Makefile详细教程

我编写本指南是因为我永远无法完全理解 Makefile。 他们似乎充斥着隐藏的规则和深奥的符号,提出简单的问题并没有得到简单的答案。 为了解决这个问题,我花了几个周末的时间坐下来阅读所有关于 Makefile 的内容。 我已将最关键的知识浓缩到本指南中。 每个主题都有一个简短的描述和一个您可以自己运行的独立示例。

文章目录

- Makefile详细教程

- 入门

- Make 有哪些替代方案?

- Make的版本和类型

- 运行示例

- 生成文件语法

- Make的本质

- 更多快速示例

- clean

- 变量

- Targets

- all Targets

- 多个目标

- 自动变量和通配符

- `*` 通配符

- `%` 通配符

- 自动变量

- 花式规则

- 隐式规则

- 静态模式规则

- 静态模式规则和过滤器

- 模式规则

- 双冒号规则

- 命令和执行

- 命令回显/静音

- 命令执行

- 默认shell

- 双美元符号

- 使用 -k、-i 和 - 进行错误处理

- 中断或杀死 make

- make的递归使用

- 导出、环境和递归 make

- Make参数

- 变量2

- 风格和修改

- 命令行参数和覆盖

- 命令列表和定义

- 特定于目标的变量

- 特定于模式的变量

- Makefile 的条件部分

- 条件if/else

- 检查变量是否为空

- 检查变量是否定义

- `$(makeflags)`

- 函数

- 第一个函数

- 字符串替换

- foreach函数

- if函数

- 调用函数

- shell函数

- 其他特性

- include Makefile

- vpath 指令

- 多行

- .PHONY

- .delete_on_error

- 生成文件

入门

为什么存在 Makefile?

Makefile 用于帮助决定大型程序的哪些部分需要重新编译。 在绝大多数情况下,编译 C 或 C++ 文件。 其他语言通常有自己的工具,其目的与 Make 类似。 当您需要根据更改的文件运行一系列指令时,Make 也可以在编译之外使用。 本教程将重点关注 C/C++ 编译用例。

下面是您可以使用 Make 构建的示例依赖关系图。 如果任何文件的依赖关系发生变化,那么该文件将被重新编译:

Make 有哪些替代方案?

流行的 C/C++ 替代构建系统是 SCons、CMake、Bazel 和 Ninja。 某些代码编辑器(如 Microsoft Visual Studio)有自己的内置构建工具。 对于 Java,有 Ant、Maven 和 Gradle。 Go 和 Rust 等其他语言都有自己的构建工具。

Python、Ruby 和 Javascript 等解释型语言不需要 Makefile 的类似物。 Makefile 的目标是根据已更改的文件来编译需要编译的任何文件。 但是当解释性语言的文件发生变化时,不需要重新编译。 程序运行时,将使用最新版本的文件。

Make的版本和类型

Make 有多种实现方式,但本指南的大部分内容都适用于您使用的任何版本。 但是,它是专门为 GNU Make 编写的,它是 Linux 和 MacOS 上的标准实现。 所有示例都适用于 Make 版本 3 和 4,除了一些深奥的差异外,它们几乎相同。

运行示例

要运行这些示例,您需要一个终端并安装“make”。 对于每个示例,将内容放入一个名为 Makefile 的文件中,然后在该目录中运行命令 make。 让我们从最简单的 Makefile 开始:

hello:

echo "Hello, World"

注意:Makefile 必须使用制表符而不是空格缩进,否则 make 将失败。

以下是运行上述示例的输出:

$ make

echo "Hello, World"

Hello, World

生成文件语法

Makefile 由一组规则组成。 规则通常如下所示:

targets: prerequisites

command

command

command

- targets是文件名,以空格分隔。 通常,每个规则只有一个。

- command是通常用于制作目标的一系列步骤。 这些需要以制表符而不是空格开头。

- prerequisites也是文件名,以空格分隔。 在运行针对目标的命令之前,这些文件需要存在。 这些也称为依赖项

Make的本质

让我们从一个Hello, World例子开始:

hello:

echo "Hello, World"

echo "This line will always print, because the file hello does not exist."

这里已经有很多东西可以吸收了。 让我们分解一下:

- 我们有一个名为 hello 的目标

- 这个目标有两个命令

- 这个目标没有先决条件

然后我们将运行 make hello。 只要 hello 文件不存在,命令就会运行。 如果 hello 确实存在,则不会运行任何命令。

重要的是要意识到我是在谈论 hello 既是目标又是文件。 那是因为两者是直接捆绑在一起的。 通常,当目标运行时(也就是运行目标的命令时),这些命令将创建一个与目标同名的文件。 在这种情况下,hello 目标不会创建 hello 文件。

让我们创建一个更典型的 Makefile - 一个编译单个 C 文件的文件。 但在我们这样做之前,创建一个名为 blah.c 的文件,其中包含以下内容:

// blah.c

int main() { return 0; }

然后创建 Makefile(一如既往地称为 Makefile):

blah:

cc blah.c -o blah

这一次,尝试简单地运行 make。 由于没有目标作为参数提供给 make 命令,因此运行第一个目标。 在这种情况下,只有一个目标(废话)。 第一次运行它时,将创建 blah。 第二次,您会看到 make: ‘blah’ 是最新的。 那是因为 blah 文件已经存在。 但是有一个问题:如果我们修改 blah.c 然后运行 make,则不会重新编译任何东西。

我们通过添加一个先决条件来解决这个问题:

blah: blah.c

cc blah.c -o blah

当我们再次运行 make 时,会发生以下一组步骤:

- 选择第一个目标,因为第一个目标是默认目标

- 这有 blah.c 的先决条件

- Make 决定是否应该运行 blah 目标。 它只会在 blah 不存在时运行,或者 blah.c 比 blah 更新

最后一步很关键,是 make 的本质。 它试图做的是确定自上次编译 blah 以来 blah 的先决条件是否发生了变化。 也就是说,如果 blah.c 被修改,运行 make 应该重新编译该文件。 相反,如果 blah.c 没有改变,那么它不应该被重新编译。

为了实现这一点,它使用文件系统时间戳作为代理来确定是否发生了某些变化。 这是一种合理的启发式方法,因为文件时间戳通常只会在文件被修改时发生变化。 但重要的是要认识到情况并非总是如此。 例如,您可以修改一个文件,然后将该文件的修改时间戳更改为旧的时间戳。 如果你这样做了,Make 会错误地猜测文件没有改变,因此可以被忽略。

确保您了解这一点。 它是 Makefile 的关键,您可能需要几分钟才能正确理解。

更多快速示例

下面的 Makefile 最终运行所有三个目标。 当您在终端中运行 make 时,它将通过一系列步骤构建一个名为 blah 的程序:

- Make 选择目标 blah,因为第一个目标是默认目标

blah需要blah.o,所以搜索blah.o目标blah.o需要blah.c,因此搜索blah.c目标blah.c没有依赖关系,所以运行 echo 命令- 然后运行 cc -c 命令,因为所有

blah.o依赖项都已完成 - cc 命令运行,因为所有的 blah 依赖都完成了

- 就是这样:blah 是一个已编译的 C 程序

blah: blah.o

cc blah.o -o blah # Runs third

blah.o: blah.c

cc -c blah.c -o blah.o # Runs second

# Typically blah.c would already exist, but I want to limit any additional required files

blah.c:

echo "int main() { return 0; }" > blah.c # Runs first

如果删除 blah.c,所有三个目标都将重新运行。 如果您编辑它(并因此将时间戳更改为比 blah.o 更新),前两个目标将运行。 如果您运行 touch blah.o(并因此将时间戳更改为比 blah 更新),则只有第一个目标会运行。 如果您不做任何更改,则所有目标都不会运行。 试试看!

下一个示例没有做任何新的事情,但仍然是一个很好的附加示例。 它将始终运行两个目标,因为 some_file 依赖于永远不会创建的 other_file。

some_file: other_file

echo "This will always run, and runs second"

touch some_file

other_file:

echo "This will always run, and runs first"

clean

clean 经常被用作去除其他目标输出的目标,但它不是 Make 中的特殊词。 您可以在此运行 make 和 make clean 来创建和删除 some_file。

请注意,clean 在这里做了两件新事情:

- 它不是第一个目标(默认),也不是先决条件。 这意味着它永远不会运行,除非您明确调用

make clean - 它不是一个文件名。 如果你碰巧有一个名为 clean 的文件,这个目标将不会运行,这不是我们想要的。 有关如何解决此问题的信息,请参阅本教程后面的

.PHONY

some_file:

touch some_file

clean:

rm -f some_file

变量

变量只能是字符串。 您通常希望使用 :=,但 = 也可以。

下面是一个使用变量的例子:

files := file1 file2

some_file: $(files)

echo "Look at this variable: " $(files)

touch some_file

file1:

touch file1

file2:

touch file2

clean:

rm -f file1 file2 some_file

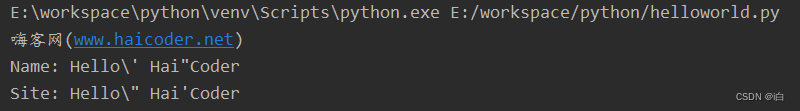

单引号或双引号对 Make 没有意义。 它们只是分配给变量的字符。 不过,引号对 shell/bash 很有用,您在 printf 等命令中需要它们。 在此示例中,这两个命令的行为相同:

a := one two # a is assigned to the string "one two"

b := 'one two' # Not recommended. b is assigned to the string "'one two'"

all:

printf '$a'

printf $b

使用 ${} 或 $() 引用变量

x := dude

all:

echo $(x)

echo ${x}

# Bad practice, but works

echo $x

Targets

all Targets

制定多个目标并希望所有目标都运行? 制定一个全部目标。 由于这是列出的第一条规则,如果在未指定目标的情况下调用 make,它将默认运行。

all: one two three

one:

touch one

two:

touch two

three:

touch three

clean:

rm -f one two three

多个目标

当规则有多个目标时,将为每个目标运行命令。 $@ 是一个包含目标名称的自动变量。

all: f1.o f2.o

f1.o f2.o:

echo $@

# Equivalent to:

# f1.o:

# echo f1.o

# f2.o:

# echo f2.o

自动变量和通配符

* 通配符

* 和 % 在 Make 中都被称为通配符,但它们的含义完全不同。 * 在您的文件系统中搜索匹配的文件名。 我建议您始终将它包装在通配符函数中,否则您可能会陷入下面描述的常见陷阱。

# Print out file information about every .c file

print: $(wildcard *.c)

ls -la $?

* 可以在目标、先决条件或通配符函数中使用。

危险:* 不能直接用在变量定义中

危险:当*没有匹配到任何文件时,保持原样(除非在通配符函数中运行)

thing_wrong := *.o # Don't do this! '*' will not get expanded

thing_right := $(wildcard *.o)

all: one two three four

# Fails, because $(thing_wrong) is the string "*.o"

one: $(thing_wrong)

# Stays as *.o if there are no files that match this pattern :(

two: *.o

# Works as you would expect! In this case, it does nothing.

three: $(thing_right)

# Same as rule three

four: $(wildcard *.o)

% 通配符

% 确实很有用,但由于它可用于多种情况,所以有点令人困惑。

- 在“匹配”模式下使用时,它匹配字符串中的一个或多个字符。 这种匹配称为stem。

- 在“替换”模式下使用时,它采用匹配的词干并替换字符串中的词干。

%最常用于规则定义和某些特定函数中。

自动变量

有很多自动变量,但通常只有少数几个会出现:

hey: one two

# Outputs "hey", since this is the target name

echo $@

# Outputs all prerequisites newer than the target

echo $?

# Outputs all prerequisites

echo $^

touch hey

one:

touch one

two:

touch two

clean:

rm -f hey one two

花式规则

隐式规则

每次让Makefile它表达爱意时,事情都会变得扑朔迷离。 也许 Make 最令人困惑的部分是制定的花式/自动规则。 调用这些“隐式”规则。 我个人不同意这个设计决定,也不推荐使用它们,但它们经常被使用,因此了解它们很有用。 这是隐式规则的列表:

- 编译 C 程序:

n.o是通过 $(CC) -c $(CPPFLAGS) $(CFLAGS) $^ -o $@形式的命令从n.c自动生成的 - 编译 C++ 程序:

n.o是通过$(CXX) -c $(CPPFLAGS) $(CXXFLAGS) $^ -o $@形式的命令从n.cc或n.cpp自动生成的 - 链接单个目标文件:通过运行命令

$(CC) $(LDFLAGS) $^ $(LOADLIBES) $(LDLIBS) -o $@自动从n.o生成n

隐式规则使用的重要变量是:

- CC:用于编译C程序的程序; 默认抄送

- CXX:编译C++程序的程序; 默认 g++

- CFLAGS:提供给 C 编译器的额外标志

- CXXFLAGS:提供给 C++ 编译器的额外标志

- CPPFLAGS:提供给 C 预处理器的额外标志

- LDFLAGS:当编译器应该调用链接器时提供给编译器的额外标志

让我们看看我们现在如何构建一个 C 程序,而无需明确告诉 Make 如何进行编译:

CC = gcc # Flag for implicit rules

CFLAGS = -g # Flag for implicit rules. Turn on debug info

# Implicit rule #1: blah is built via the C linker implicit rule

# Implicit rule #2: blah.o is built via the C compilation implicit rule, because blah.c exists

blah: blah.o

blah.c:

echo "int main() { return 0; }" > blah.c

clean:

rm -f blah*

静态模式规则

静态模式规则是另一种在 Makefile 中编写更少的方法,但我认为它更有用并且不那么“神奇”。 这是它们的语法:

targets...: target-pattern: prereq-patterns ...

commands

本质是给定的目标与目标模式匹配(通过 % 通配符)。 匹配的任何内容都称为词干。 然后将词干替换到先决条件模式中,以生成目标的先决条件。

一个典型的用例是将 .c 文件编译成 .o 文件。 这是手动方式:

objects = foo.o bar.o all.o

all: $(objects)

# These files compile via implicit rules

foo.o: foo.c

bar.o: bar.c

all.o: all.c

all.c:

echo "int main() { return 0; }" > all.c

%.c:

touch $@

clean:

rm -f *.c *.o all

这是更有效的方法,使用静态模式规则:

objects = foo.o bar.o all.o

all: $(objects)

# These files compile via implicit rules

# Syntax - targets ...: target-pattern: prereq-patterns ...

# In the case of the first target, foo.o, the target-pattern matches foo.o and sets the "stem" to be "foo".

# It then replaces the '%' in prereq-patterns with that stem

$(objects): %.o: %.c

all.c:

echo "int main() { return 0; }" > all.c

%.c:

touch $@

clean:

rm -f *.c *.o all

静态模式规则和过滤器

当我稍后介绍函数时,我将预示您可以使用它们做什么。 过滤器功能可用于静态模式规则以匹配正确的文件。 在这个例子中,我制作了 .raw 和 .result 扩展名。

obj_files = foo.result bar.o lose.o

src_files = foo.raw bar.c lose.c

all: $(obj_files)

# Note: PHONY is important here. Without it, implicit rules will try to build the executable "all", since the prereqs are ".o" files.

.PHONY: all

# Ex 1: .o files depend on .c files. Though we don't actually make the .o file.

$(filter %.o,$(obj_files)): %.o: %.c

echo "target: $@ prereq: $<"

# Ex 2: .result files depend on .raw files. Though we don't actually make the .result file.

$(filter %.result,$(obj_files)): %.result: %.raw

echo "target: $@ prereq: $<"

%.c %.raw:

touch $@

clean:

rm -f $(src_files)

模式规则

模式规则经常被使用但是很混乱。 您可以通过两种方式查看它们:

- 一种定义自己的隐式规则的方法

- 一种更简单的静态模式规则

让我们先从一个例子开始:

# Define a pattern rule that compiles every .c file into a .o file

%.o : %.c

$(CC) -c $(CFLAGS) $(CPPFLAGS) $< -o $@

模式规则在目标中包含“%”。 这个 '%' 匹配任何非空字符串,其他字符匹配它们自己。 模式规则先决条件中的“%”代表与目标中的“%”匹配的相同词干。

这是另一个例子:

# Define a pattern rule that has no pattern in the prerequisites.

# This just creates empty .c files when needed.

%.c:

touch $@

双冒号规则

双冒号规则很少使用,但允许为同一目标定义多个规则。 如果这些是单个冒号,则会打印一条警告,并且只会运行第二组命令。

all: blah

blah::

echo "hello"

blah::

echo "hello again"

命令和执行

命令回显/静音

在命令前添加 @ 以阻止它被打印

您还可以使用 -s 运行 make 以在每行之前添加一个 @

all:

@echo "This make line will not be printed"

echo "But this will"

命令执行

每个命令都在一个新的 shell 中运行(或者至少效果是这样的)

all:

cd ..

# The cd above does not affect this line, because each command is effectively run in a new shell

echo `pwd`

# This cd command affects the next because they are on the same line

cd ..;echo `pwd`

# Same as above

cd ..; \

echo `pwd`

默认shell

默认 shell 是 /bin/sh。 您可以通过更改变量 SHELL 来更改此设置:

SHELL=/bin/bash

cool:

echo "Hello from bash"

双美元符号

如果你想让一个字符串有一个美元符号,你可以使用 $$。 这是在 bash 或 sh 中使用 shell 变量的方法。

请注意下一个示例中 Makefile 变量和 Shell 变量之间的区别。

make_var = I am a make variable

all:

# Same as running "sh_var='I am a shell variable'; echo $sh_var" in the shell

sh_var='I am a shell variable'; echo $$sh_var

# Same as running "echo I am a amke variable" in the shell

echo $(make_var)

使用 -k、-i 和 - 进行错误处理

在运行 make 时添加 -k 以在遇到错误时继续运行。 如果您想立即查看 Make 的所有错误,这将很有帮助。

在命令前添加 - 以抑制错误

添加 -i 以使每个命令都发生这种情况。

one:

# This error will be printed but ignored, and make will continue to run

-false

touch one

中断或杀死 make

仅注意:如果您按 ctrl+c make,它将删除刚刚创建的较新目标。

make的递归使用

要递归调用 makefile,请使用特殊的 $(MAKE) 而不是 make,因为它会为您传递 make 标志,并且本身不会受到它们的影响。

new_contents = "hello:\n\ttouch inside_file"

all:

mkdir -p subdir

printf $(new_contents) | sed -e 's/^ //' > subdir/makefile

cd subdir && $(MAKE)

clean:

rm -rf subdir

导出、环境和递归 make

当 Make 启动时,它会根据执行时设置的所有环境变量自动创建 Make 变量

# Run this with "export shell_env_var='I am an environment variable'; make"

all:

# Print out the Shell variable

echo $$shell_env_var

# Print out the Make variable

echo $(shell_env_var)

导出指令采用一个变量并将其设置为所有配方中所有 shell 命令的环境:

shell_env_var=Shell env var, created inside of Make

export shell_env_var

all:

echo $(shell_env_var)

echo $$shell_env_var

因此,当您在 make 内部运行 make 命令时,您可以使用 export 指令使其可供子 make 命令访问。 在此示例中,导出了 cooly,以便 subdir 中的 makefile 可以使用它。

new_contents = "hello:\n\techo \$$(cooly)"

all:

mkdir -p subdir

printf $(new_contents) | sed -e 's/^ //' > subdir/makefile

@echo "---MAKEFILE CONTENTS---"

@cd subdir && cat makefile

@echo "---END MAKEFILE CONTENTS---"

cd subdir && $(MAKE)

# Note that variables and exports. They are set/affected globally.

cooly = "The subdirectory can see me!"

export cooly

# This would nullify the line above: unexport cooly

clean:

rm -rf subdir

您还需要导出变量才能让它们在 shell 中运行。

one=this will only work locally

export two=we can run subcommands with this

all:

@echo $(one)

@echo $$one

@echo $(two)

@echo $$two

.EXPORT_ALL_VARIABLES 为您导出所有变量。

.EXPORT_ALL_VARIABLES:

new_contents = "hello:\n\techo \$$(cooly)"

cooly = "The subdirectory can see me!"

# This would nullify the line above: unexport cooly

all:

mkdir -p subdir

printf $(new_contents) | sed -e 's/^ //' > subdir/makefile

@echo "---MAKEFILE CONTENTS---"

@cd subdir && cat makefile

@echo "---END MAKEFILE CONTENTS---"

cd subdir && $(MAKE)

clean:

rm -rf subdir

Make参数

有一个很好的选项列表可以从 make 运行。 查看 --dry-run、--touch、--old-file。

您可以制定多个目标,即 make clean run test 运行 clean 目标,然后运行,然后测试。

变量2

风格和修改

有两种类型的变量:

- 递归(使用 =) - 仅在使用命令时查找变量,而不是在定义时查找。

- 简单地扩展(使用 :=)——就像普通的命令式编程一样——只有到目前为止定义的那些才会被扩展

# Recursive variable. This will print "later" below

one = one ${later_variable}

# Simply expanded variable. This will not print "later" below

two := two ${later_variable}

later_variable = later

all:

echo $(one)

echo $(two)

简单扩展(使用 :=)允许您附加到变量。 递归定义会产生无限循环错误。

one = hello

# one gets defined as a simply expanded variable (:=) and thus can handle appending

one := ${one} there

all:

echo $(one)

?= 仅在尚未设置变量时设置变量

one = hello

one ?= will not be set

two ?= will be set

all:

echo $(one)

echo $(two)

一行末尾的空格不会被删除,但开头的空格会被删除。 要使用单个空格创建变量,请使用 $(nullstring)

with_spaces = hello # with_spaces has many spaces after "hello"

after = $(with_spaces)there

nullstring =

space = $(nullstring) # Make a variable with a single space.

all:

echo "$(after)"

echo start"$(space)"end

一个未定义的变量实际上是一个空字符串!

all:

# Undefined variables are just empty strings!

echo $(nowhere)

使用 += 追加

foo := start

foo += more

all:

echo $(foo)

字符串替换也是一种非常常见且有用的修改变量的方法。

命令行参数和覆盖

您可以使用 override 覆盖来自命令行的变量。 在这里我们用 make option_one=hi 运行 make

# Overrides command line arguments

override option_one = did_override

# Does not override command line arguments

option_two = not_override

all:

echo $(option_one)

echo $(option_two)

命令列表和定义

define 指令不是一个函数,尽管它可能看起来是这样。 我看到它很少使用,所以我不会详细介绍。

define/endef 只是创建一个分配给命令列表的变量。 请注意,这与在命令之间使用分号有点不同,因为正如预期的那样,每个命令都在单独的 shell 中运行。

one = export blah="I was set!"; echo $$blah

define two

export blah="I was set!"

echo $$blah

endef

all:

@echo "This prints 'I was set'"

@$(one)

@echo "This does not print 'I was set' because each command runs in a separate shell"

@$(two)

特定于目标的变量

可以为特定目标分配变量

all: one = cool

all:

echo one is defined: $(one)

other:

echo one is nothing: $(one)

特定于模式的变量

您可以为特定的目标模式分配变量

%.c: one = cool

blah.c:

echo one is defined: $(one)

other:

echo one is nothing: $(one)

Makefile 的条件部分

条件if/else

foo = ok

all:

ifeq ($(foo), ok)

echo "foo equals ok"

else

echo "nope"

endif

检查变量是否为空

nullstring =

foo = $(nullstring) # end of line; there is a space here

all:

ifeq ($(strip $(foo)),)

echo "foo is empty after being stripped"

endif

ifeq ($(nullstring),)

echo "nullstring doesn't even have spaces"

endif

检查变量是否定义

ifdef 不扩展变量引用; 它只是查看是否定义了某些内容

bar =

foo = $(bar)

all:

ifdef foo

echo "foo is defined"

endif

ifndef bar

echo "but bar is not"

endif

$(makeflags)

此示例向您展示如何使用 findstring 和 MAKEFLAGS 测试 make 标志。 使用 make -i 运行此示例以查看它打印出 echo 语句。

bar =

foo = $(bar)

all:

# Search for the "-i" flag. MAKEFLAGS is just a list of single characters, one per flag. So look for "i" in this case.

ifneq (,$(findstring i, $(MAKEFLAGS)))

echo "i was passed to MAKEFLAGS"

endif

函数

第一个函数

函数主要用于文本处理。 使用 $(fn, arguments) 或 ${fn, arguments} 调用函数。 您可以使用 call 内置函数创建自己的。 Make 有相当数量的内置函数。

bar := ${subst not, totally, "I am not superman"}

all:

@echo $(bar)

如果要替换空格或逗号,请使用变量

comma := ,

empty:=

space := $(empty) $(empty)

foo := a b c

bar := $(subst $(space),$(comma),$(foo))

all:

@echo $(bar)

不要在第一个之后的参数中包含空格。 这将被视为字符串的一部分。

comma := ,

empty:=

space := $(empty) $(empty)

foo := a b c

bar := $(subst $(space), $(comma) , $(foo))

all:

# Output is ", a , b , c". Notice the spaces introduced

@echo $(bar)

字符串替换

$(patsubst pattern,replacement,text) 执行以下操作:

“在匹配模式的文本中找到以空格分隔的词,并用替换替换它们。这里的模式可能包含一个‘%’,它充当通配符,匹配一个词中任意数量的任意字符。如果替换也包含‘%’, '%' 替换为与模式中的 '%' 匹配的文本。只有模式中的第一个 '%' 和替换以这种方式处理;任何后续的 '%' 都保持不变。” (GNU 文档)

替换引用 $(text:pattern=replacement) 是对此的简写。

还有另一种仅替换后缀的简写形式:$(text:suffix=replacement)。 这里没有使用 % 通配符。

注意:不要为此速记添加额外的空格。 它将被视为搜索或替换词。

foo := a.o b.o l.a c.o

one := $(patsubst %.o,%.c,$(foo))

# This is a shorthand for the above

two := $(foo:%.o=%.c)

# This is the suffix-only shorthand, and is also equivalent to the above.

three := $(foo:.o=.c)

all:

echo $(one)

echo $(two)

echo $(three)

foreach函数

foreach 函数如下所示:$(foreach var,list,text)。 它将一个单词列表(以空格分隔)转换为另一个单词列表。 var 设置为列表中的每个单词,并为每个单词扩展文本。

这会在每个单词后附加一个感叹号:

foo := who are you

# For each "word" in foo, output that same word with an exclamation after

bar := $(foreach wrd,$(foo),$(wrd)!)

all:

# Output is "who! are! you!"

@echo $(bar)

if函数

if 检查第一个参数是否为非空。 如果是,则运行第二个参数,否则运行第三个。

foo := $(if this-is-not-empty,then!,else!)

empty :=

bar := $(if $(empty),then!,else!)

all:

@echo $(foo)

@echo $(bar)

调用函数

Make 支持创建基本函数。 您仅通过创建一个变量来“定义”该函数,但使用参数 $(0)、$(1) 等。然后您使用特殊调用函数调用该函数。 语法是 $(call variable,param,param)。 $(0) 是变量,而 $(1)、$(2) 等是参数。

sweet_new_fn = Variable Name: $(0) First: $(1) Second: $(2) Empty Variable: $(3)

all:

# Outputs "Variable Name: sweet_new_fn First: go Second: tigers Empty Variable:"

@echo $(call sweet_new_fn, go, tigers)

shell函数

shell - 这会调用 shell,但它会用空格替换换行符!

all:

@echo $(shell ls -la) # Very ugly because the newlines are gone!

其他特性

include Makefile

include 指令告诉 make 读取一个或多个其他 makefile。 它是 makefile 中的一行,如下所示:

include filenames...

当您使用编译器标志(如 -M)基于源代码创建 Makefile 时,这尤其有用。 例如,如果某些 c 文件包含头文件,则该头文件将添加到由 gcc 编写的 Makefile 中。

vpath 指令

使用 vpath 指定存在某些先决条件集的位置。 格式为 vpath <pattern> <directories, space/colon separated> <pattern> 可以有一个 %,它匹配任何零个或多个字符。

您也可以使用变量 VPATH 全局执行此操作

vpath %.h ../headers ../other-directory

some_binary: ../headers blah.h

touch some_binary

../headers:

mkdir ../headers

blah.h:

touch ../headers/blah.h

clean:

rm -rf ../headers

rm -f some_binary

多行

反斜杠(“\”)字符使我们能够在命令太长时使用多行

some_file:

echo This line is too long, so \

it is broken up into multiple lines

.PHONY

将 .PHONY 添加到目标将防止 Make 将虚假目标与文件名混淆。 在此示例中,如果创建了文件 clean,make clean 仍将运行。 从技术上讲,我应该在每个带有 all 或 clean 的示例中都使用它,但我没有保持示例干净。 此外,“phony”目标的名称通常很少是文件名,实际上许多人会跳过这一点。

some_file:

touch some_file

touch clean

.PHONY: clean

clean:

rm -f some_file

rm -f clean

.delete_on_error

如果命令返回非零退出状态,make 工具将停止运行规则(并将传播回先决条件)。

如果规则以这种方式失败,则 DELETE_ON_ERROR 将删除规则的目标。 这将发生在所有目标上,而不仅仅是像 PHONY 之前的目标。 始终使用它是个好主意,即使由于历史原因 make 没有这样做。

.DELETE_ON_ERROR:

all: one two

one:

touch one

false

two:

touch two

false

生成文件

让我们来看一个非常有趣的 Make 示例,它适用于中型项目。

这个 makefile 的巧妙之处在于它会自动为您确定依赖项。 您所要做的就是将 C/C++ 文件放在 src/ 文件夹中。

TARGET_EXEC := final_program

BUILD_DIR := ./build

SRC_DIRS := ./src

# Find all the C and C++ files we want to compile

# Note the single quotes around the * expressions. Make will incorrectly expand these otherwise.

SRCS := $(shell find $(SRC_DIRS) -name '*.cpp' -or -name '*.c' -or -name '*.s')

# String substitution for every C/C++ file.

# As an example, hello.cpp turns into ./build/hello.cpp.o

OBJS := $(SRCS:%=$(BUILD_DIR)/%.o)

# String substitution (suffix version without %).

# As an example, ./build/hello.cpp.o turns into ./build/hello.cpp.d

DEPS := $(OBJS:.o=.d)

# Every folder in ./src will need to be passed to GCC so that it can find header files

INC_DIRS := $(shell find $(SRC_DIRS) -type d)

# Add a prefix to INC_DIRS. So moduleA would become -ImoduleA. GCC understands this -I flag

INC_FLAGS := $(addprefix -I,$(INC_DIRS))

# The -MMD and -MP flags together generate Makefiles for us!

# These files will have .d instead of .o as the output.

CPPFLAGS := $(INC_FLAGS) -MMD -MP

# The final build step.

$(BUILD_DIR)/$(TARGET_EXEC): $(OBJS)

$(CXX) $(OBJS) -o $@ $(LDFLAGS)

# Build step for C source

$(BUILD_DIR)/%.c.o: %.c

mkdir -p $(dir $@)

$(CC) $(CPPFLAGS) $(CFLAGS) -c $< -o $@

# Build step for C++ source

$(BUILD_DIR)/%.cpp.o: %.cpp

mkdir -p $(dir $@)

$(CXX) $(CPPFLAGS) $(CXXFLAGS) -c $< -o $@

.PHONY: clean

clean:

rm -r $(BUILD_DIR)

# Include the .d makefiles. The - at the front suppresses the errors of missing

# Makefiles. Initially, all the .d files will be missing, and we don't want those

# errors to show up.

-include $(DEPS)