’ll be interested in the memory region that comes right after that. So accessing data sequentially is the key. In the following example, we can observe the impact of accessing memory in random order.

// setup:

const K = 1024

const length = 1 * K * K

// Theses points are created one after the other, so they are allocated

// sequentially in memory.

const points = new Array(length)

for (let i = 0; i < points.length; i++) {

points[i] = { x: 42, y: 0 }

}

// This array contains the *same data* as above, but shuffled randomly.

const shuffledPoints = shuffle(points.slice())

// 1. sequential

let _ = 0

for (let i = 0; i < points.length; i++) { _ += points[i].x }

// 2. random

let _ = 0

for (let i = 0; i < shuffledPoints.length; i++) { _ += shuffledPoints[i].x }

What the eff should I do about this?

This aspect is probably the hardest to put in practice, because javascript doesn’t have a way of placing objects in memory, but you can use that knowledge to your advantage as in the example above, for example to operate on data before re-ordering or sorting it. You cannot assume that objects created sequentially will stay at the same location after some time because the garbage collector might move them around. There is one exception to that, and it’s arrays of numbers, preferably TypedArray instances:

// from this

const points = [{ x: 0, y: 5 }, { x: 0, y: 10 }]

// to this

const points = new Int64Array([0, 5, 0, 10])

For a more detailed example, see this link* .

*Note that it contains some optimizations that are now outdated, but it’s still accurate overall.

5.2 Caching in L1/2/3

The second optimization CPUs use is the L1/L2/L3 caches: those are like faster RAMs, but they are also more expensive, so they are much smaller. They contain RAM data, but act as an LRU cache. Data comes in while it’s “hot” (being worked on), and is written back to the main RAM when new working data needs the space. So the key here is use as little data as possible to keep your working dataset in the fast caches. In the following example, we can observe what are the effects of busting each of the successive caches.

// setup:

const KB = 1024

const MB = 1024 * KB

// These are approximate sizes to fit in those caches. If you don't get the

// same results on your machine, it might be because your sizes differ.

const L1 = 256 * KB

const L2 = 5 * MB

const L3 = 18 * MB

const RAM = 32 * MB

// We'll be accessing the same buffer for all test cases, but we'll

// only be accessing the first 0 to `L1` entries in the first case,

// 0 to `L2` in the second, etc.

const buffer = new Int8Array(RAM)

buffer.fill(42)

const random = (max) => Math.floor(Math.random() * max)

// 1. L1

let r = 0; for (let i = 0; i < 100000; i++) { r += buffer[random(L1)] }

// 2. L2

let r = 0; for (let i = 0; i < 100000; i++) { r += buffer[random(L2)] }

// 3. L3

let r = 0; for (let i = 0; i < 100000; i++) { r += buffer[random(L3)] }

// 4. RAM

let r = 0; for (let i = 0; i < 100000; i++) { r += buffer[random(RAM)] }

What the eff should I do about this?

Ruthlessly eliminate every single data or memory allocations that can be eliminated. The smaller your dataset is, the faster your program will run. Memory I/O is the bottleneck for 95% of programs. Another good strategy can be to split your work into chunks, and ensure you work on a small dataset at a time.

For more details on CPU and memory, see this link.

About immutable data structures

Immutability is great for clarity and correctness, but in the context of performance, updating an immutable data structure means making a copy of the container, and that’s more memory I/O that will flush your caches. You should avoid immutable data structures when possible.

About the { …spread } operator

It’s very convenient, but every time you use it you create a new object in memory. More memory I/O, slower caches!