An Introduction to American Law

本文是 https://www.coursera.org/programs/career-training-for-nevadans-k7yhc/learn/american-law 这门课的学习笔记。

文章目录

- An Introduction to American Law

- Instructors

- Week 04: Constitutional Law

- Key Constitutional Law Terms

- Supplemental Reading

- Constitutional Law: Part 1

- Constitutional Law: Part 2

- Constitutional Law: Part 3

- Constitutional Law: Part 4

- Constitutional Law Quiz

- 法律英语

- 后记

Instructors

Anita Allen, Henry R. Silverman Professor of Law and Professor of Philosophy, Penn Law, University of Pennsylvania

Shyam Balganesh, Professor of Law, Penn Law, University of Pennsylvania

Stephen Morse, Ferdinand Wakeman Hubbell Professor of Law; Professor of Psychology and Law in Psychiatry; Associate Director, Center for Neuroscience & Society, Penn Law, University of Pennsylvania

Theodore Ruger, Dean and Bernard G. Segal Professor of Law, Penn Law, University of Pennsylvania

Tess Wilkinson-Ryan, Assistant Professor of Law and Psychology, Penn Law, University of Pennsylvania

Tobias Barrington Wolff, Professor of Law, Penn Law, University of Pennsylvania

Week 04: Constitutional Law

The study of constitutional law is among the most exciting parts of the law because it provides for the structure and functioning of the U.S. government. In this module, Dean Ruger will address the document itself, how it has been applied over time, the history of the document, and what makes it unique. The structure of the U.S. government as a government of limited, separated powers will be explored along with the important individual rights the Constitution provides and how the U.S. Constitution compares to others around the world.

Key Constitutional Law Terms

Constitution

The most fundamental law of a country or state (http://www.law.cornell.edu/wex/constitution). The Constitution of the United States of America is the supreme law of the United States. Empowered with the sovereign authority of the people by the framers and the consent of the legislatures of the states, it is the source of all government powers, and also provides important limitations on the government that protect the fundamental rights of United States citizens. (http://www.whitehouse.gov/our-government/the-constitution)

Constitutional Law

The broad topic of constitutional law that deals with the interpretation and implementation of the United States Constitution.

Key Terms:

Articles of Confederation

The first constitution of the United States. For more information, explore this website: http://www.loc.gov/rr/program/bib/ourdocs/articles.html.

Bill of Rights

The first ten Amendments to the Constitution, which set out individual rights and liberties (http://www.law.cornell.edu/wex/bill_of_rights).

commerce power

Congress has the power to regulate the channels and instrumentalities of interstate commerce. Channels refers to the highways, waterways, and air traffic of the country. Instrumentalities refers to cars, trucks, ships, and airplanes. Congress also has power to regulate activities that have a substantial effect on interstate commerce http://www.law.cornell.edu/wex/commerce_power). The Commerce Clause refers to Article 1, Section 8, Clause 3 of the U.S. Constitution, which gives Congress the power “to regulate commerce with foreign nations, and among the several states, and with the Indian tribes.” For more, click here: http://www.law.cornell.edu/wex/Commerce_clause

Due Process

Phrase found in both the Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments, that no one shall “be deprived of life, liberty, or property without due process of law.” These words have as their central promise an assurance that all levels of American government must operate within the law and provide fair procedures. For more, click here: http://www.law.cornell.edu/wex/Due_Process

Equal Protection

The Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment of the U.S. Constitution prohibits states from denying any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws. In other words, the laws of a state must treat an individual in the same manner as others in similar conditions and circumstances. For more, click here: http://www.law.cornell.edu/wex/equal_protection

executive power

Article II of the Constitution outlines the duties of the Executive Branch, which is headed by the President. For more, click here: http://www.law.cornell.edu/wex/executive_power

Framers of the Constitution

Delegates hailing from all the original states except Rhode Island gathered in the Pennsylvania State House in 1787 to participate in the Constitutional Convention. Many of the delegates had fought in the American Revolution and about three-fourths had served in Congress. The average age was 42. (http://constitutioncenter.org/learn/educational-resources/founding-fathers/)

incorporation

Though the Bill of Rights originally only applied to the federal government, through this legal doctrine, portions of the Bill of Rights are applied to the states through the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. (http://www.law.cornell.edu/wex/incorporation_of_the_bill_of_rights)

judicial review

The idea that the actions of the executive and legislative branches of government are subject to review and possible invalidation by the judicial branch. Judicial review allows the Supreme Court to take an active role in ensuring that the other branches of government abide by the constitution. (http://www.law.cornell.edu/wex/judicial_review)

political party

Group of persons organized to acquire and exercise political power. Formal political parties originated in their modern form in Europe and the U.S. in the 19th century. Whereas mass-based parties appeal for support to the whole electorate, cadre parties aim at attracting only an active elite; most parties have features of both types. All parties develop a political program that defines their ideology and sets out the agenda they would pursue should they win elective office or gain power through extraparliamentary means. Most countries have single-party, two-party, or multiparty systems (see party system). In the U.S., party candidates are usually selected through primary elections at the state level. (http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/political party)

separation of powers

Political doctrine of constitutional law under which the three branches of government (executive, legislative, and judicial) are kept separate to prevent abuse of power. Also known as the system of checks and balances, each branch is given certain powers so as to check and balance the other branches. (http://www.law.cornell.edu/wex/separation_of_powers)

Taxing Power

Congress has power under Article I, Section 8 to lay and collect taxes, duties, imposts and excises, to pay the debts and provide for the common defense and general welfare. Under the 16th Amendment, Congress can collect taxes on incomes that are derived from any source. As long as Congress has the power to regulate a particular activity that it wishes to tax, it can use the tax as a regulating device rather than in order to raise revenue. (http://www.law.cornell.edu/wex/taxing_power)

Supplemental Reading

- The U.S. Constitution

- The Constitution from President Obama White House Archives

- “The Constitution of the United States: A History”

- “[Our Constitution](http://www.annenbergclassroom.org/Files/Documents/Books/Our Constitution/COMPLETED_Our Constitution.pdf)”

- Excerpt from Westlaw’s Black Letter Law Outline: Constitutional Law

Constitutional Law: Part 1

[MUSIC] Welcome to this segment of Introduction

to American Law, on the US Constitution. I’m standing here in the reading room

of Penn Law School’s library just a few miles from where the constitution

was framed over two centuries ago. In the city of Philadelphia. My name is Theodore Ruger. I’m a professor of constitutional law and health law at the University

of Pennsylvania Law School. And my segment today will focus

on various features of the US constitution’s distinctiveness. I’ll begin by asking

the fundamental question, what is the American Constitution and

American constitutional law. And focus specifically on the distinct

place of American Constitution and American constitutional

development in the world. Scholars and visitors to the US have long

recognized the US Constitution as unique. Going back almost 200 years, Alexis de Tocqueville,

on his visit to the United States, remarked specifically about America’s

unique constitutional culture. De Tocqueville observed, the obligation

to base decisions on the Constitution as opposed to the law was peculiar to the

American judge, at the time he visited. What he meant in this

is that many countries, of course,

had common law regimes and statutes. But, when De Tocqueville visited the US the US was unique in it’s

written Constitution.

Much later, in marking the Bicentennial

of the US Constitution in 1989, Time Magazine released a special issue in which it called our Constitution

a gift to all nations. And proclaimed proudly that 160 of

the 170 nations then in existence. That modeled their

constitution upon our own.

Around the same time,

Guido Calabresi leading scholar, dean of, former dean of Yale Law School and

a judge, described the other countries in the world

as our quote constitutional offspring.

I’ll explore these themes in this segment. And while it is true that

the US Constitution is distinctive. What we’ll see is that if,

if other countries are our constitutional offspring, as Judge Calabresi has said,

they’re an offspring that have take a very different path in some key ways

then the US constitutional development. In this segment I’ll explore

four different major themes. First, I want to talk about the basic

text of the Constitution and the long history of interpretation that

has taken place in American legal culture, which itself is virtually

unique in the world and forms a unique and distinctive aspect

of American constitutionalism. Then I’ll look at a few diff, different kind of broad clusters of

constitutional rights and structures. First, the manner in which our

constitution divides government and it divides it twice. Both vertically between the federal and state governments and then horizontally

across the federal government into the different branches of the legislature,

the executive branch and the judiciary. And I’ll explore some current

debates that resound even today about the proper allocation of

those different governmental structures. I’ll then turn to what many of us

think about when we think about the constitution, namely the individual

rights that we hold dear, and that government and

the courts struggle to mediate and strike the proper balance in, in applying

things like freedom of religion. The right to be free of

race discrimination. The right to bare arms,

the right to assemble as we choose. All of these form a core part of

the american constitutional tradition.

And although we don’t have time in this

segment to explore each one in great detail, I’ll explore some general themes

that I think cluster around the general area of independent individual rights

protection in the American tradition. Finally, I’ll conclude by talking about the US Constitution’s distinct

influence in the world. And the manner of which many other

countries that have recently adopted written constitutions somewhat along the

US model have chosen different paths and gone in different directions then,

then the US has in ways that I, then in turn shines a light on what’s truly

unique about the American experience.

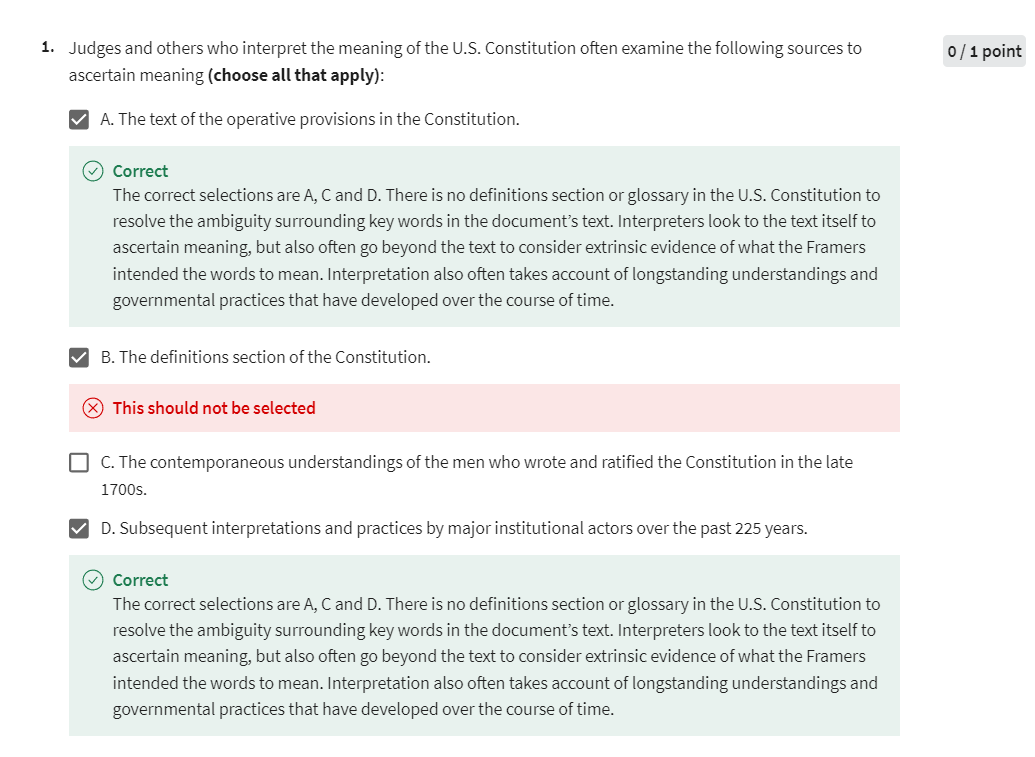

Now I’ll turn to the first

substantive section of this segment, which deals with the Constitution’s

basic text, history, and interpretation. Some general themes that

guide us as we think about the Constitution in specific

applications to individual rights areas.

The first most basic question

we might think about. And one, it’s one that people

have been struggling about for the entire life of the US Constitution,

is what is the US Constitution. Where is it? Where do we find it? Now, at first glance we might

think that’s a very simple answer. Of course, we have a written constitution. It has a text. And we might say, well,

that’s it and that’s all there is. As I’ll assert in the next few minutes, I

think that is dramatically wrong, both in, as a descriptive matter of the way

the Constitution has been interpreted and as a normative matter of how

we ought to interpret it.

But, let’s talk about the text and

the history a bit to start out with. I hold in my hand here the full text of

the constitution in this little booklet. It’s a booklet I picked up at

the Supreme Court many years ago. The Constitution of

the United States of America. As you’ll see this is a slim document and

as I’ll, I’ll describe in, in detail in a few minutes,

this is the world’s shortest constitution. And the, the brevity of our constitution

itself is it self important, and it creates a kind of

interpretative imperative. These words in this little

document are often vague and unspecified, and

they don’t interpret themselves. And much of what the american

constitution tradition has been over the past many centuries,

has been an effort to translate and give content to these very sparse and

undefined words.

So we might say,

where is the Constitution? Is it in the text? I would say, yes it is. But it’s not fully embodied

in this tiny little, little booklet that I hold in my hand. Where else might we look then? We do need to think about the text and

the text is one thing that endures. But as we look at the his,

history of constitutional development in the United States,

we see the, the role of time. And here I mean the several centuries that

this constitutional text has been with us, is important, and is foundation in

how we think about the document. The document stays with us, but

our we as a people change over time. And that inflects and

affects the way we interpret the document. And we can see real life

examples in the Supreme Court of the way the court itself changes in

its own interaction with the document.

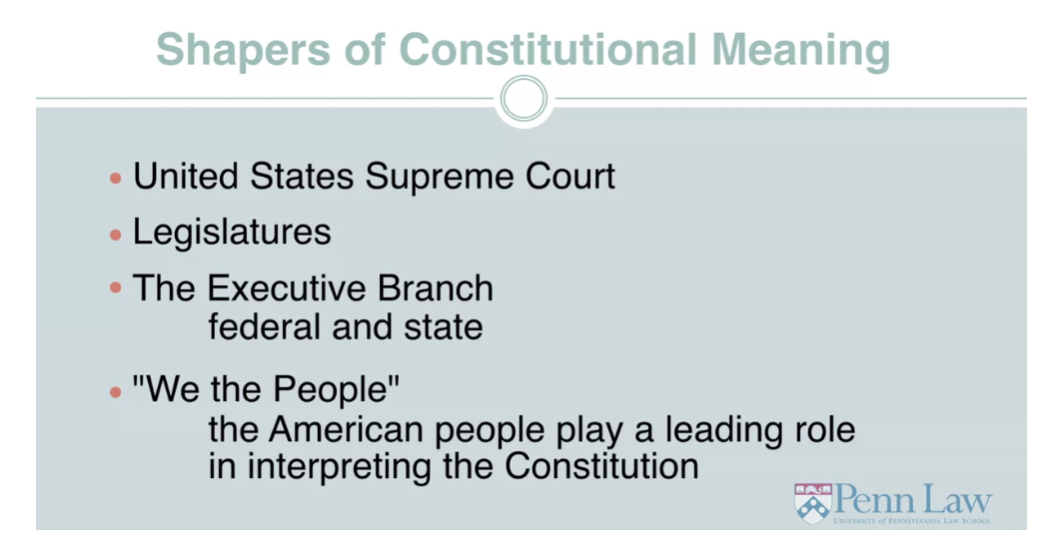

We also have a crucial role in,

in American history in the institutions that shape and

contest constitutional meaning. When we talk about those institutions, obviously the primary institution we talk

about is the United States Supreme Court, a group of, these days, nine unelected

judges who sit in Washington DC. Originally for much of the nation’s

history the court had fewer than nine. Justices but we, we,

when we talk about constitutional meaning we need to look beyond the court and think

about all of the other institutions in our civic society that that

participate in interpretation.

Legislatures, indeed in the early

days it was primarily legislatures. and, non judicial actors that participated

in constitutional interpretation. The executive branch, certainly at the

federal level as well as the state level is a focal point where the vast majority

of decisions about constitutional rules are made much more so than the very few

cases that reach into the supreme court. And then much more broadly, and in ways

that constitutional scholarship has started to take account of

within the last decade or two, these words at the bottom come

right from the constitution itself, We the People, the American people

in all of our kind of diverse and often contested debates over

constitutional meaning. We play a leading role in

interpreting the Constitution and in updating its meaning through the

generations over the past two centuries.

Let me say a bit more about the text and

history by returning to where these all started just

a few miles from where I stand here today. In the old city of Philadelphia here in

this building called Independence Hall. It’s important to note, and

then very important for the American constitutional story

that the framers of this country, and of the Constitution, met here twice,

separated by more than a decade. They met in 1776 while still part of the British Empire to frame

a document that’s central to our. Political tradition called

the Declaration of Independence, declaring that this nation would,

would, would form free of Britain and and

chart a course as a new nation. And we celebrate that day, July 4th, 1776. One day we don’t celebrate is July 12th, 1776

Because after the Declaration of

Independence, which we all remember, the framers sat around, and they drafted

a constitution for this new nation. It’s call, it was called

the Articles of Confederation. And it was, that was draft was issued and initially approved by an initial

vote on July 12th, 1776. Now today,

that is not a date we celebrate in United States history because

the original constitution. Was, in many senses a failure. And so the framers had to come back

again in 1787 to essentially do version 2.0 of the constitution. And this is important for the way we

think about the constitution, because we, our constitution that endures with

us today then, was born out of a failed experiment in constitutionalism

called the Articles of Confederation. What was wrong with the articles? They created a government

that was too weak. There was no central executive,

there was insufficient power to tax and on, at the national level there

was insufficient ability to reign in the self interested and

counter productive behaviors of state governments that would do things

like enact their own internal tariffs. Engage in their own foreign policy. and, and things of that sort. Simply put the articles of confederation

was no way to run a serious nation state.

And when the so the framers when they

gathered in 1787 were trying to do two. Things which are, were in tension then and

remain in tension and create some of our greatest

constitutional debates. They were trying to structure

a government that was restrained and protected individual liberty. And the, these,

those values remain important and central to,

to our constitutional tradition. But at the same time, keeping in mind the failures of

the Articles of the Confederation. They were trying to create a government

that worked, and that had the strength and efficiency and capability to address

national problems on a national scope.

The important compromise of the Constitution is that it balances a limited government, that protects individual liberty, with a government that is strong enough to address national problems. The Articles of Confederation failed in great part because it lacked this second element.

So, it’s these conflicting impulses

that we see today, even in debates say, over the new Affordable Care Act

passed a few years ago. Which attempts to address national

problems of health care on a national scale. And which has generated constitutional

debate over individual liberties. Even as it tries to address

pressing health problems. These debates don’t go away. They are essential to our

constitutional culture. And they, in a sense, date all the way

back to these beginning principles where the Framers tried to do,

to do two very different things. The most important Founding Father, James Madison, was aware of this internal

tension and expressed in, in writings. In important writings called

The Federalist Papers. So Madison said in Federalist fifty one. Quote in framing a government which is

to be administered by men over men, the great difficulty lies in this. You must first enable the government

to control the government, and in the next place,

oblige it to control itself.

Consider Madison’s words in

the context of our present, present debates today which

bear the same internal tension. First, we want a government that

is strong enough robust enough to control the governed, governed and, and effectuate legitimate solutions to

the problems we face as a nation. But we also want a governmental structure

and we want a constitution that controls the government itself and

protects individual liberty, and structures governmental

decision making in a way that. Promotes the optimal

functioning of our democracy. These are the things that the men who met

here over two centuries ago struggled with and attempted to strike a balance with. And it’s the very same balance that

in our own constitutional debates and interpretation we attempt to strike today.

Let me now turn to some specific

choices the framers made in 1787 about the document itself that still have

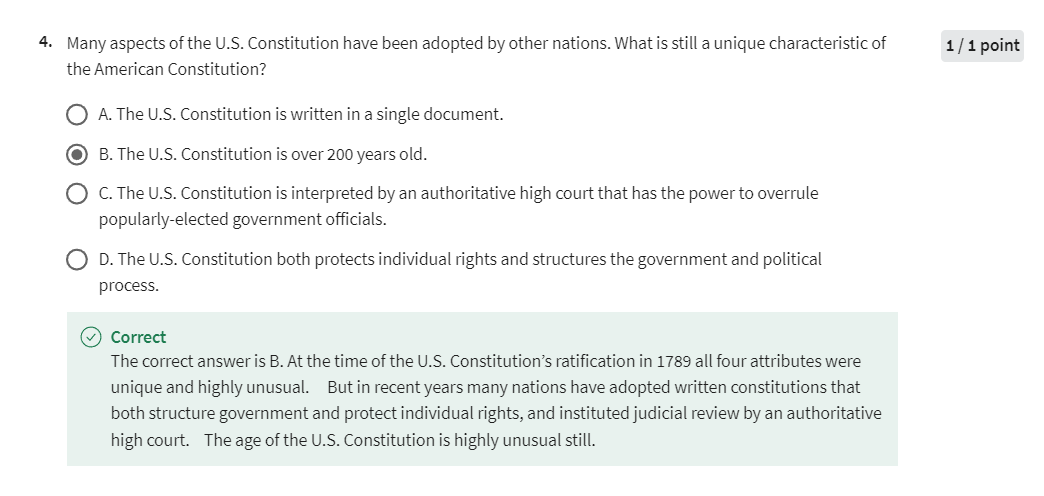

major interpretation implications for the way we think about the constitution. So what is unique about the actual

text of the constitution? The first thing that’s unique, and that we take for granted a bit, most

countries in the world have now, finally. Followed our lead on but was very unique in 1787 was the very

fact of a written constitution. Lots of countries including perhaps

most notably Great Britain, have long constitutional traditions. But until very recently those traditions

and the constitutional culture and rules of those societies. Were not captured and collected and

written in a single short document. Another unique feature about

the US Constitution is not just that it was written but how few words

the framers used in their writing of it. The Constitution comes in

at just over 4,000 words, which is remarkably short by comparison

to other constitutions in the world. Compared to the longest constitutions

we see both around the world and in our own state governments. The US Constitution is remarkably short,

again, at just over 4,000 words. By comparison, the Constitution of the

nation of India in it’s English language version is almost 120,000 words long and even that isn’t the longest constitution

that we have in this library. That would be the Constitution

of our own state of Alabama. Which clocks in at over 300,000 words. By this standard of course, then to use a few thousand words as

the framers of the US Constitution did to set up an entire government

structure is incredibly sparse. And that very brevity,

I has clear interpretive interpretations. With so few words there was no time for

definitions clauses, or lengthy explanations of the key

constitutional provisions. Instead our core constitutional

guarantees, and our core structural provisions that structure

government, are laid out in clear, but very sparse terms, which indeed I would

invite subsequent generations to. Interpret and, and

put substance in to those sparse phrases. This is something I’ll talk

more about in this segment.

Not only is the US Constitution

extremely short, it’s also extremely difficult to change. It is among the World’s Constitutions,

the hardest to amend the text. The provisions for

amendment are set forth in a very short provision of the Constitution called

Article V and the most important point is they require extreme super majority

approval by the US states. By super majority I

mean far more than 50%. Indeed three quarters of

the individual states. Need to consent in order for any amendment to be made to

the text of the Constitution. What this means is the text is

extremely difficult to change. The difficulty in amending

the Constitution carries with it extreme interpretive implications. Because the text is so hard to change in

order to update constitutional meaning. With a text that is largely set in stone. The interpreters of the Constitution

led by the Supreme Court, occasionally must revise or update their

understandings of constitutional meaning. This is something we see over time, over

the generations at the Supreme Court, and it’s a central part of out

constitutional culture, that the text itself stays the same. While the legal interpretation

of that text changes over time.

Relatedly the US constitution is

the oldest continuously operating constitution in the world. As I alluded to before and

will return to at the end of this segment. Written constitutionalism backed

back a strong supreme court, is becoming the world’s norm. But for most countries it’s

a phenomenon that has happened only in the past century. The US with a constitutional tradition

stretching back over two centuries has a much longer process of institutional

development than other countries, which itself is a key feature of

our constitutional culture and it affects interpretation

even to the present day. All of these variables that

I’ve been talking about. The writtenness of the Constitution, its

extreme brevity, its age, the difficulty in changing the Constitution, combine with

yet another feature about any kind of written language, which is

the inherent ambiguity of language. And this is a short a Constitution,

in the United States, which contains. Some phrases which are very vague and

don’t come with definitions clauses, and I’ll show you some examples. Some parts of the Constitution are written

in language that is crystal clear, even today. And generally, most readers of the English

language would agree in what it means. Many other parts of the Constitution,

including some of the very most important Parts, are written in language

that was extremely vague then and remains Extremely vague and

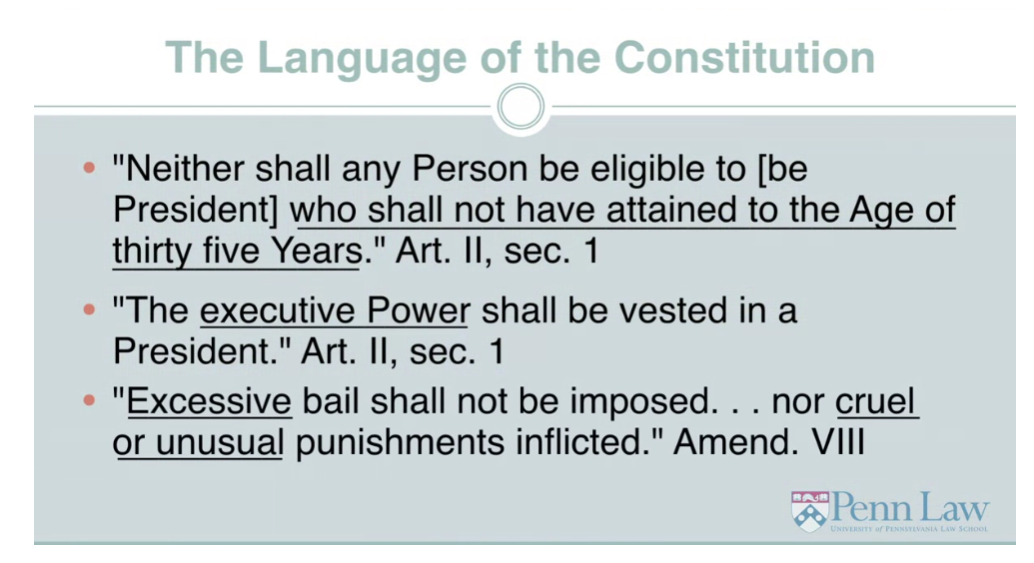

compels subsequent interpretation. So for instance the Constitution contains

a very clear requirement about the age of the President. It says, no person shall be

eligible to be President who shall not have attained

the age of 35 years. That’s clear,

it was clear when it was written. And it would be clear today where

any controversy over that to occur. But consider another phrase also

from article two which says, the executive Power should

be vested in President. This is one of the most crucial

foundations of the modern bureaucratic state. This power, the executive power,

on which our entire administration is founded with almost a million employees

virtually everything, everything we think of as the federal executive branch

its authority rests on this clause. Yet the basic phrase here,

the key operative phrase, executive power, is not defined

anywhere in the Constitution. In order to give meaning to that,

what judges and other participants in constitutional debates have had to do over

the past 200 years is contest, debate, and fill in their own interpretation

of what executive power means.

Likewise in the key provisions that

protect our individual rights, some of the most important phrases

are inherently vague and ambiguous. The eighth amendment

prohibits excessive bail. What does excessive mean? It prohibits cruel and

unusual punishments.

What’s cruel to one person may

not be cruel to somebody else. These are clauses that come

without definitions and without explicit user instructions,

and this is important and this was intentional by James Madison and

the other framers. They did not want a document that

would be fixed in time with explicit. User code, instead,

they envisioned a document where each generation would supply its own

definitions for these grand, but yet inherently vague provisions

in the Constitution.

So, how has, how have subsequent interpreters

given meaning to these clauses? And here I bring in a concept

I mentioned a few minutes ago. Namely the notion of institutions and institutional development in

the American Constitutional traditional. We have in our constitutional order

a predominant institution for, for giving meaning to the Constitution. it, we, it’s called the US Supreme Court. And although it wasn’t perhaps

envisioned as such by the framers, very early on in America’s constitutional

development the Supreme Court became the leader institution that gave meaning

to the vague phrases of the constitution. Historically I want to mention

Chief Justice John Marshall. The first great chief justice

of the US Supreme Court, who served for

the better part of the early 19th century. Marshall and his colleagues on Supreme

Court in this era where the ones who began giving the Supreme Court

the prestige that it enjoys today as the leading interpreter

of the Constitution in the US. And Marshall had a very specific vision

for interpreting the constitution. He said in the leading early case

of McCulloch versus Maryland. We must never forget it is

a Constitution we are expounding.

Now what does that mean? He was distinguishing constitutional

interpretation from the interpretation of many other sorts of legal documents. Ordinary consumer contract

ordinary statutes and regulations, wills and

trusts, the ordinary stuff. Of law that judges and

other people deal with on a daily basis. The Constitution in Marshall’s

vision was something different, and it was something that was

intended to endure for much longer. Recall what I said about the extreme

brevity of the Constitution. And the fact that it doesn’t

come with definitions clauses. For Marshall, as for many people who have

followed him, what this means is that judge and other interpreters of

The Constitution over time need to supply their own interpretive effort and

interpretive analysis to these clauses.

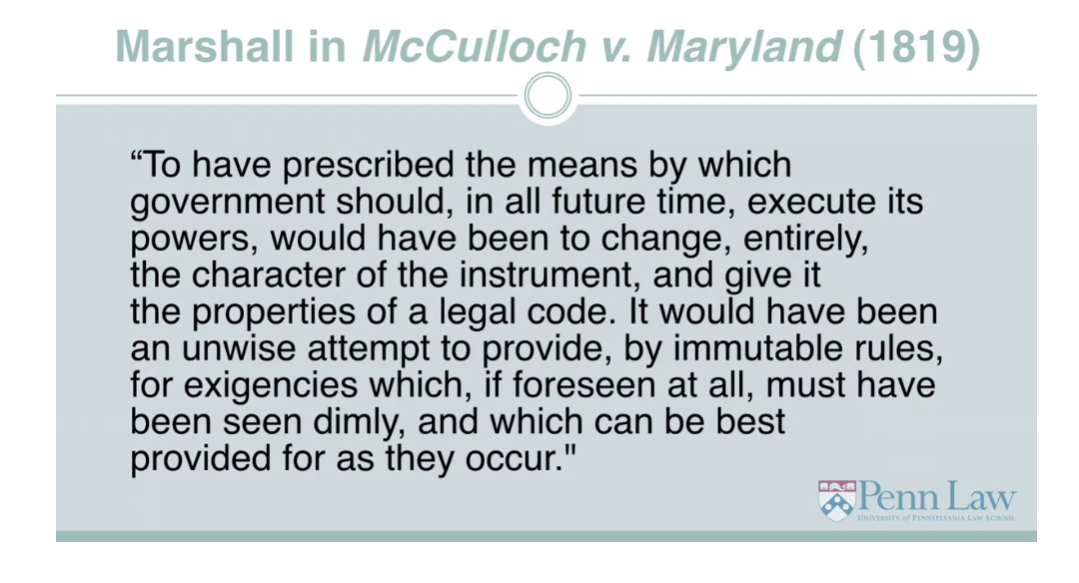

Moreover although The Constitutions text remains fixed it’s

interpretation does not. And here we see Marshall arguing

that it would be unwise to provide immutable rules which would lock

constitutional meaning in place. Instead Marshall and

many who have followed him argue for more evolving constitutional culture.

So given the necessity of

subsequent interpretation in our constitutional tradition,

who does the interpreting? Which institutions, which people? The central point is that interpretation

is diffused, pluralistic, and multi-faceted in the US

constitutional tradition. Yes, the Supreme Court has come to be the

leading constitutional interpreter, but by no means is it the only key institution

infusing the constitution with meaning. In the earliest days of the american

republic, the supreme court was largely on the sidelines, instead,

the most heated debates took place in the halls of congress,

in the chambers of state legislatures, and in the public square itself,

the public and the media of the 19th century being explicitly and intently

involved in constitutional interpretation.

So to today, although the US supreme court

has ascended to a predominant place in American constitutional interpretation, by

no means is it the exclusive interpreter. And on some issues, it is not the most important

interpreter of constitutional meaning. What has happened over the past 200

years through the rise of what we call strong form judicial review,

is that the court has attained a pre, predominance in constitutional

interpretation to agree, to a degree that the framers

probably didn’t foresee. And this started to happen early on and indeed John Marshall, once again,

was a key architect of this strategy.

In a famous case in 1803 called

Marbury versus Madison Marshall for the first time asserted the proposition

that it was the Supreme Court. Who was tasked with giving

meaning to the Constitution. Marshall said it is,

it is emphatically the province and the duty of the judicial

department to say what the law is.

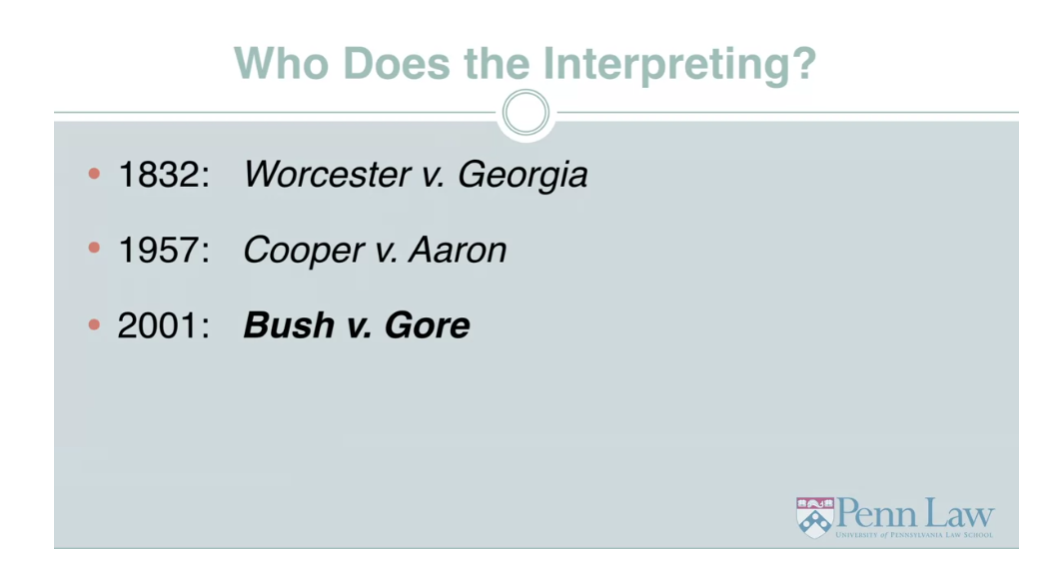

I’ve spoken about the institutions that

give the Constitution meaning to return to one last point that I

alluded to minutes ago. Let me speak about the role

of two centuries of time and historical development in creating

the constitutional culture we have today. Here I would focus on three

separate Supreme Court cases, separated by almost two centuries. The first of these was the case

of Worcester versus Georgia. This case, arising in 1832. Involved a review of the state

of Georgia’s forced expulsion of the Cherokee Indian tribe. Georgia had enacted

policies in taking steps to oust most Cherokees from

the borders of their state. And this was in violation

the Supreme Court held of various laws and treaties of the United States. Georgia was acting unlawfully in

doing this vis-a-vis the Cherokees. What happened in the aftermath of that

decision was telling about the weakness of the Supreme Court in this prior century. As history tells us

President Andrew Jackson allegedly said, John Marshall has made his decision,

now let him go enforce it. And, of course the justices of the court

had no means of enforcing this. And what happened is the sad story that

the Cherokee tribe was indeed ousted from Georgia despite the fact that they had

won a legal victory in the Supreme Court. It was an empty victory because the other

institutions in American life, which would have had power to enforce that decision

against Georgia stood on the sidelines and let Georgia unlawfully oust

the tribe from its borders.

In the time of Worcester v. Georgia, the American system of checks and balances wasn’t fully functional, because the judiciary relies on the executive and other institutions to enforce its mandates; it cannot enforce anything on its own.

Very different story with the passage

of a hundred years later. And another contested decision also

involving another southern state. Cooper versus Aaron involved efforts

to integrate the little rock Arkansas schools. Just a few years after the landmark

Brown versus Board of Education decision in 1954. The law of the land as articulated by

Brown and subsequent supreme court cases was that,

segregated schools were illegal. And that the African American students

who wished to attend high school in Little Rock, had an airtight

constitutional right to do so. But again, the opinions that the supreme

court issues are merely words on a piece of paper. As we saw in the Cherokee Indian case

with Georgia without enforcement from other parts of society, those words

would be idle victories indeed. What happened after Cooper versus Aaron though, tellingly, was President Dwight Eisenhower

mobilized the 101st Airborne, sent troops down,

sent federal troops down to Little Rock. Who stood guard over the Little

Rock High School and ensured that the African American students who had won

their legal victory had that translated into the actual victory of being able

to attend school in Little Rock. So the Supreme Court’s legal ruling was

accompanied by immediate acceptance and enforcement by other

branches of government. And we saw this even much more

recently in the hotly contested Bush versus Gore decision involving

the 2000 presidential election. Both sides claimed

victory in the election. Both sides claimed to have

the law on their side. But the minute that Vice President Al Gore

had been declared to have lost the election by the Supreme Court in

a very controversial decision within a day of that decision, Vice President Gore

was on TV conceding the election and, and allowing a peaceful transition

of power to President George W Bush. Something that would not happen in

certain other countries even today and would not have probably happened in

the United States in the earliest days of the Republic.

The point being we’ve had the text for

over 200 years of our constitution. We’ve had the Supreme Court for

over 200 years, but this nuanced and sophisticated acceptance

of the role of the Supreme Court. And the enforcements of its decisions in

our constitutional culture is something that it took quite a bit longer to attain. And this is a lesson and an instructive

one I think for those who say that US constitutionalism is being exported

around the world to other countries. It is true that that is being done, but to truly export,

the US constitutional structure. We need to do much more

than export the text. Instead, we need to export the text and

the institutions, and in some cases, perhaps wait for the passage of time in other nations that

don’t have a constitutional tradition in order to have the kind of

framework that we have here. [MUSIC]

Constitutional Law: Part 2

[MUSIC] Let me turn next to the next

part of this segment. Which deals with the structural

provisions of the constitution. How the government is set up and

structured. When the framers met here

in Philadelphia in 1787, they were primarily concerned with

this part of constitutional ordering. Bear in mind, they had just split away

from a government which they thought was terribly structured, giving far too much

power to the whims of a given monarch. And in setting up the new

American constitution, in light of the failures of the Articles

of Confederation, it was important for the framers to get it right and

give the right kinds of power and the right amounts of power to

different parts of government.

Here we turn once again to

the views of James Madison, and the most important of the framers who was

a student of governmental structure and proper allocation of authority,

and thought quite a great deal and wrote a great deal about the best

way to structure government. And he acknowledged a basic challenge

which I’ve alluded to before. First the framers sought to give

the government enough power to control the governed, but then structure it in

such a way as to use Madison’s phrase, oblige it to control itself. For Madison the solution to this dilemma, sought in, actually, lay in the basic

ambition of the men and, today, men and

women who occupy spots in our government. Recognizing, then, as now,

that the inherent ambition of people, who would seek places in government. Madison and the other framers sought to

build a government where this ambition was a built in feature. And one that would perhaps solve the

problem of too much ambition in one place.

So as Madison said, ambition must

be made to counteract ambition. The interest of man must be connected

with the the constitutional rights of the place.

For Madison this meant

that the best solution for structuring government was dividing

power and creating incentives for one branch of government

to counteract the other. We call this separation of powers or

checks and balances. And the framers cared so much about this that they didn’t

just do it on one dimension. But they did it on two dimensions. And here what we mean is when we

talk about separation of powers in the federal government we often use the

phrase horizontal separation of powers. Splitting the government into three

branches, executive, legislative and judicial, and

giving each one of them certain powers and more importantly propose this theory of

behavior that Madison advances giving each branch the incentives to counteract and be somewhat jealous of

the other branch’s power. But, the framers didn’t

just divide constitutional, our constitutional order that way,

they also did it on, what we would call, a vertical dimension, namely, dividing

power between the National Government and the various state governments. This is a principle we call federalism and

it is very important even today, as certain things are certain

important policy choices are situated with the states, even as

many important policy objectives have come to be viewed as national

government prerogatives. And it’s on these two dimensions, the horizontal separation of powers

within the federal government and the vertical separation of powers between

the states and the federal government. Where our greatest debates over

governmental structure continue to reverberate in the Supreme Court and

in the broader public policy debates.

James Madison’s fundamental

insight that power was more safely reposed in government. When it was broken up into smaller chunks

and given to different branches or even different governments

as between the national and the state government is one that

remains important today even as we debate the precise boundaries

of those divisions. For the modern Supreme Court it

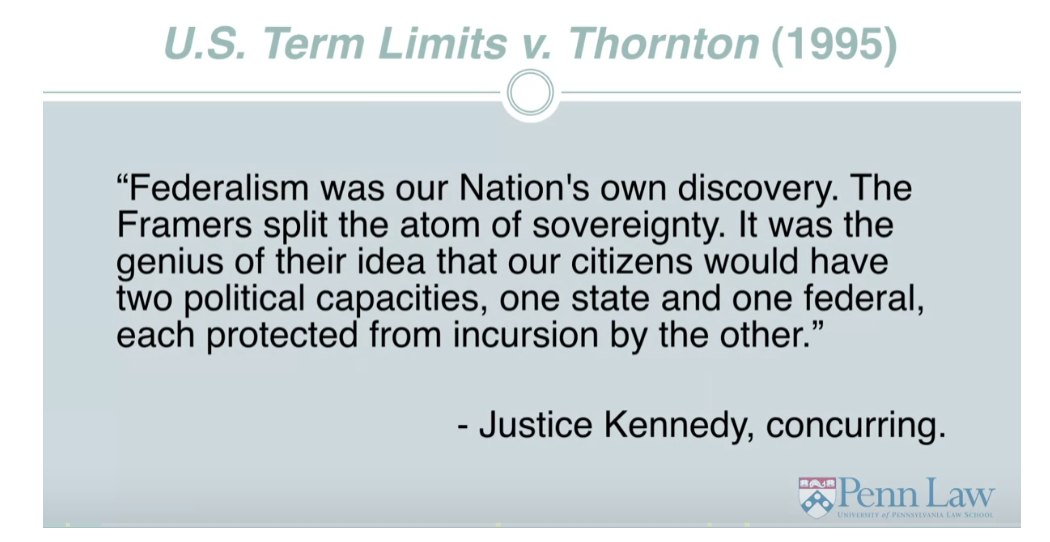

has been important particularly in the last few decades. Justice Kennedy in a representative

statement in a case called U.S. Term Limits versus Thornton called

Federalism Our Nations’s Own Discovery. And he talked about the framers splitting

the atom of sovereignty as a genius idea. Giving our citizens two political

capacities, one state and one federal, each protected

from incursion by the other.

Now Justice Kennedy’s statement may

be a somewhat idealized version of our federal order. In reality, many,

perhaps most public policy issues are, are shared between the state and federal

governments, who cooperate or conflict or wrangle over the proper

sphere of authority. But still, for many citizens and

many judges, and many policy makers. This question of where we allocate

authority in our constitutional system remains crucially important and as hotly debated today as it was

over 200 years ago in Philadelphia.

Now the way that the Supreme Court and

others have operationalized these broad general principles about sep,

separation of powers. Is through the development of specific

doctrines in particular cases. Recall what I said earlier that

the basic framework parts of the constitution don’t come with

definition clauses or users guides. It has been the task of subsequent

generations over the past 200 years to give content to these broad general

principles, like executive power, legislative power, judicial power, or the

broad principles that there ought to be some separation between the states and

the national government. And the way the Supreme Court has done so

is, over the past 200 years, to very gradually,

very incrementally craft different doctrines that go to both separation

of powers on the horizontal level and the vertical level, the so

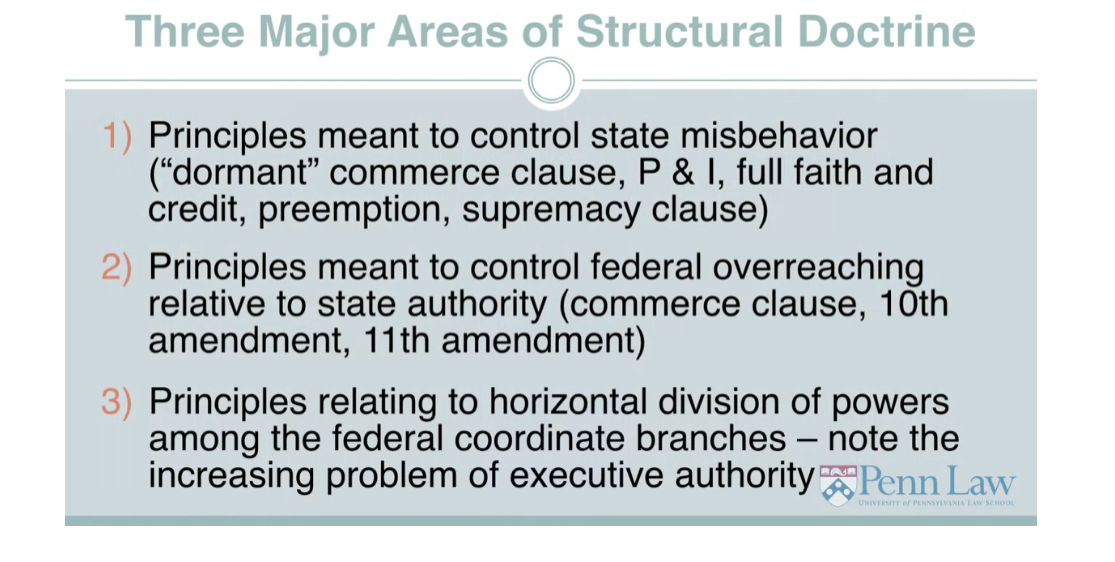

called federalism doctrines. It’s useful to divided this

general concept of separation of powers into three basic areas

of doctrine and analysis.

The first of two of which deal with

relationships between the state and the federal government. The third deals with the, what we call the horizontal relationship

across the federal government. So first the Supreme Court has applied the

Constitution over the past two centuries in ways to control the states and

limit state behavior, or even misbehavior. Second, and increasingly in recent

decades, the Supreme Court has applied Federalism doctrines to restrain the

Federal Government as against the States, to say that there are some spheres where

the Federal Government can’t legislate, no matter how powerful it may claim to be. And finally,

there’s another set of doctrines that are continuously under development and

debate that attempt to create limits between the different

branches of the federal government. And occasionally the Supreme Court will

address cases that asks the question, is the president

exercising too much power. Has Congress overstepped its bound in,

in this case? I’ll speak to all of these

doctrines in the next few minutes.

But I want to highlight yet another debate

in this area, which is the question of who should decide these major

separation of powers questions. To be sure, the Supreme Court has

asserted that it has the right to decide these fundamental questions

of governmental structure just as it does other questions of law and other

questions of individual rights protection. But there is a long scholarly tradition

rooted in constitutional history that suggest that these basic structural

choices about the constitution ought to be what we call non justiciable. In other words, decided outside

the courts by the major political branches of American government. After all, remember James Madison’s

phrase ambition must be made to counteract ambition. For Madison at least, the government

is already properly structured, so that if the President overreaches,

Congress ought to step in and reign in Presidential power. Conversely, if Congress is

exceeding its authority, perhaps the President will

refuse to enforce that statute. And there’s a real question about

whether the Supreme Court needs to referee all these disputes. On the other hand,

developments that Madison and his colleagues never could have foreseen

have complicated the separations of powers mix on all of these dimensions,

and perhaps given rise for stronger arguments for

judicial supervision. For instance, the framers for

all of their wisdom, never anticipated modern political

parties and the modern two party state.

And the implications that the two,

two party system would have for separation of powers. When the same party controls both Congress

and the White House the assumption that ambition will counteract ambition, and

Congress will reign in the President, falls apart in a world of

strong party discipline. Likewise, the framers never foresaw

the dramatic rise and the size and scope of the federal Executive branch that

has taken place over the past century. In the early days of the Republic, the federal government had only a few

thousand, non-military employees. Today the federal government has

over a million such employees. Growth of the federal government over

that phase has, some would argue fundamentally tipped the power of the

presidency relative to the other branches. These are questions that

are still debated, and that I’ll return to in a few minutes.

Now let me go somewhat more systematically

through these different areas of doctrine. The first area where federalism doctrines

have been applied by the supreme court and are baked into the constitution deal

with controlling state behavior or even state misbehavior. Indeed, were we to travel

back in time to 1787 and asked the framers what

they worried most about. They would not have worried about

an overreaching federal government. After all, recall how weak the federal

government was under the Articles of the Confederation. What they worried about, and the reason

they came back to Philadelphia in 1789, was that states were behaving badly. States were printing their own money

to let their own debtors off the hook. They were couldn’t agree

on state boundaries. They couldn’t agree on foreign policy, or policy toward the Native American tribes. Each state was going in its own direction. States were enacting internal tariffs and trade barriers, of the sort that

today we see between nation states. But this used to happen between

Pennsylvania and New Jersey. The Framers regarded this as no

way to run a proper country. And so one of the first things

the constitution did was prohibit and provide doctrinal grounds for courts to prohibit states from engaging

in this kind of individualistic behavior.

A later justice,

an important justice from mid 20th century Justice Robert Jackson said that

these clauses taken together were to declare something he called

a Federal Free Trade Zone. So if you imagine efforts such as our

undergoing these days in Europe to create a, to transform what used to be

individual markets into a national free trade zone, that was a major impulse of

the early days of the Constitution, and largely successfully enforced by the

Supreme Court over the last two centuries. Such that these debates occur,

but occur much more, much less frequently than they would

have in the early days of the Republic.

Dormant Commerce Clause:

The Commerce Clause of the Constitution gives Congress the power “to regulate commerce among foreign nations and among the several states.” The Supreme Court holds that there is also implied a “dormant commerce clause” that prohibits individual states from regulating commerce affecting other states. Only Congress has this power.

Modern debates over the scope of federal

government authority often grapple with the fundamental tension and inconsistency

that’s built into the Constitution. On the one hand the baseline rule in the Constitution is

that power resides with the states and the people, and the national government

only has those powers that the document. And interpretations of

the document affirmatively give to the national government. This is called the doctrine

of enumerated powers. And it is often invoked by people who

say that the federal government is over-reaching its authority, because it

can’t point to a certain enumerated power. On the other hand, some of the enumerated

powers themselves are extremely broad and extremely vague. The most important of these is the

Commerce Clause which gives the national government the authority to regulate

commerce among the several states. And today the Commerce Clause

stands as the foundation of much national government authority. Now the meaning of this clause typically

is not defined in the Constitution, and has been contested heatedly over the past

two centuries, indeed over the past few decades, in the context of major statutory

enactments like the Affordable Care Act. It’s possible to think about the Commerce

clause and the history of its development in four main historical epochs, and

I’ll summarize these briefly here.

First, for much of the first hundred

years of the constitution’s life, until about the 1870s or

1880s Commerce Clause cases were few and far between, precisely because the

National Government didn’t do that much. In a series of decisions, in this period,

that might surprise modern observers. The Supreme Court took a very narrow and formalistic definition of the Commerce

Clause, and, issued decisions saying things like manufacturing in a major

sugar plant was not commerce and therefore that company was not

subject to basic anti trust laws. Or even more strikingly

a factory that employed chird, child workers was not engaged in commerce. Therefore the National

government had no basic, no authority to issue basic

child labor legislation.

This was a constitutional regime,

which seems anachronistic to us, and indeed it proved unsustainable,

even in a much earlier date, namely in the New Deal in the 1930s and

the 1940s. After the Supreme Court struck down some

of President Franklin Roosevelt’s most popular and important recovery

initiatives President Roosevelt capitalizing on public dissatisfaction

with a court that seemed to be stuck in the past proposed what

would have been a radical solution, namely adding more justices to the Supreme

Court in order to reverse those rulings.

Perhaps sensing the public

outcry against its decisions and wanting to avoid the constitutionally

problematic strong arming from President Roosevelt,

the Supreme Court, by the middle of the New Deal reversed its prior narrow

interpretation of the commerce clause and adopted something much more familiar to

the doctrine we have today from the court. Namely, that commerce is defined pretty

broadly to include any activity that affects the national economy,

however small, so long as if taken in its totality in an

aggregate sense it has an economic impact.

So this is the law today and

indeed the law from, from about The New Deal Era, up until the

time I was in law school in the mid 1990s. Was that congress could do pretty

much what ever it wanted under the commerce close. There wasn’t any real enforcement of

federalism limitations in this area. We are now in a different era, with a more

aggressive, robust Supreme Court, where at least five justices on the current

Court maintain that there are limits to national government power and that

the Court aught to enforce those limits.

And we saw such a case just

two years ago with the major Affordable Care Act case of 2012,

where a slim majority of the Court felt that a key part of

that statute, the individual mandate, was beyond the Federal Government’s

authority on commerce clause grounds. Because it sought to legislate

in the Court’s view. People who weren’t doing anything but

sitting around. And indeed the entire validity

of the Affordable Care Act was only upheld on a different ground

the so-called taxing power. Because the the burden or

the penalty that falls on people who didn’t pay the individual mandate is

operational as through their tax returns.

The Supreme Court found that the Affordable Care Act could not be upheld based on the Commerce Clause because what the Act was doing – asking people to buy health insurance – did not really affect interstate commerce. The Act could be upheld as an exercise of Congress’s taxing power.

So we’re in an era now where federal

government authority is vast but the Supreme Court assertively maintains

its prerogative to enforce that. There are many scholars and many in the

policy world who feel that these kind of federalism restrictions to control federal

government overreaching are important but ought not be enforced

by the Supreme Court. Indeed keep in mind the structural

provisions that are built into the so-called political branches,

that are built into Congress itself. and, and the argument goes includes

plenty of protections for the states. Each state gets two votes in the Senate. No matter how big or how small. So that a state like Wyoming has as much

representation on a state-by-state basis as a state like California. Despite vast discrepancies in population. For many observers, this suggests

that state interests are fully protected in the actual voting procedures

and political process in Congress, and that the Supreme Court ought not get

involved, in policing this boundary. It ought to stick to protecting

individual rights and standing up for the rights of entities and

individuals who don’t have a voice in the political process,

whereas states do have such a voice.

But clearly, as a statement of

current constitutional law, the Supreme Court has come out

strongly in the other direction, saying that it can and will enforce

these federalism restrictions.

I’ll now speak about a different

element of separation of powers. Now, in here we’re talking about the

horizontal separation of powers between the different branches of

the national government. This is the area where both today and historically Supreme Court

doctrine has been least helpful. I think precisely because

the fundamental definitions of these different branches are so

unspecified. Legislative power, executive power, judicial power

are undefined in the Constitution. And the precise contours and,

and boundaries of those concepts have become evermore

muddled as the government has grown, and changed, and become more complicated. For instance,

take an agency like the Food and Drug Agency, which regulates the safety

of food and therapeutic products,. The FDA is an executive branch agency. We know it is within the executive branch

but if we look at its functions it does some things that look like

executive enforcing of the laws. It had the authority to inspect and

enforce rules, say, against pharmaceutical manufacturers. But some of what it does looks

a lot more like a legislature. Like many agencies,

the FDA has authority to write rules which are binding and generally applicable and

look a lot like statutes. We call them regulations and thus place

them in the executive branch, but functionally, that behavior

looks much more legislative. Other agencies have the ability to

adjudicate actual cases and disputes. For instance the Social Security

Administration has its own judges who hear debates, or

hear disputes when somebody claims to be denied the proper amount

of benefits exercising very much a judicial function again despite

technically being in the executive branch.

For this reason,

the growth of government in ways that the framers never could have intended

have put pressure on these basic definitions inherent in the horizontal

separation of powers and confounded easy judicial techniques for drawing

bright lines between such branches. Today in this area courts are struggling

with issues like national security surveillance by the executive branch

the power of the President to wage war in foreign countries despite

not formally declaring war and the growth of congressional behavior and

congressional oversight activities which raise questions

about congressional overreaching. In these areas, there’s a real question

of how much the Supreme Court, or any judges can do,

to meaningfully police these boundaries. As I’ve said, the fundamental definitions

in the Constitution are so vague and unspecified, between executive,

legislative, and judicial power. That, articulating meaningful

doctrinal standards to channel and cabin these different types of

power have proven over the past two centuries to be largely unworkable.

Moreover many of these decisions,

such as whether or not to send troops to a foreign

country are probably the worse kind of decisions to vest in a group of unelected

judges who take a long time to hear cases. And perhaps ought to be worked out

more within the political process. Certainly James Madison and the other

framers envisioned that Congress and the President would be their

own best check on each other. That Congress would check

the President when he or she overreaches, and that the President

would check or refuse to enforce or would veto congressional laws that

represent where we are reaching. In here I will return to though a problem

that the framers never foresaw but that is essential part of our political

community today which is the rise of disciplined fairly powerful

political parties. Although, the framers envisioned politics. They didn’t in, view,

vision political parties. And, the notion of a strong disciplined

party controlling both Congress and the White House, undermines many of the

structural protections that Madison and the other framers thought would

work to control over-reaching. Simply put, when the President and Congress are of the same

party who will rein in an overreaching President if the President

indeed is the leader of his, his party? And we’ve seen, seen examples. Whatever political party or persuasion

one is, you can think of examples when Republican presidents have seemed to exert

dramatic authority unchecked by Congress. And you can think of recent examples

of a Democratic presidents have seem to exert unusually robust authority

largely unchecked by Congress. This is something

the framers never foresaw. And it’s a fundamental feature of our

political process which puts pressure. And perhaps stretches

to the breaking point. Some of the basic allocations of

authority in in the national government.

These are problems for which the court

probably doesn’ have a solution and it’s up to the rest of our

constitutional culture and other institutions: the public,

the president and congress. Perhaps working together going forward

to better structure and allocate power. This is not an area where an easy

doctrinal solution exists. So to sum up this entire

separation of powers discussion, I think we see two very different problems,

or two very different phenomenon. In the, in the Federalism context

the debate between state and federal authority and

in the horizontal separation of powers, context arrayed across

the federal government. When it comes to judicial control of

national government authority vis-a-vis the states, the current Supreme Court

has been very assertive, very robust and articulated very clear rules. In ways that many think have gone too

far in asserting judicial protection. On the other hand, when it comes

to presidential authority and overreaching many feel that the court

has not done enough to articulate clear meaningful standards to cabin executive

power in the 21st century, as it grows in ways that the framers never would

have imagined over two centuries ago. So these are the two competing

challenges in this area, that the court. And the rest of our constitutional culture

we’ll need to address going forward. [MUSIC]

Constitutional Law: Part 3

[MUSIC] This next part addresses a part of

the Constitution that many people think of first and foremost when they think

about the American Constitution and the protections that it affords. And here I’m talking

about individual rights. Rights such as freedom of speech,

freedom of religion, the right to be free of

discrimination based on race the protections that one

has as a criminal defendant. These are the rights which many people

associate most predominantly with constitutionalism and constitutional

protection and they are a part of the American constitutional order that

was there almost from the beginning, but has developed in dramatic fashion

over the past 50 or 60 years. The regime we have today for protecting individual rights looks

dramatically different than it did 100 years ago, and certainly dramatically

different than it did 200 years ago. This is a subject which can, and in, at many law schools does occupy

an entire semester long course but here, rather than focus on specific individual

rights, I want to draw together and emphasize some general themes that I

think, situate the individual rights jurisprudence of the American

Constitutional order within the longer textual and historical tradition that I’ve

been talking about during this segment.

And I can focus on a few

major points along this line. First, as I’ve alluded to before,

the text of the constitution vis a vis individual rights, just like it is

in other sections is remarkably sparse and undefined and, the mere words on

the page don’t do the work in protecting individual rights that our constitutional

culture has come to want them to do, and I’ll offer some examples here. Second this is an area where we’ve

seen dramatic changes over time in the national enforcement of

individual rights guarantees. Our constitutional world is fundamentally

different today that it was a century ago and changing even year by year, decade, decade by decade

in some ways I’ll discuss. Third, I want to address two fundamental

general doctrinal innovations that the Supreme Court has operationalized

over the past century in building the Constitution of

individual rights that we have today. The first of these is

the concept of incorporation, the idea that rights which as written

in the document’s text apply and constrain only the national government,

have been made applicable and universalized within the American

constitutional order to bind all government actors,

national, state and local.

Next, another general doctrinal device

which is quite important is the concept of balancing, or a nuanced standard of

review, that the justices apply in particular cases across a wide range

of individual rights areas: race discrimination, sex discrimination,

religious freedom freedom of expression. And here, the basic notion is that

no individual right is absolute. In the, in our constitutional discourse

the claims of individual rights holders are and must be balanced against

compelling claims by society at large for a different result. And this in, to a large, great extent, is the project of American constitutional

law in the individual rights space. It is the specification of which rights

are worthy of special protection that, there, then, that therefore,

demand especially good or compelling reasons from the government

in order to affect those rights. And its this shifting denomination of

which rights are important enough to, to demand particularly good reasons from

the government that is a large part of what the judges have done in, in construing the Constitution over

the past half century or more. Fourth, I’ll briefly address what’s

evident when one considers the development of individual rights doctrines

over the past several decades, the somewhat permial, permeable boundaries

between formal constitutional doctrine and public opinion about those rights.

Simply put, as society decides that

protecting a given interest is relatively more important, we would expect to see and

we do see doctrinal shifts in the judicial protection, the constitutional

protection for these rights. Nowhere is this more evident than in

the dramatic change in the manner in which the courts protect rights for certain

same-sex individuals, or even individuals to engage in same-sex relationships, and

I’ll speak for a few minutes about that. finally, as important as the Supreme Court

has been and still is in protecting individual rights, there

are those who wonder, and, and a question that’s worth posing is, is the court too

powerful or too supreme in this area? A question to consider is whether our

rights would be even more firmly grounded if we asked and expected legislatures,

executive officials, police departments, and other institutional actors

to take seriously these rights, instead of leaving them for

judicial resolution.

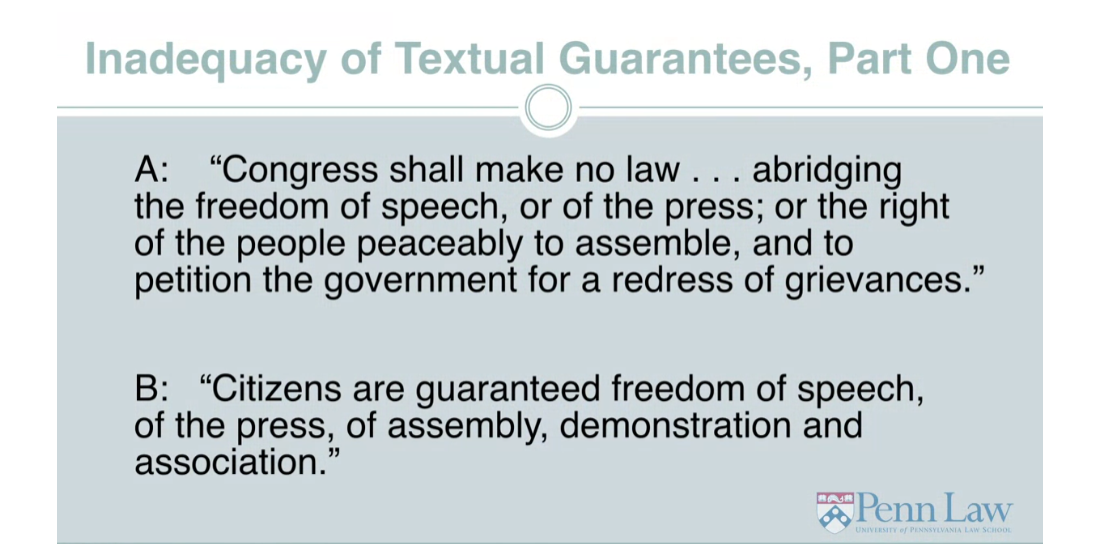

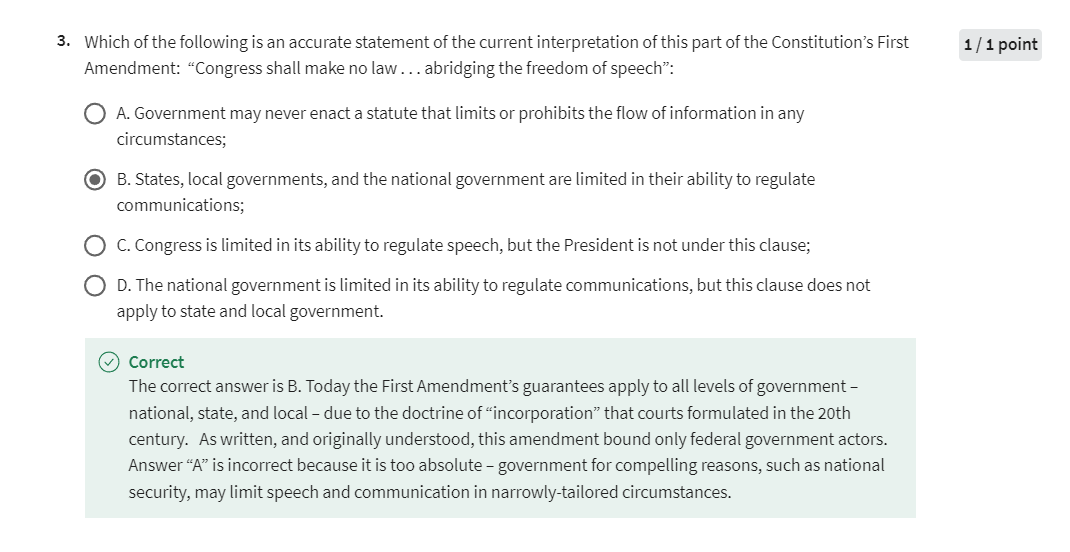

I’ll address all of these briefly in turn. First, let me turn to the concept of how

inadequate text is sitting on the page alone and here I’m going to use

two textual guarantees of rights. The first here, Congress shall make no

law abridging the freedom of speech, or the press; or the right of people

peaceably to assemble, and to petition the government for

a redress of grievances may be familiar to some of you if you’ve

read the US Constitution. This comes right out of

the First Amendment of our Constitution. Now the second clause here looks good,

as well. Citizens are guaranteed freedom of speech,

of the press, of assembly, demonstration and association.

This seems to protect the same freedoms,

indeed it was likely modeled, on the United States First Amendment

as it came afterwards. The second clause I read, labeled as

B on the slide, actually comes from the North Korea constitution, where we

know that despite these paper protections, citizens dramatically do not have the same

protections as they do elsewhere. And this is a vivid and perhaps almost too

extreme example of the disconnect between mere words on a page and the institutional

and cultural protection of those rights. If the North Korea example seems extreme,

I’ll turn to a more accurate historical example from

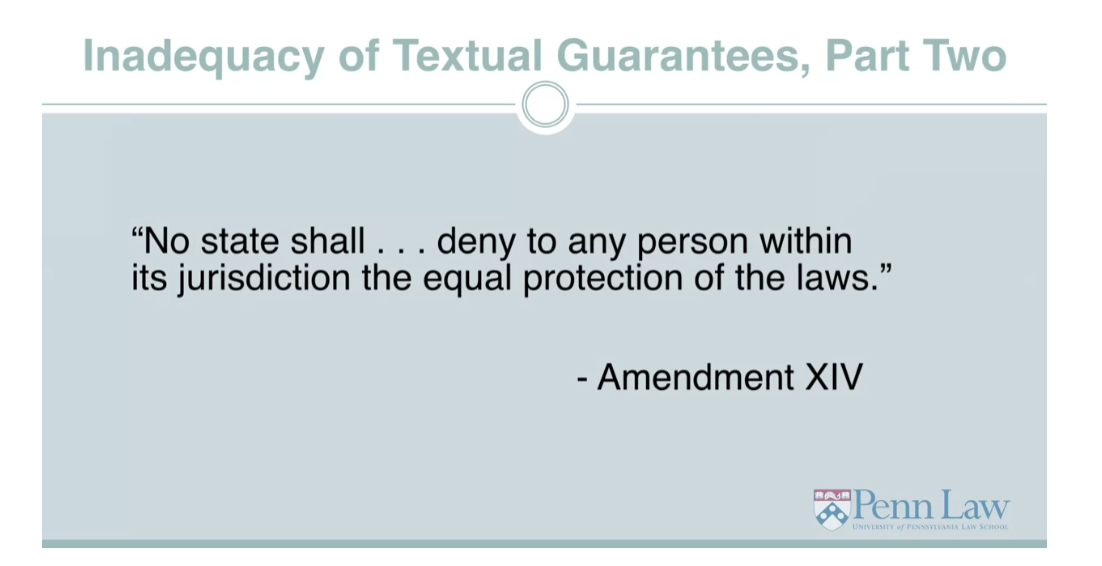

our own constitutional development. This text comes from our own Constitution,

the 14th amendment, we call this the equal protection clause. No state shall deny to any person within

its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.

It today is on, one of the most

fundamental personal protections against government discrimination and it forms a

core fabric of our Constitutional rights. This amendment was enacted in

the immediate aftermath of the Civil War, in the late 1860s and so

it has been on the books for almost 150 years as the Constitutional

law of the land of the United States. Now, as our history shows, for the majority of this amendment’s life,

these words were as unenforced as the words of the North Korean Constitution

I showed you a few minutes ago. These words were on our books through a

period in the early, late 19th century and early 20th century of brutal oppression

and Jim Crow segregation in the South and, dramatic discrimination against African

Americans throughout the entire country. As these examples illustrate,

words on the page by themselves, are inadequate protections

of personal freedoms.

What is needed is a more thick

institutional culture of enforcement and acceptance, to operationalize those words. To illustrate this point further I’ll use

the words of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., very early in his life actually as a high

school student when he gave an award winning speech precisely on this issue

of the empty promise of amendments on the pages of the Constitution

without more effective enforcement. King said America gave its full

pledge of freedom 75 years ago and backed it with amendments to the national

constitution where there should no discrimination based on race or

other criteria.

But as King notes, Black America,

in his, in, on this writing, Black America still wears chains. Thirteen million black sons and daughters

of our forefathers continue to fight for the translation of the thirteenth,

fourteenth, and fifteenth amendments from writing

on the printed page to actuality.

It’s this notion of translation that has

been a theme of this segment be it whe, whether it be in the separation of powers

area or this individual rights area. The words on the page don’t

interpret themselves and they certainly don’t enforce themselves. That requires an ongoing and

evolving societal commitment.

And this is what King both was

writing about in the 1940s and then participated in transforming and translating the meaning of the fourteenth

amendment into actual legislation and actual court decisions,

through the remainder of his life. I’ll now address two specific doctrinal

areas where the Supreme Court has constructed interpretive techniques and doctrines to engage in this project of

translation, that Dr. King spoke about. Without going into specific

areas like freedom of speech, or freedom of religion, or

criminal protections for criminal defendants, I’m focusing on two

general points that apply broadly across the landscape of individual rights in

the American Constitutional context. The first of these is this

idea of incorporation.

Incorporation is what

the Supreme Court did from the 1925, the 1920s through the 1960s

in order to universalize many of the most important individual rights

protections in our constitutional order. If you look at the Constitution’s text,

and here’s an example of the first

amendment it quite clearly says, Congress shall pass no law affecting

freedom of speech, press, etc. now, if one reads this literally,

one would think that only federal statutes must comply with First Amendment

scrutiny, that, say, state laws or local police enforcement could transgress

religious freedoms protection or throw people in jail for writing something

in the media, and indeed, if one reads the text ab, absolutely literally,

it applies only to the National Congress. But of course,

that’s not the way we’ve read it or understand it in our society and have not

read it that way for almost a century. And this relates to

the notion of incorporation. What the Supreme Court did starting in

the early 20th century, was take certain basic guarantees,

like the First Amendment, which, by its terms, appears to apply only

to Congress and incorporate, or fold that into our concept of due process

of law, which through the 14th Amendment, applies to all governments, state,

local, and as well as national. And the Supreme Court did this for many,

indeed most of the core individual rights protections that we hold dear that protect

defendants in criminal trials, that protect freedom of religion, that protect

our freedom of speech and association.

And then the Supreme Court likewise

universalized the Equal Protection clause, which by its terms is written

only to govern states, and said that the national

government likewise has to abide by the core anti-discrimination

principles of the Equal Protection clause. So what the Court did through its process

of incorporation that took place over the better part of the half of the 20th

century was to universalize and operationalize the core

individual rights guarantees in the constitution which again,

by the text alone, would have seemed to apply only to

certain governments and not others. Today, the individual protections

that are most important to Americans apply as against all levels of

government, national, state, or local. And the core, the basic core of

individual rights guaranteed in the Constitution applies equally across

the nation and, and doesn’t vary, at least in terms of the National

Constitution, from state to state. So this was a key judicial move that

was unforeseen by the framers, but that has done, a great deal to operationalize the culture

of individual rights that we have today.

The other core judicial innovation that I

want to emphasize in that it spans a wide swath of individual rights doctrines is

the way in which the court, particularly in the late 20th century through today,

has articulated different levels of scrutiny and different levels of balancing

individual rights against other interests. One of things, one of the things that’s

clear when one thinks about individual rights is that no matter how

important a given individual right is that right becomes problematic when

it is applied in an absolute sense to an extreme at the expense of all other

rights or all other public values.

We live in a complex world where

often there are difficult and fundamental trade-offs between, for

instance the widely held desire for privacy in our personal communications and

the equally widely held desire for national security and defense against

threats that demand a certain tradeoff. We value freedom of religion deeply, but we also realize that there are certain

commitments and behaviors that we need to regulate universally in society

and not allow religious exemption. This fundamental tension is

generates much of the debates in, about individual rights in

our in our legal culture. And in response justices on the Supreme

Court over the past half century or more have articulated a set of

doctrines which apply broadly across individual rights that attempt to balance

these different competing considerations. And we think of these

as levels of scrutiny. The basic principle is that most of

the things government wants to do, it can justify against lawsuits if it

can articulate a merely rational basis. Essentially, as long as it

can give any decent reason it can justify a distinction it makes. So for instance the government

in its tax code draws lots of distinctions between how

certain things are taxed or different levels of tax that some

people pay as opposed to another. Clearly it creates inequality. But that inequality is not,

according to judges and others who participate in

constitutional interpretation, is not the kind of equality that

we ought to care deeply about, and to say we care deeply about in

a doctrinal sense, is to say we give certain problematic dimensions of

inequality, we give them strict scrutiny. What strict scrutiny means is,

and an example would be, when the government treats people

of different races differently, we are going to apply

the strictest possible scrutiny, given the problematic history

of racial differentiation. It doesn’t mean the government can never

differentiate on race, it just means that the government better have an especially

good, or compelling, reason for doing so.

Tiers of Scrutiny: the tests

- Rational basis: the government has any decent reason for drawing a certain distinction

- Strict scrutiny: government must have an especially good or compelling reason for drawing a certain distinction

- Intermediate scrutiny: in between

Tiers of Scrutiny: when they apply

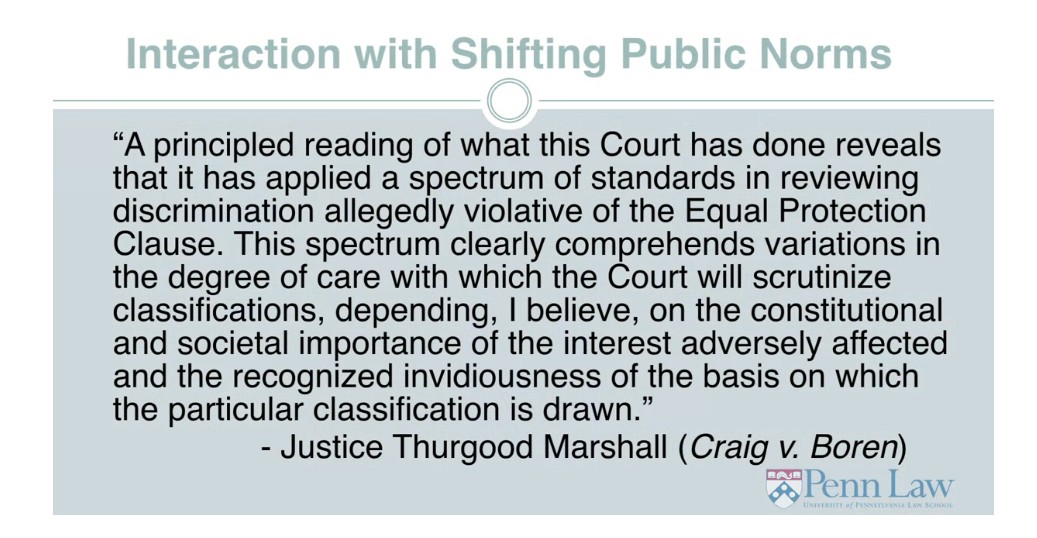

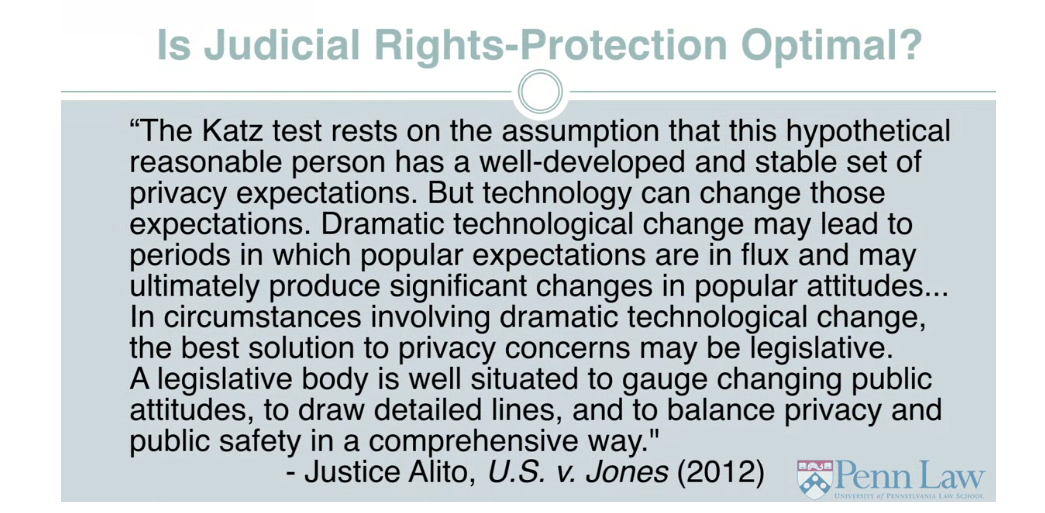

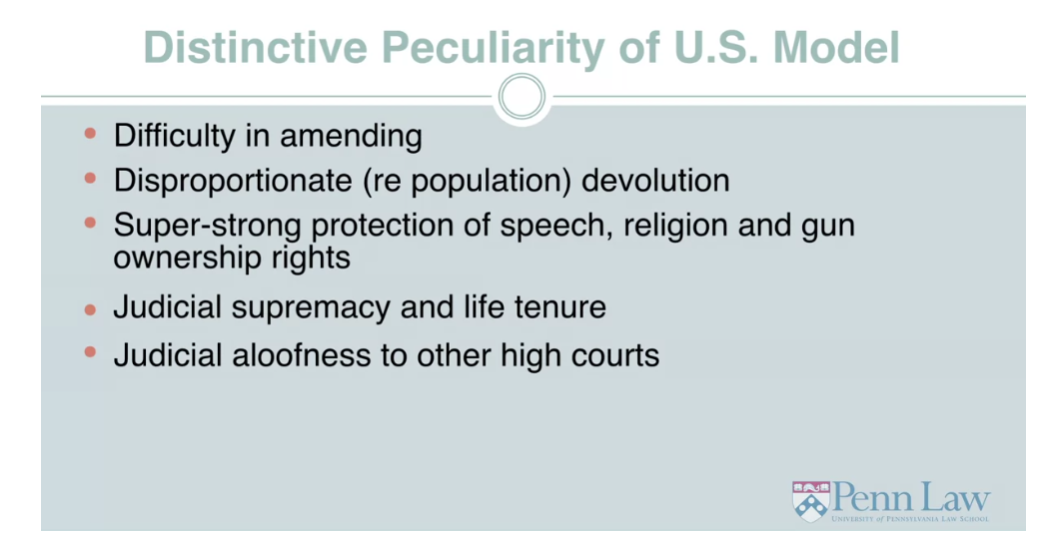

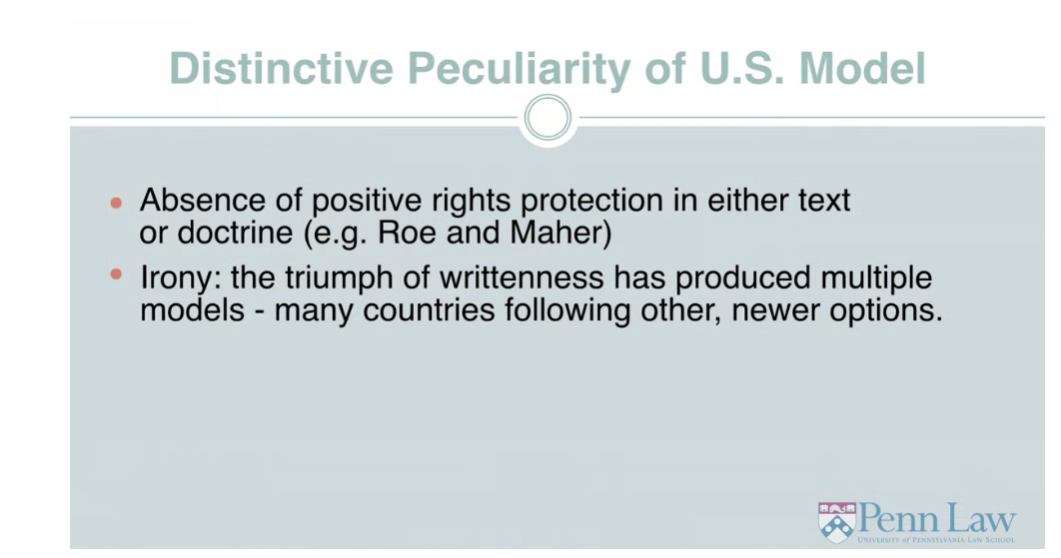

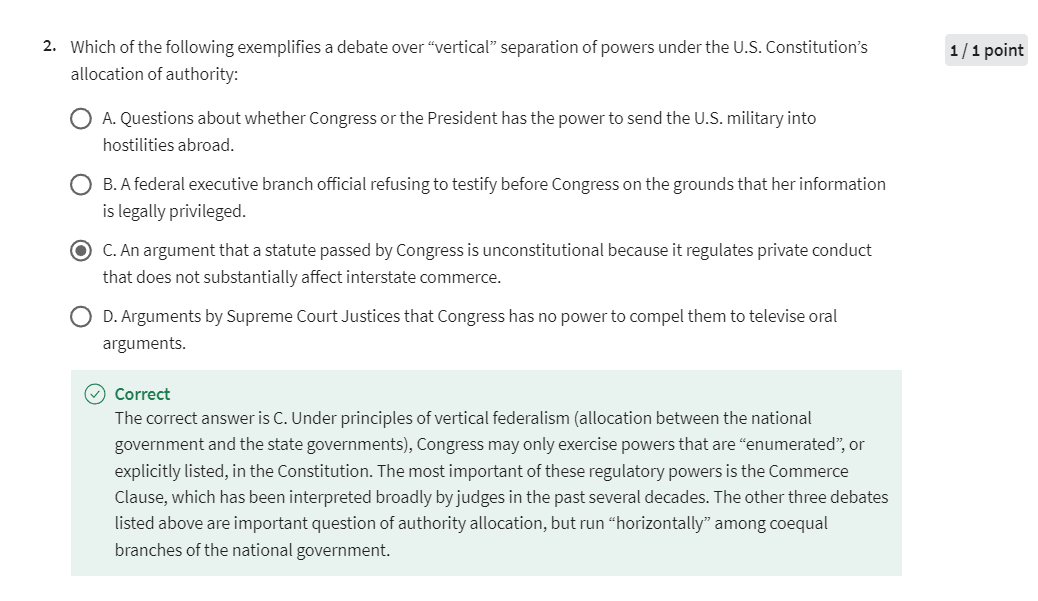

- Rational basis: most government actions