文章目录

- 基础的文件操作

- 文件的系统调用接口

- 位图

- 向文件中写入

- 标记位选项总结:

- open的返回值

- 文件描述符fd

- fd==012与硬件的关系

- read && stat

- 重定向

- dup2

- 缓冲区的理解

- 经典的例子

基础的文件操作

引子:

#include <stdio.h>

int main()

{

FILE* fp = fopen("log.txt","w"); //打开文件

if(NULL == fp)

{

perror("fopen");

return 1;

}

fclose(fp); //关闭文件

return 0;

}

默认情况下,如果文件不存在,就创建了一个log.txt的文件

问题:创建文件的时候,只指定了文件名log.txt,系统怎么知道在pwd的路径下呢?

答:因为在运行文件操作的时候,已经变成了一个进程,默认结合进程所在路径。

我们要进行文件操作时,程序是跑起来的。文件打开和关闭,是CPU在执行我们的代码。

我们在windows创建一个新空文件,显示的0KB是内容为零,文件的属性(名字、创建时间等)是要在磁盘上占空间的

文件 = 属性 + 内容

在文件内部进行写入:(如果是往屏幕写入,stream==sdout)

#include <stdio.h>

int main()

{

FILE* fp = fopen("log.txt","w");

if(NULL == fp)

{

perror("fopen");

return 1;

}

fprintf(fp,"helloworld,%d,%s,%lf\n",10,"hello Linux",3.14);

fclose(fp);

return 0;

}

fopen函数中的w表示:

1.如果不存在,就在当前路径下,创建文件

2.默认打开文件的时候,就会先把目标清空

验证目标情况:把写文件和关闭文件注释掉

#include <stdio.h>

int main()

{

FILE* fp = fopen("log.txt","w");

if(NULL == fp)

{

perror("fopen");

return 1;

}

//fprintf(fp,"helloworld,%d,%s,%lf\n",10,"hello Linux",3.14);

//fclose(fp);

return 0;

}

35KB的内存变成了0KB

以a方式打开文件:追加(appending),不会清空文件

#include <stdio.h>

int main()

{

FILE* fp = fopen("log.txt","a");

if(NULL == fp)

{

perror("fopen");

return 1;

}

fprintf(fp,"helloworld,%d,%s,%lf\n",10,"hello Linux",3.14);

fclose(fp);

return 0;

}

上面两个操作跟输出重定向很像:把内容写入到log.txt文件中

echo "hello Linux" > log.txt

先清空再写入

所以重定向一定伴随着文件操作

可以直接用输出重定向创建文件(跟“w”功能一样)

其中>>是以"a"的方式打开

echo "hello Linux" >> log.txt

文件 -> 硬盘 ->外设 -> 硬件 -> 向文件中写入,本质是向硬件中写入 -> 用户没有权利直接写入 -> OS是硬件的管理者 -> 通过OS写入 ->

OS必须给我们提供系统调用接口(OS不相信任何人) -> fopen/fwrite/fread/fprintf/scanf/printf/cin/cout… -> 我们用的C/C++/…其他语言都是对系统调用接口的封装

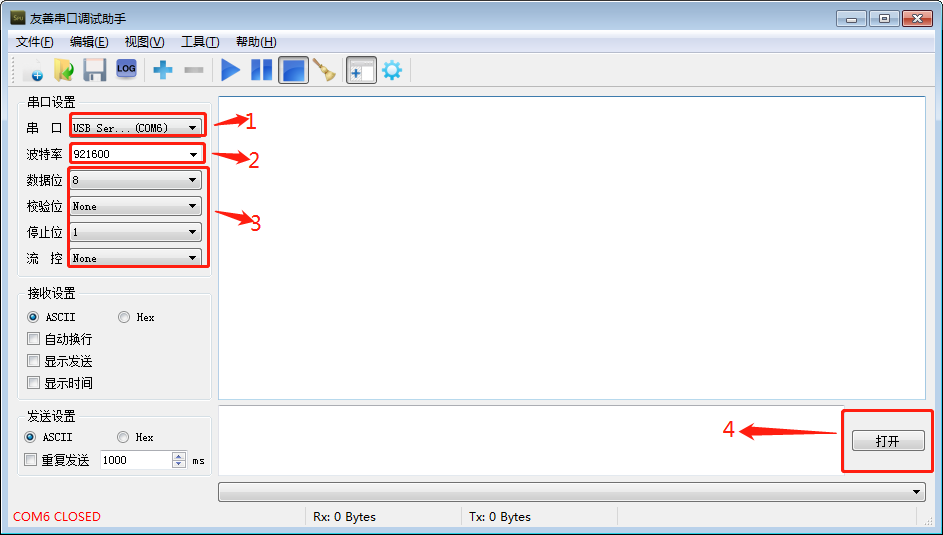

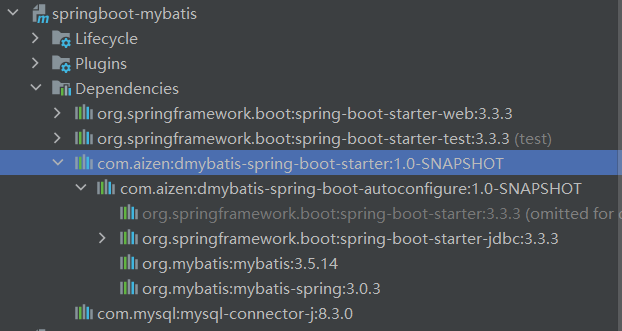

文件的系统调用接口

返回的是一个int ,被称为文件标识符,失败的话返回-1。查看返回值的信息/return val

先用看看效果:

O_WRONLY 表示只写 ;O_CREAT 表示没有log.txt就创建

#include <stdio.h>

#include <sys/types.h>

#include <sys/stat.h>

#include <fcntl.h>

int main()

{

// system call

int fp = open("log.txt",O_WRONLY | O_CREAT);

if(fp < 0)

{

perror("open");

return 1;

}

return 0;

}

创建是创建了,但发现权限有些不对,这个权限是个乱码

因为如果在Linux中新建一个文件,必须知道起始权限是什么!上面这段代码更多是操作已经被打开的文件

所以就有了第三个参数

这里涉及到了权限的相关知识 Linux权限中都有所描述

[sjl@hcss-ecs-1bcb 9_1]$ cat myfile.c

#include <stdio.h>

#include <sys/types.h>

#include <sys/stat.h>

#include <fcntl.h>

int main()

{

// system call

int fp = open("log.txt",O_WRONLY | O_CREAT,0666); //0666表示读写读写读写权限

if(fp < 0)

{

perror("open");

return 1;

}

return 0;

}

但是发现是读写读写读的权限 0664

因为umask权限掩码,他会去与你设定的权限进行一些运算

可以直接使用系统当中的umask

#include <stdio.h>

#include <sys/types.h>

#include <sys/stat.h>

#include <fcntl.h>

int main()

{

umask(0);

// system call

int fp = open("log.txt",O_WRONLY | O_CREAT,0666);

if(fp < 0)

{

perror("open");

return 1;

}

return 0;

}

权限就是 读写读写读写 0666

程序中的umask和系统中的umask,在程序中按照就近原则使用umask

位图

设计一个传递位图标记位的函数

#include <stdio.h>

#include <sys/types.h>

#include <sys/stat.h>

#include <fcntl.h>

#define ONE 1 // 1 0000 0001

#define TWO (1<<1) // 2 0000 0010

#define THREE (1<<2) // 3 0000 0100

#define FOUR (1<<3) // 4 0000 1000

void print(int flag)

{

if(flag&ONE)

printf("one\n"); //可以替换成其他功能

if(flag&TWO)

printf("two\n");

if(flag&THREE)

printf("three\n");

if(flag&FOUR)

printf("four\n");

}

int main()

{

print(TWO);

printf("\n");

print(ONE|TWO);

printf("\n");

print(ONE|TWO|THREE);

printf("\n");

print(ONE|FOUR);

printf("\n");

print(ONE|TWO|THREE|FOUR);

printf("\n");

return 0;

}

回到文件正文,open中的标记位有很多

O_RDONLY : 只读 ;O_WRONLY :只写 ;O_RDWR:读写

向文件中写入

C语言是fwrite接口,操作系统是write

#include <stdio.h>

#include <string.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#include <sys/types.h>

#include <sys/stat.h>

#include <fcntl.h>

int main()

{

umask(0);

// system call

int fp = open("log.txt",O_WRONLY | O_CREAT,0666);

if(fp < 0)

{

perror("open");

return 1;

}

const char* message = "hello Linux\n";

write(fp,message,strlen(message)); //\0是C语言,跟系统文件没关系,所以不用strlen(message)+1

return 0;

}

把写入的字符串改一改

const char* message = "520";

发现是没清空,直接写入

清空的选项O_TRUNC:如果文件已经存在并且是常规文件,并且 open 模式允许写入

下面这段代码叫做:写方式打开,不存在就创建,存在就先清空

int fp = open("log.txt",O_WRONLY | O_CREAT | O_TRUNC,0666);

追加写入就是O_APPEND

int fp = open("log.txt",O_WRONLY | O_CREAT | O_APPEND,0666);

标记位选项总结:

这三个常量,必须指定一个且只能指定一个

| O_RDONLY | 只读 |

|---|---|

| O_WRONLY | 只写 |

| O_RDWR | 读写 |

| O_CREAT | 若文件不存在,则创建它。需要使用mode选项,来指明新文件的访问权限 |

|---|---|

| O_TRUNC | 清空后写入 |

| O_APPEND | 追加写 |

open的返回值

先看现象

#include <stdio.h>

#include <string.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#include <sys/types.h>

#include <sys/stat.h>

#include <fcntl.h>

int main()

{

int fda = open("loga.txt",O_WRONLY | O_CREAT | O_TRUNC ,0666);

printf("fda:%d\n",fda);

int fdb = open("logb.txt",O_WRONLY | O_CREAT | O_TRUNC ,0666);

printf("fdb:%d\n",fdb);

int fdc = open("logc.txt",O_WRONLY | O_CREAT | O_TRUNC ,0666);

printf("fdc:%d\n",fdc);

int fdd = open("logd.txt",O_WRONLY | O_CREAT | O_TRUNC ,0666);

printf("fdd:%d\n",fdd);

return 0;

}

发现输出的是3,4,5,6 。没有0,1,2

因为进程默认会打开三个输出流,类型都是FILE*。

可以不用printf就能在显示器上打印

#include <stdio.h>

#include <string.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#include <sys/types.h>

#include <sys/stat.h>

#include <fcntl.h>

int main()

{

const char* message = "hello linux\n";

write(1,message,strlen(message));

return 0;

}

消息可以打印到显示器上

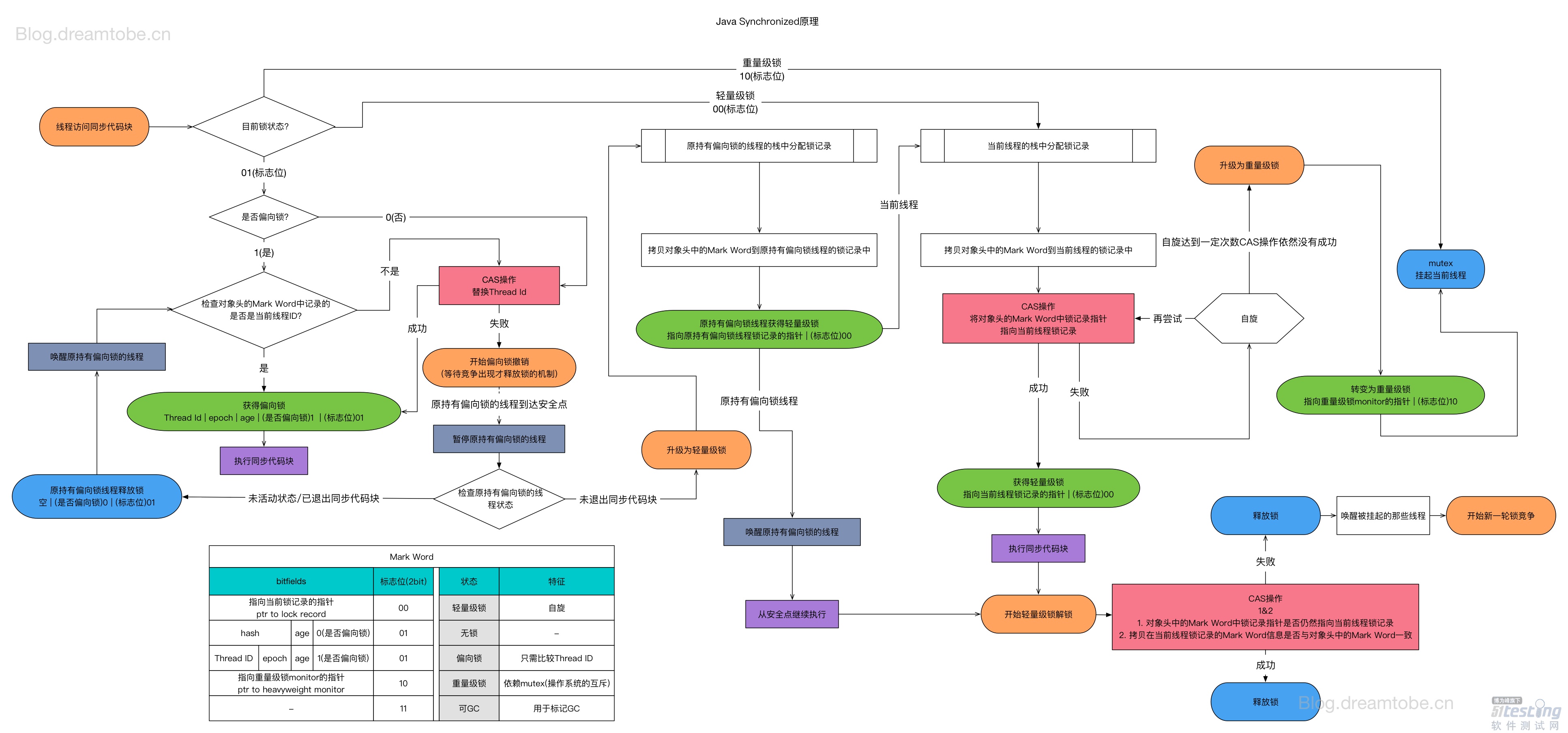

文件描述符fd

这样就可以把文件的管理起来

系统之中会存在很多的进程,也会存在很多的文件,进程与文件的数量比肯定是1:n的

进程task_struct中有struct files_struct* files指针,指向的结构体files_struct中有da_array[N]的指针数组,指向的是struct file文件

要找到一个文件的,进程只需要找到其文件的下标,返回个上层,上层拿着int fd就可以访问文件

综上所述: fd的本质就是:内核的进程:文件映射关系的数组的下标!

open的返回值就是拿到文件数组的下标

一旦把文件打开了:读写关都需要fd

读的本质是把文件内核级的缓存拷贝到应用层

如果文件内核级的缓存中没有数据,就会把进程阻塞,从磁盘中搬数据,搬完唤醒进程,再做拷贝

写数据也需要先把log.txt的内容,放入到文件的缓冲区,上层拷贝进缓冲区,在缓冲区更改内容,然后再由OS进行定期刷新到磁盘中

所以读写都是函数的一种拷贝

open在干什么呢?

1.创建file

2.开辟文件缓冲区的空间,加载文件数据(延后)

3.查进程的文件描述符表

4.file地址填入对应的表下表中

5.返回下标

源码:

进程task_struct中的files指针

struct files_struct中的数组

这个就是在struct file中打开的文件

内核级缓冲区

fd==012与硬件的关系

fd==0,1,2是默认打开的

那硬件如何和软件产生关系的?

要往每种的外设中读写数据,所以每种的外设有自己的读写方法

工程师肯定要写每种设备的驱动

每一个被打开的设备,OS肯定会为设备创建struct file,struct file中会包含函数指针

要访问一个struct file,直接从中调用read,就可以直接调用键盘的方法

从OS往上看,不用关心底层的差异。

在上层看到的所有的设备叫做一切皆文件

拿着同一种struct file可以访问各种设备:叫做多态

源码:这是struct file中的一个指针,他指向的是一个操作表

操作底层方法的指针表

这一层又叫做vfs全称叫做virtual file system(虚拟操作系统)

过一遍在文件中写入的过程:

open打开log.txt,在file_struct拿到log.txt的文件描述符3传到上层

write拿到fd,buf,长度的参数后写入到缓冲区中

后面由操作系统定期刷新到磁盘中

综上所述:操作系统只认文件描述符fd

如何理解C语言通过FILF*访问文件呢?

#include <stdio.h>

int main()

{

FILE* fp = fopen("log.txt","a");

if(NULL == fp)

{

perror("fopen");

return 1;

}

fprintf(fp,"helloworld,%d,%s,%lf\n",10,"hello Linux",3.14);

fclose(fp);

return 0;

}

首先fopen,fwrite…都是库函数

#include <stdio.h>

int main()

{

FILE* fp = fopen("log.txt","w");

if(fp == NULL) return 1;

printf("fd:%d\n",fp->_fileno); //fileno就是文件标识符

fwrite("hello",5,1,fp);

return 0;

}

也可以把stdout等的文件描述符打出来

#include <stdio.h>

int main()

{

printf("stdin:%d\n",stdin->_fileno);

printf("stdout:%d\n",stdout->_fileno);

printf("stderr:%d\n",stderr->_fileno);

return 0;

}

所有C语言上的文件操作函数,本质底层都是对系统调用的封装

C语言为什么这么做?

C语言如何做到跨平台性?

底层不一样,但在上层fopen,fwrite语法都一样的。

如果所有语言都想要有跨平台性,就要对不同的平台系统调用进行封装–>文件接口就有了差别

一个进程:默认会打开stdin,stdout,stderr,这里验证一下:

运行以下代码的时候,打开进程文件夹进行查看

ls /proc/pid

#include <stdio.h>

#include <unistd.h>

int main()

{

while(1)

{

printf("pid:%d\n",getpid());

}

return 0;

}

这里指向同一个地方是因为云服务器,并没有键盘等。

read && stat

这里介绍一个函数stat

文件 = 内容 + 属性

stat就是对文件属性做操作的

目前索要的就是st_size:文件有多少字节

返回值:如果成功返回0;错误返回-1

#include <stdio.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#include <string.h>

#include <sys/types.h>

#include <sys/stat.h>

#include <fcntl.h>

const char* filename = "log.txt";

int main()

{

struct stat st;

int n = stat(filename,&st);

if(n < 0) return 1;

printf("file size:%lu\n",st.st_size); //类型为无符号整型

int fd = open(filename,O_RDONLY);

if(fd < 0)

{

perror("open");

return 2;

}

printf("fd:%d\n",fd);

char* file_buffer = (char*)malloc(st.st_size+1); //多申请一个字节为了打印出来

n = read(fd,file_buffer,st.st_size);

if(n > 0)

{

file_buffer[n] = '\0'; //写文件的时候没有把\0写进去

printf("%s\n",file_buffer);

}

free(file_buffer);

close(fd);

return 0;

}

重定向

做个实验,先把文件fd==0关掉

#include <stdio.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#include <sys/types.h>

#include <sys/stat.h>

#include <fcntl.h>

const char* filename = "log.txt";

int main()

{

close(0);

int fd = open(filename,O_CREAT | O_WRONLY | O_TRUNC,0666);

if(fd < 0)

{

perror("open");

return 1;

}

printf("fd:%d\n",fd);

close(fd);

return 0;

}

发现新创建的文件fd==0

把1关掉

close(1);

发现并没有打印

文件描述符的分配规则:查自己的文件描述符表,分配最小的没有被使用的fd

再谈论一个实验:

#include <stdio.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#include <string.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <sys/types.h>

#include <sys/stat.h>

#include <fcntl.h>

const char* filename = "log.txt";

int main()

{

close(1); //关闭stdout

int fd = open(filename,O_CREAT | O_WRONLY | O_TRUNC,0666);

if(fd < 0)

{

perror("open");

return 1;

}

printf("printf,fd:%d\n",fd);

fprintf(stdout,"fprintf,fd:%d\n",fd);

fflush(stdout); //刷新缓冲区

close(fd);

return 0;

}

会发现并没有打印到显示器上,而是把内容放到log.txt中

把flush去掉,再次运行

#include <stdio.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#include <string.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <sys/types.h>

#include <sys/stat.h>

#include <fcntl.h>

const char* filename = "log.txt";

int main()

{

close(1); //关闭stdout

int fd = open(filename,O_CREAT | O_WRONLY | O_TRUNC,0666);

if(fd < 0)

{

perror("open");

return 1;

}

printf("printf,fd:%d\n",fd);

fprintf(stdout,"fprintf,fd:%d\n",fd);

close(fd);

return 0;

}

log.txt被创建出来了,但没有内容

综合上面两个现象谈一下原因:

先关闭fd== 1 ,不再指向stdout。然后log.txt被打开,被分配到了fd== 1 的位置上

printf和fprintf都是往stdout打印,只认stdout == 1 ,不管下层的变换

本来应该向屏幕打印的内容却打印到了log.txt中,这叫做重定向

重定向的本质:是在内核中改变文件描述符表特定下表的内容,与上层无关

关于fflush(stdout)不能写入log.txt的原因:

stdout的类型是struct FILE*,struct file内部有_fileno还有语言级别的文件缓冲区,先写入stdout的文件级别的缓冲区,后再由文件级别的缓冲区写入到内核级别的缓冲区

所以fflush(stdout)是通过文件描述符把文件级别的缓冲区中的内容写入到内核级别的缓冲区当中

在return的时候刷新到内核级缓冲区中,但close(fd)把文件关了,所以刷新不了了

关于有人说:“\n"不也是刷新到缓冲区吗!”\n"是到内核级别的缓冲区刷新到磁盘,不是文件缓冲区干的活。这段代码连内核级别都没进入,当然写入不进去

dup2

这里主要介绍dup2:本质是文件描述符下表的所对应的内容的拷贝

如果想要显示器打印 -> log.txt,是dup2(fd,1); oldfd -> newfd

把fd == 3的内容拷贝到fd ==1的下标中。

两个指针指向一个对象的问题:struct file中有个引用计数ref_count,记载了有多少指针指向自己。若没人指向自己,就释放掉了

验证:

#include <stdio.h>

#include <sys/stat.h>

#include <sys/types.h>

#include <fcntl.h>

#include <unistd.h>

const char* filename = "log.txt";

int main()

{

int fd = open(filename,O_WRONLY | O_CREAT | O_TRUNC,0666);

dup2(fd,1);

printf("hello world\n");

fprintf(stdout,"hello world\n");

return 0;

}

打印到log.txt文件中

把清空后写入变成追加写入就是追加重定向>>

#include <stdio.h>

#include <sys/stat.h>

#include <sys/types.h>

#include <fcntl.h>

#include <unistd.h>

const char* filename = "log.txt";

int main()

{

int fd = open(filename,O_CREAT | O_WRONLY | O_APPEND,0666);

dup2(fd,1);

printf("hello world\n");

fprintf(stdout,"hello world\n");

return 0;

}

缓冲区的理解

缓冲区就是一段内存空间。

缓冲区的优点:

1.解耦:把数据交给缓冲区,底层怎么做不用管

例子:你要送给远方朋友一个东西,去楼下找个快递点,把东西给到快递点,让快递小哥去送达。你只用负责把东西放到快递点以及填写资料即可。

2.提高效率:提高使用者的效率。提高IO刷新的效率(调用系统接口是有成本的,OS很忙,尽量要少调用).

例子:发快递都是攒到一起发,不能一个个发,因为发快递也是有成本的。

用户缓冲区的刷新策略:

1.立即刷新(无缓冲):C语言级的fflush(stdout) ; 系统级的fsync(int fd) 立即从内核缓冲区刷新到外设

2.行刷新:显示器(给用户看的,看的舒服)

3.全缓冲:普通文件:缓冲区写满,才刷新

4.特殊情况:进程退出,系统会自动刷新。

内核策略我们不关心,只要交给了操作系统,就相当于交给了外设

经典的例子

先看现象:

#include <stdio.h>

#include <string.h>

#include <unistd.h>

int main()

{

//C语言

printf("hello printf\n");

fprintf(stdout,"hello fprintf\n");

//system call

const char* msg = "hello write\n";

write(1,msg,strlen(msg));

return 0;

}

打印的也没错

加一个fork

#include <stdio.h>

#include <string.h>

#include <unistd.h>

int main()

{

printf("hello printf\n");

fprintf(stdout,"hello fprintf\n");

const char* msg = "hello write\n";

write(1,msg,strlen(msg));

fork();

return 0;

}

为什么打印到屏幕是打印了三行字符串,写入到log.txt是五行呢?

显示器文件->行刷新

./myfile

不经过内核缓冲区,在stdout里面待着等着被打印

向普通文件写入->全刷新(当缓冲区满了/进程退出才会刷新)

./myfile > log.txt

write是先刷新进内核里面了

printf/fprintf才刷新到stdout对应的缓冲区,并没有被写满

子进程和父进程运行完后,都要刷新各自的缓冲区,所以各自打印了两次。

看一下FILE*的源码中的缓冲区:

在/usr/include/stdio.h中

/usr/include/stdlib.h

![[Linux]:环境变量与进程地址空间](https://img-blog.csdnimg.cn/img_convert/1a5c9abd46ac7af93e5dbe7e0180b970.jpeg)

![[Git使用] 实战技巧](https://i-blog.csdnimg.cn/direct/19d8c77f77554a709f8ba383b96aa1e0.png)